Noah Berlatsky hits the nail on the head when describing a certain defensiveness with which the comics world has talked about the context in which the Charlie Hebdo massacre took place:

Since McKinney urges context, I should say that the context of his own remarks is clear enough. At least since Frederic Wertham pointed out that comics were often racist, sexist, violent, and kind of crappy, the comics community has been exceedingly sensitive to any criticism that calls into question the moral or social content of cartooning. On top of that, comics have long been seen as childish, largely aesthetically worthless pulp crap; comics scholars have waged a long, difficult campaign to get them recognized as complex artistic expression, worthy of study. McKinney, then, is not really trying to add nuance to the Charlie Hebdo discussions, which is why he adds none. He is instead repeating (under the validating mantle of scholarship) the same arguments that comics has used for decades to defend itself against hostile critics. To wit, comics are complicated and moral, and if you disagree, you’re a Puritan thug and a fool.

The thing is that Wertham and the other fifties critics of comics were right about the worthlessness of a lot of comics, the sexism, racism and crudeness that tainted a lot of the medium. Their mistake was that this was inherent to comics as a medium, rather than just a reflection of the societies these comics were published in. Wertham was a progressive critic, but his work was largely used and abused by conservatives and those who’d rather retard the medium to safeguard their profit than allow it to mature. This sordid history has saddled comics with an often justified persecution complex, making it hostile to anything and anybody wanting to look at wider societal concerns when criticising the medium.

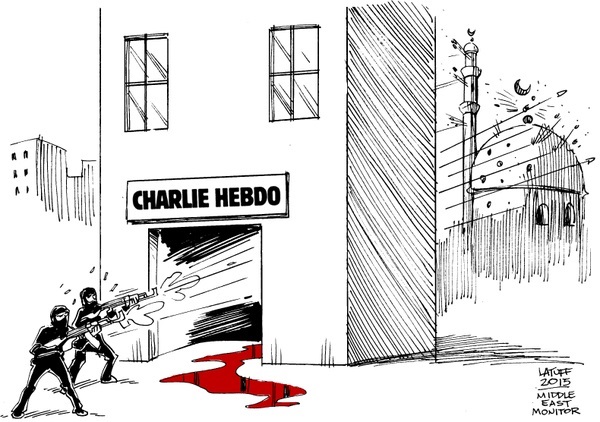

Not so much superheroes these days, when Islamophobic advertising is defaced with Ms Marvel cartoons and nobody bats an eye. It’s more the serious comics press that still has this problem and it’s come out the strongest in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo massacre as a) obviously nobody wants to sound even remotely like they blame the cartoonists for being murdered and b) all the old self defense reflexes come back to the surface. We also saw that during the original Mohammed cartoon saga back in 2004 when the coverage in the comics press revolved around the right of the cartoonists to draw what they wanted.

Which, to be honest, is not a bad first principle in the wake of organised terror or state suppression, but it does make it difficult to talk about the limits of cartoon satire and lampooning and where it shades into Islamophobia or racism. The temptation to believe that because they were murdered for their cartoons, that makes these cartoons retroactivily justified. Not something said in so many words perhaps, but I taste that in a lot of the coverage surrounding Charlie Hebdo, the desire to absolve the murder victims from any sin of racism or sexism, when of course that shouldn’t matter. Nobody believes that the victims were to blame for their own murders, especially since they appear to have been chosen to get the maximum publicity for their murderers, rather than because of the supposed offence they caused.

If we really believe comics are worthy of study, of being taken seriously, we need to be able to also study and criticise them in a broader context than just the artform, we need to be able to talk about what Charlie Hebdo did and didn’t do wrong, whether or not their satire of rightwing tropes actually shaded into using these same rightwing tropes and what their impact was, positive or negative. without shouting down discussion with freedom of speech. That’s a given.