Comix

The sad faith of the Big Two’s happy little cogs

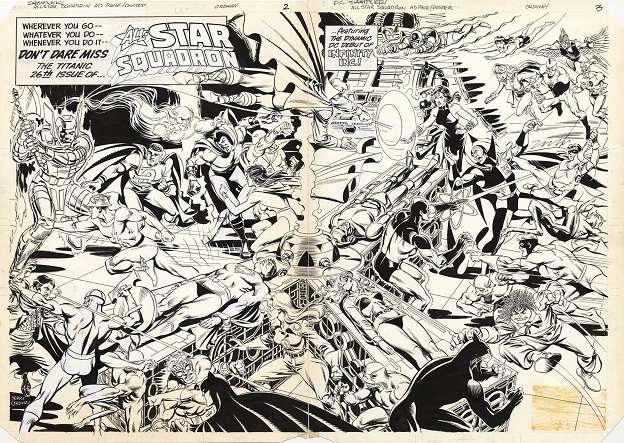

It’s hard to believe, but eighties and nineties DC Comics mainstay Jerry Ordway explains isn’t getting any work from them anymore and can’t live on the royalties for his older stuff:

On a recent Absolute Infinite Crisis hardcover, I had 30-odd pages reprinted in there, a book that retailed for over a hundred dollars– a book that DC never even gave me a copy of, and the royalty amounted to a few dollars, I couldn’t buy a pizza on that windfall. I want to work, I don’t want to be a nostalgia act, remembered only for what I did 20, 30 years ago.

In a way, Ordway is lucky. He at least still gets some royalties. Had he worked on Disney comics like Don Rosa, the most popular Donald Duck cartoonist after Carl Barks, he wouldn’t have received any royalty at all, as Rosa made clear in his explanation as to why he stopped drawing:

Disney comics have never been produced by the Disney company, but have always been created by freelance writers and artists working for licensed independent publishers, like Carl Barks working for Dell Comics, me working for Egmont, and hundreds of others working for numerous other Disney licensees. We are paid a flat rate per page by one publisher for whom we work directly. After that, no matter how many times that story is used by other Disney publishers around the world, no matter how many times the story is reprinted in other comics, album series, hardback books, special editions, etc., etc., no matter how well it sells, we never receive another cent for having created that work. That’s the system Carl Barks worked in and it’s the same system operating today.

For a time back in the eighties and early nineties it looked like (American) comics as a field would evolve beyond it’s low rent, exploitative roots and start treating its talent better. But that needed a growning, not a stagnating field and while comics have always been dying, never more so than in the past two decades. Working for the mainstream, commercial comics publishers in the US was always a good working class sort of career, where you could make decent money if you worked hard and were reliable, but were never going to get rich from. Nor would you get a pension from your work or anything other than a flat rate, but at least you’d still might be able to support yourself even after retirement with freelance work.

But when the slow collapse of the comics industry was accelerated with the mid-nineties crash, when the speculators and collectors left the field and superhero comics became what it was always destined to be, a niche market, it meant there were far too many cartoonists for the field to sustain and all the old pros, some having worked decades for the same company, would gradually disappear, retire, retrain, the lucky ones doing reproductions or sketches at comics cons to get some money, but many of them, like Jerry Ordway, finding it harder to make a living from what once seemed a safe job.

In some ways then what’s has happened to the commercial comics industry is a belated echo of what happened to so many American industries no longer needed or done cheaper elsewhere. These days there is still a comics industry, but outside the rotting corpses of the socalled Big Two it’s a much more boutique approach, one aimed at a smaller audience willing to pay more for a particular cartoonist’s vision or for excellently curated collections of the best of American comics history, with little room for those professionals for which comics was always more of a vocation than a personal calling. There’s no call for assembly line workers when you’re building cars by hand.

Comics as their own thing (Campbell was right)

As a kind of bible of pure comedy, the early Mad falls remarkably short of perfection however influential. Where is the personal slander, the rambunctious sex, the mad philandering, the sublime depravity and the political skewering we expect of the richest sources of comedy? Over two millennia ago, Aristophanes was brilliantly mocking the tragedies of Euripides (Women at the Thesmophoria) and risking prosecution with forthright attacks on the leaders of Athens. Contrast this with what we get in Mad. In place of Aristophanes’ unrestrained invective, Shakespeare’s poetic discursions on self-delusion, Wilde’s acute observations of social norms, and Monty Python’s Dada flavored madness we get parodies of superheroes and pulp characters.

It’s somewhat ironic that Ng Suat Tong uses such high-Grothian criticism to put the boot into EC Comics, one of Gary Groth few sacred cows. Groth might have also invoked Aristophanes to skewer some quickly forgotten piece of pseudo art, some DC or Marvel pretense at doing literary superhero comics. There’s something very Pseuds Corner about this litany of unassailable comedic, literary giants being called to the stand in the case against EC Comics, as silly as Stan Lee calling on the shades of Michelangelo and Shakespeare (again) in defence of comics in one old Bullpen Bulletin column.

I like Chris Mautner’s summarisation of Ng Suat Tong’s position better:

In an essay that ran in issue #250 of The Comics Journal – and was recently republished on the Hooded Utilitarian website – the critic Ng Suat Tong took to task one of the comics’ most sacred cows, EC. In the essay, entitled EC Comics and the Chimera of Memory, Suat argues that nostalgia has blinded critics and readers to EC’s many faults; that while the house that Bill Gaines built might have influenced many and laid the groundwork for the underground era, the stories themselves rarely deserve the lofty reputation they have attained.

To which Gary Groth of course had to respond:

In the impoverished cultural context of comics publishing at the time, the EC line was an astonishing achievement; Gaines’s EC came as close as a mainstream comics publisher could to being the comics equivalent of Barney Rossett’s Grove Press. What other comics publisher would even think of adapting stories from the Saturday Evening Post, use stories by Guy de Maupassant, or steal from the best — Ray Bradbury?

Which, compared to Ng Suat Tong’s list comes off decidedly middlebrow. What’s significant though is, that again these are all literary examples, with art not getting a look in. Both miss Eddie Campbell’s point, in his “literaries” essay:

Writing comics is a special skill quite different from writing prose. But before you take it all apart, ask: can you take the pictures out of a sports cartoon, or reduce a clown’s circus performance to its plot? Can everything about a musical performance be conveyed in a stave of notes, or can everything about a film be known from its shooting script? Sometimes, while everybody else was watching the clock, the clown, the actor, the singer, the cartoonist, the writer even, because writers never have as much freedom as we think they have, have slipped their own story in between the tick and the tock.

You can’t judge comics by their writing, their plots alone, you can’t separate the art and writing that easily and judge either in isolation. What makes comics art is not the writing or the art, it’s both as whole. As everybody quoted here does, we’re still judging comics too much in terms of other media, in how well it lives up to our expectations of literay worth, or how well it resembles film, but we rarely look at comics holestically and as their own thing.

It doesn’t really matter whether or not EC Comics was entirely as good and revolutionary as mainstream comics history has it, or whether it was as overrated as Ng Suat Tong would have it: what matters is that it hasn’t been appreciated and critically evaluated in terms of its own thing, but always in terms of other media.

Rich Johnston, you ignorant slut

DC Comics hire Orson Scott Card, science fiction author and noted homophobe, to write some Superman stories. People not surprisingly object. Bleeding Cool mudracker Rich Johnston comments and feels the need to warn people about the evils of censorship:

Some try to draw a line between an opinionated person and an activist. I disagree, any famous person who expresses an opinion, especially in this day and age, de facto becomes an activist for that opinion.

It’s a very dangerous game, it has led in the past to witchtrials, McCarthyite or otherwise, and it’s no better than the actions of, say, One Million Moms. And next time? It could be you…

This is the sort of naive fear people who don’t pay enough attention to history and politics have, from vaguely remembered civics classes and decades of middle of the road propaganda about how all kinds of extremism are equally bad, the sort of semi-liberal idea that goals don’t matter, but methods do. Which leads to such absurdities as saying that taking action against bigotry is as bad as the bigotry itself, as notable dimwit Mark Millar has done. Of course if you follow this logic to the bitter end, not only could you never boycott writers or artists for being bigots, you should actually be obliged to buy their comics, or you’re punishing them for their opinions.

But of course there’s a huge difference between those McCarthyite showtrials Johnston is so worried about and grassroots boycott campaigns. McCarthy operated with the full support of the state and most of the press against people who actually were a danger to the United States, to further his own career, destroying the lives of those he persecuted. Orson Scott Card meanwhile is a successful writer with a long career who never had to suffer for his bigotry, who will still be rich and successful even if he never gets to write Superman.

What’s more, it’s not his speech that people object to, nasty though his opinions about homosexuality are, but the fact that he is actually on the board of directors of the National Organization for Marriage, which works hard to keep homosexual people second class citizens in America. It’s somewhat disingenuous of Johnston to ignore this and pretend he’s just some ordinary person with unfortunate opinions, as harmless as your racist nan.

Can you let somebody like that write for Superman, symbol of Truth, Justice and the American Way, who used to take on the Klan in his radio adventures? Really?

Joost Swarte

Cartoonist:

Ilustrator:

Architect:

Designer:

Allround renaissance man:

Blues singer?