Comix

Why talk about race in comics?

David Brothers talks about why he writes about comics and race:

Why do I write about race? Partly because other people are so terrible or inept at recognizing the impact of race on their life, let alone actually talking about it. When I first started, it was a lark. Then I thought I could convince Marvel and DC to do something other than pander to their audience. Then I realized that was stupid, and I’d be better off just talking about this stuff. I’ll spit hollowpoints at them them when they miss, praise them when they hit, and hopefully someone who reads me will look and go, “Oh, this makes sense” and tomorrow will be a little better.

It took me forever to come to that point, though. I figure it’s obvious if you read my posts from that first Black History salvo on through today. Maybe not. Maybe I’m the only one that pays that much attention to what I do. But I have changed and grown as a result of talking about race and comics.

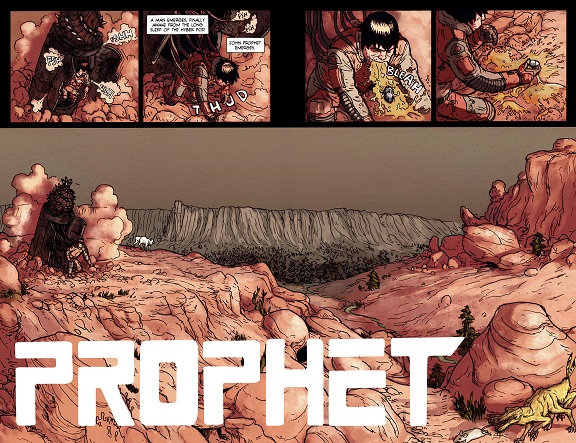

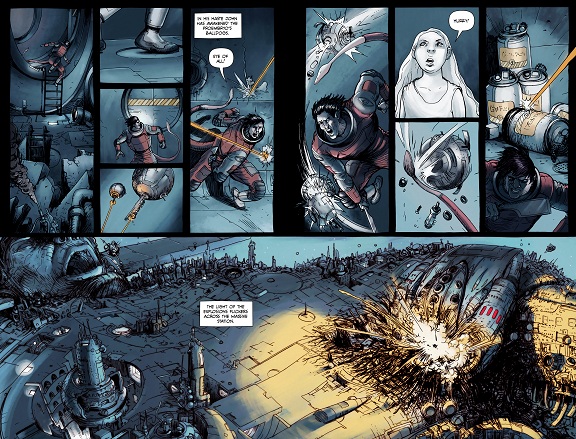

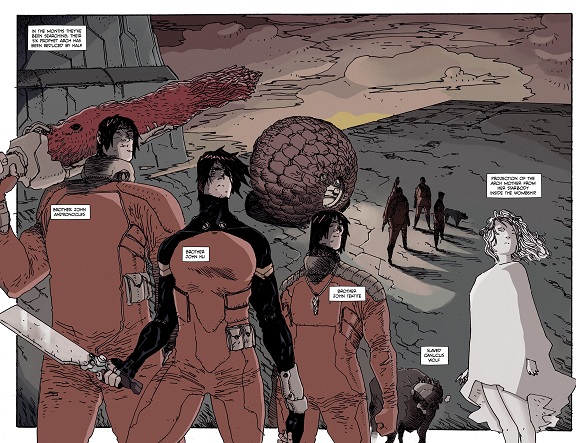

Prophet — Brandon Graham et all

That Rob Liefeld, back at Image and having somewhat rehabilitated himself this past decade, would attempt to restart his old nineties titles was expected. That he even would get back to Prophet wasn’t much of a suprise either, but that the new Prophet would become a cult success and a critical hit, that I never suspected. I don’t really remember the original Prophet, just another of Liefeld’s Cable clones, akk hip pouches and big guns, that got his fifteen minutes of fame thanks to Wizard hype with nothing to distinguish it from the dozens of other Liefeldian creations published back then.

The second time around Prophet has nothing of Liefeld in it anymore, with the only thing surviving from the original series being the title and John Prophet’s general appearance, sans hip pouches. Apart from that nothing connects the two series.

I don’t know the people behind the new series: Brandon Graham, the main writer and Simon Roy, Farel Dalrympie, Giannis Milonogiannis, the artists, with Brandon also lending a hand to the art for one chapter. Never heard of them before this, never read anything they’ve done, all I know is one thing. Somebody must’ve read a lot of French seventies science fiction comics.

It’s the art that you notice this first. It’s rare for artists working in American comics to be this influenced by European art rather than Japanese manga, especially in a science fiction series like this, but the names that come up to compare with are people like Enki Bilal, Philippe Druillet, Paul Gillon, J. C. Mezieres, Jean Claude Forest, and of course Moebius.The designs of the aliens, the vehicles, the flora and fauna of the far future Earth, the slightly trippy setting and matter of fact protagonist, it could’ve been a serial in mid-seventies Métal Hurlant.

The story too is very Métal Hurlant like: Prophet awakes in an underground pod, on a far future Earth unfamiliar to him, a voice in his head urging him to travel East. The country he travels through is devoid of familiar live, taken over by various aliens, bearing the scars of long ago wars. Over the course of the first three chapters it turns out Prophet’s task is to restore the Earth Empire by activating the G.O.D. satellite. His task complete, we learn that he is but one of a legion of clone brothers, as John Prophets all over the galaxy awaken and the action shifts elsewhere.

In all, I’ve no idea how these people got their seventies French sci-fi romp wedged into a nineties Image superhero title, or why, but I’m glad they did. This is a brilliant, original series like nothing else being published and while I keep harping on about how much it reminds me of something like Exterminator 17 e.g., the thing is that this is not an exercise in nostalgia, but something modern, something new, something that hasn’t really been done before. This is actually a series you may want to read as it comes out, rather than wait for the trades.

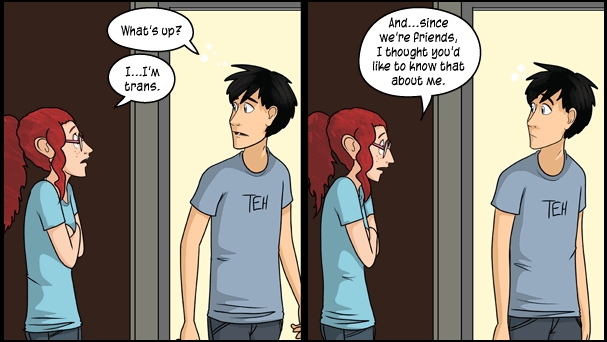

An unexpected revelation

Claire is a new character in Questionable Content, introduced some months ago as a co-worker of the (allegedly) main character Marten (on the right). I like the matter of fact way Jeph Jacques has introduced her being trans here. There had been no clues in earlier strips and no drama is made out of it; no big dramatic soap opera reveal is made here. If there’s any cartoonist I’d trust to handle this well it’s Jeph Jacques, looking forward to what he does with this.

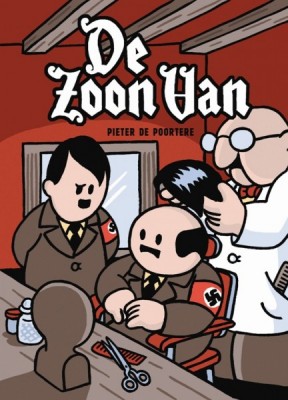

Translate this: Boerke – de Zoon Van

Translate this is an occasional series about European comics that need to be translated into English, inspired by Grant Goggins’ old Reprint This blog. Last time around it was Bernard Prince, this time it’s Boerke: De Zoon Van.

Boerke has actually been translated before; two volumes of Dickie have been published by Bries. However the Dutch language series runs to seven albums in total, of which De Zoon Van is the sixth. Translating the series shouldn’t be the hardest of jobs; the strips are mostly textless. Silent comics are perhaps the purest form of comics and Pieter de Poortere is very good at them. He manages to put a lot of character and emotion in his Playmobil like characters.

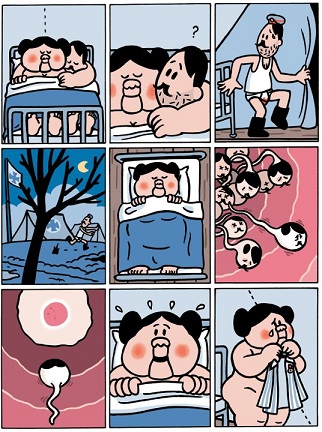

Whereas the first five or so albums are largely one page gag strips, this one is a complete story, the first longer story Pieter de Poortere has attempted for Boerke. As you might deduce from the cover, left, the story revolves around a certain German Chaplin moustache wearing dictator. Or rather, his son. Because it turns out that at the end of the First World War Hitler got slightly too friendly with a Flemish peasant woman and got himself a bastard son he never knew about: Boerke.

Boerke has to deal with all the little problems living in occupied Belgium in the Second world War brings with it: being mistaken for a collaborator, hiding a Jewish refugee and later an American airman, handing them over to the nazis when they fall in love and he gets jealous, try to commit suicide only to be almost hanged by the resistance, escaping, being mistaken for a jew and shipped to Auschwitz, that sort of thing.

Meanwhile in Berlin things are not going well either as Eva wants a child but Adolf, well, can’t get it up. She then tells him of the existence of his son, he goes to get him, some more adventures later they are united for the first time and the reich has a new slogan: Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Zwei Fuhrers…

There’s a strange sort of innocence about Boerke, helped by the simple, almost childlike artwork of de Poortere. The humour is black, but not cynical, if that makes any sense. The artwork is simplified but great, especially in the two page Where’s Wally spreads that intersperse the story.