Power Girl: A New Beginning — Justin Gray, Jimmy Palmiotti (writers), Amanda Conner (art)

As a character, Power Girl was always something of a joke. First introduced in the seventies as a young, militant “feminist” character by Gerry Conway to spice up his Justice Society series in All-Star Comics as Earth-2 Superman’s cousin, a copy of a copy (Supergirl). It didn’t help that the then artist on the series, Wally Wood, allegedly had a bet to make her breasts bigger each issue until somebody noticed — and nobody did. Once the series was cancelled, she did the guest star routine, showing up with the Justice Society or on her own, got her own not very interesting mini series in the mid-eighties, a new origin courtesy of Crisis on Infinite Earths doing away with Earth-2, then finally a regular spot on Justice League Europe as the house nag, where it was also revealed she had a bit of a personality disorder due to drinking too much diet cola.

All of this started to change with the Geoff Johns’ Justice Society series, where she got a bit more respect, but it still wouldn’t fill you with much hope that any regular Powergirl series would be any good. But it was.

I got the trade paperback of the first six issues cheap because I’d heard good things about the series and it was indeed much better than I would’ve expected. Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray wrote a perfectly nice, decent Bronze Age superhero series with stories that are actually dealt with in two-three issues, a few slowly developing subplots, even some attention to Powergirl’s private life, something that never was developed much before. There are some decent fights, good villains and they write with a bit of humour and in all do a not too shabby job.

But the real star of the series however is the artist, Amanda Connor. It’s always been the case that bad art can sink good writing much more easily than bad writing can sink good art and what we have here is excellent art uplifting a decent series into something much better. Connor’s art style is semi-realistic, slightly cartoony when needed, rather than the stilted realism that’s in vogue for superhero comics this past decade. The colouring, by Paul Mounts, reinforces this as it’s bright and poppy, not so muddy-brownish as seems to be the norm now, with Kara/Karen/Power Girl the brightest thing in the comic.

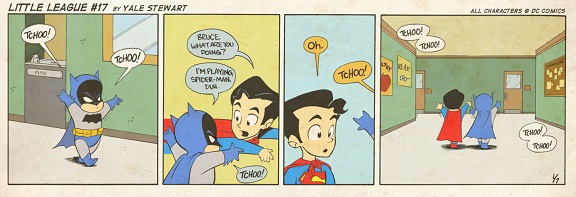

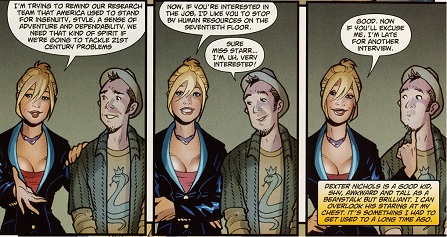

Connor is an accomplished artist, doing her fight scenes very well, but where she really shines is in the quieter scenes, the character building scenes like the one above, which really didn’t need the caption box to explain what’s happening there. The faces, the hand gestures, all feel perfectly natural and right, though they’re obviously somewhat exaggerated for effect. This is on even better display in the page shown below.

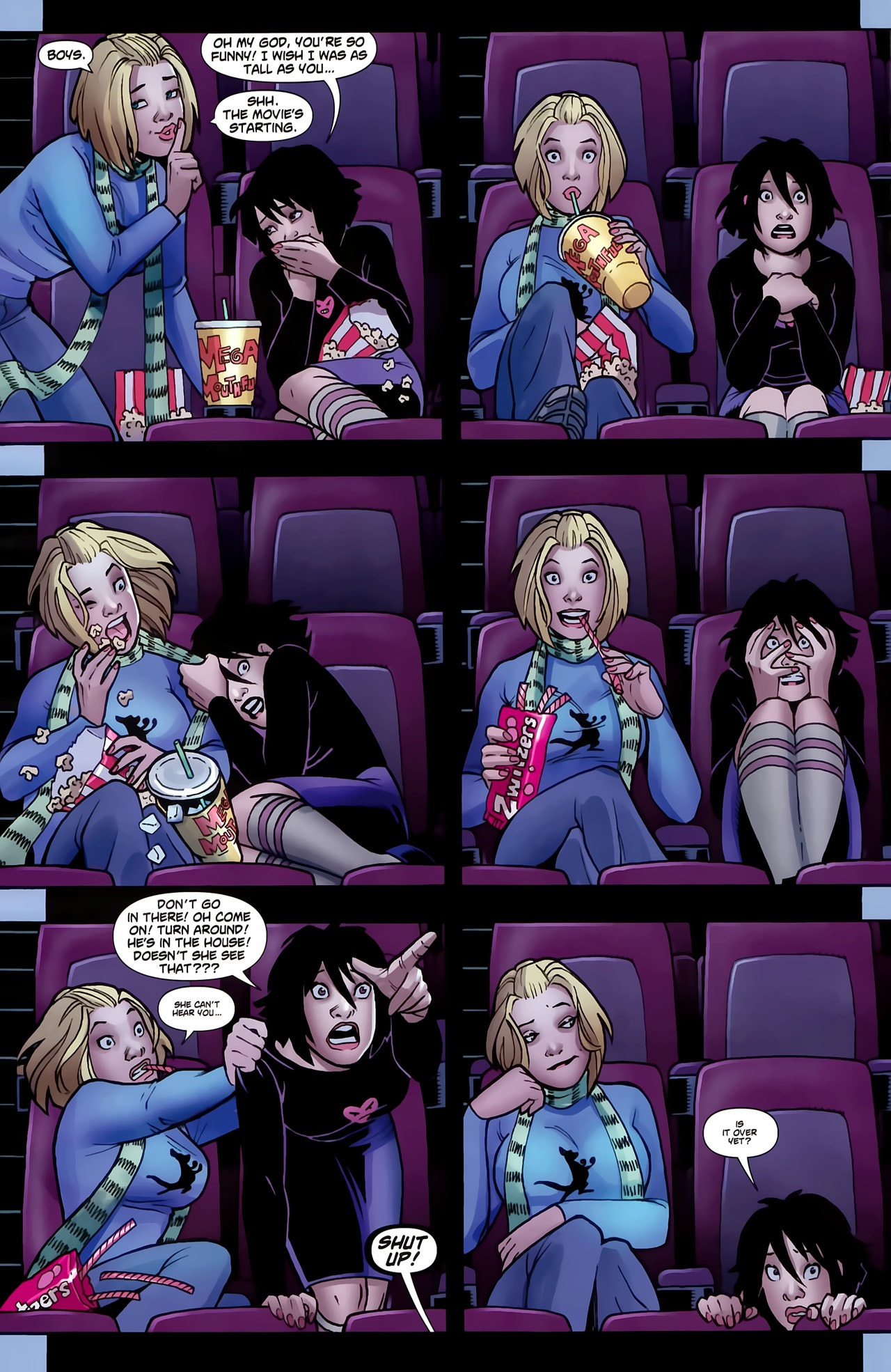

It’s just a page of Power Girl and her friend/fellow superheroine Terra enjoying a movie, but I love the acting and the facial expressions on both of them. But I also like the dress sense Connor has, as what both are wearing fits their characters and backgrounds. They’re clothes you could actual women wearing, not sexytimes comics clothing. Which is the best part of Connor’s art of course: no porn faces, no moronic fan service or broken spine crotch shots. Power Girl’s breasts are still there, are part of her, but no longer the whole of her and she actually wears clothing that doesn’t always draw attention to them.

It’s a shame the series never quite got the audience it deserved and what with the New DC and it’s focus on just the sort of moronic pandering this series didn’t lower itself too, it’s unlikely we’ll soon get a new Power Girl series even half as good as this one.