Tim O’Neil explains the real reason for the NuDC:

The post-Flashpoint DC Universe was created as a means of streamlining the company’s staggeringly diverse array of IP into forms more easily amenable to bookstore channels and especially digital distribution services. The goal – successfully achieved so far – has been to make DC resemble something less than an eclectically diverse publishing line and something more along the lines of a streamlined television network.

Given that, its not hard to see that many of the more controversial creative decisions have been made with an eye towards developing a ruthlessly efficient commercial applicability. Hence the explicit T&A books, hence the multiple attempts to ape existing popular Young Adult book franchises (you should be able to spot them yourself with no trouble), hence the multiple attempts to reframe existing properties as potential basic cable drama programming. The goal is to create stories that can be easily packaged and sold by genre to casual readers using digital devices whose size and visual capabilities have now synched up almost completely with the technical demands of displaying comic books.

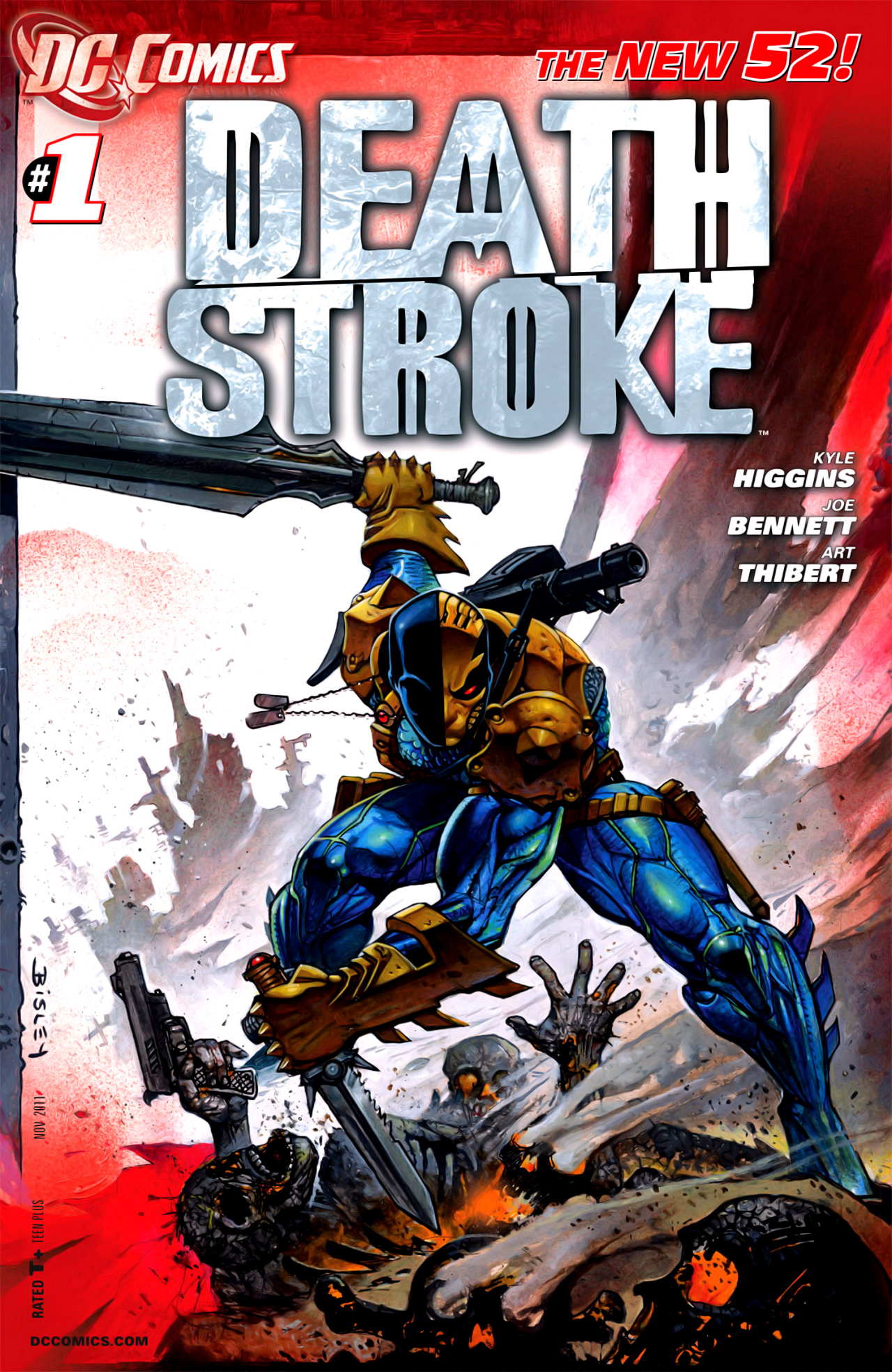

Though I think he’s got a point, I think it may be too much honour to assume that DC was this calculated about the reboot. The end product is just not good enough. Seen as a whole, the NuDC line is actually not commercial enough, not even half as cleverly exploitative as it could’ve been. There are the various continuity carry-overs Tim mentioned, like the Batman and Green Lantern titles which just continue to do what they would’ve done without the reboot, there are also a couple of titles, like e.g. Static Shock or Resurrection Man where you suspect somebody is using the reboot as an excuse to bring back an old favourite, or to get some offbeat new concept approved (Justice League Dark, Demon Knights), not to mention te series that are basically duplicates of each other (Deathstroke, Grifter or Blackhawks and Men of War). In sort, it’s all a bit of a mess if you want to believe in Tim O’Neil’s hypothese.

Where he is probably right is in the motivation behind the reboot, to make it more easier to stripmine the DC universe for new succesful media properties as motivated by the success Marvel has had in the past decade doing the same to their universe. Ironically, as with the original Crisis on Infinite Earths, published out of a desire to streamline the then existing DC universe to make it easier to lure Marvel readers because people who read the Claremont X-Men would’ve had trouble with the complicated concept of multiple earths, they once again got it arse backwards. Marvel has been succesful with its movies by being smart about picking the best parts of a decades long publishing history for their titles and not worry too much about if they mirror proper continuity. These films then naturally filter back into the original comics, but that’s just a side effect. It’s not necessary, as DC’s own successes with the various animated Batman series have shown.

But the powers that be at DC must’ve thought otherwise and put through this halfbaked revamp, which basically amounted to Wildstormising the DC universe. You got your asshole heroes not that different from the villains, lots and lots of shadowy governmenty conspiracies (who should be tripping over each other so many there are), gratitious sex (well, almost nudity) and “hey kids comics” violence, plots that don’t make no sense, both because they all seem have to start in the damn middle and because they all feature off brand characters who can’t care about yet because we don’t know them. It’s not a new development of course, DC has been moving in this direction for years, but with the reboot it’s become official.

It’s all not very good, not really thought out well and as original as a not very original thing, another dip in the well of failed ideas, but if it makes DC happy. Just don’t expect me to like it.