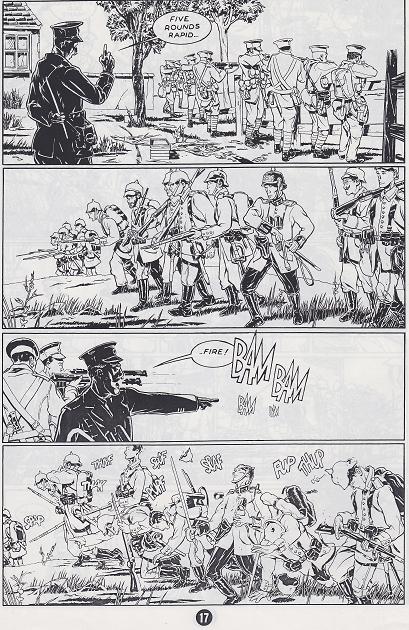

I’ve been to my parent’s place this weekend, to celebrate the birthdays of my sister and her partner who live nearby. As always a home visit is also an excuse to rescue some more of the vast collection of comics I’ve left behind there in storage. Amongst the gems I dragged away this time was an A4 sized, self published (?) comic called Rapid Fire: Terrible Sunrise Part Two, written and drawn by one Stan Martin. I known nothing more about it or its creator than what I could gleam from the comic itself when I bought it at Spacecaption 1999, a small Oxford comics convention. That’s one of the joys of going to cons, finding interesting looking small press or self published (“amateur”) comics done by people with no expectation — or even desire– to become professional cartoonists, but who draw comics just for the love of them. In this case I was drawn in by the subject matter, a battle set in the first days of World War I, as the forces of the British Expeditionary Force first come into contact with the vanguard of the German advance. Martin’s artwork, realistic, clear and with a hint of Ligne Claire in it also helped.

Rapid Fire depicts the battle between the North West Rifle regiment on the 23rd of August 1914 alongst the Mons-Condé Canal in Belgium and the advancing German forces of von Kluck. This wasn’t trench warfare, the front was still dynamic as the Germans were still pressing towards the Channel, trying to move around the defending English and French forces, who in turn were slowly retreating out of Belgium back into France. This was the last stand of the old professional British Army that had fought the colonial wars of the 19th century, opposing a modern conscription army much much bigger than them. As Martin puts it on the back cover:

The Kaiser’s army, of almost three million ferociously disciplined men, floods the farmlands of northern France. They attempt to crush the French before their Russian allies can mobilise to threaten Germany’s eastern border. The British Expeditionary Force barely figure in the Prussian plan to dominate the continent; two hundred and fifty thousand strong they are outnumbered more than five to one. The British soldier, however, is the most highly trained, best equipped in the world. In sixty seconds, armed with his short magazine bolt action Lee Engfield rifle he is capable of firing up to fifteen well-aimed rounds.

This is known as “the mad minute”.

Which also tells you that this is a war story, not an antiwar story, as we’re mostly used to when the First World War is brought up in fiction. Martin neither moralises about war nor glorifies the battle he depicts. His treatment is almost antiseptical, no sensationalist displays of gore, just men falling down with a “fup” or “thup”. This might seem old fashioned or a bit suspect, but it works well here; Martin trust his readers to know that war isn’t nice, he doesn’t have to rub it in nor has he any desire to. It’s an intellectualised view of battle, somewhat distancing you from it. The artwork helps with this. Even in action his figures look posed and stiff. The clean lines too help keep you detached from the story. He has a good eye for detail, but doesn’t go overboard with it.

I’ve never found another comic by Martin, nor much about him on the internet, save for one review of Rapid Fire, which coincidently uses the same page I scanned as well as an illustration. I’ve no idea if he has done more comics than this, but I hope so.