Tom Spurgeon is disappointed no comics creators were present in a NYT article about Edward Gorey:

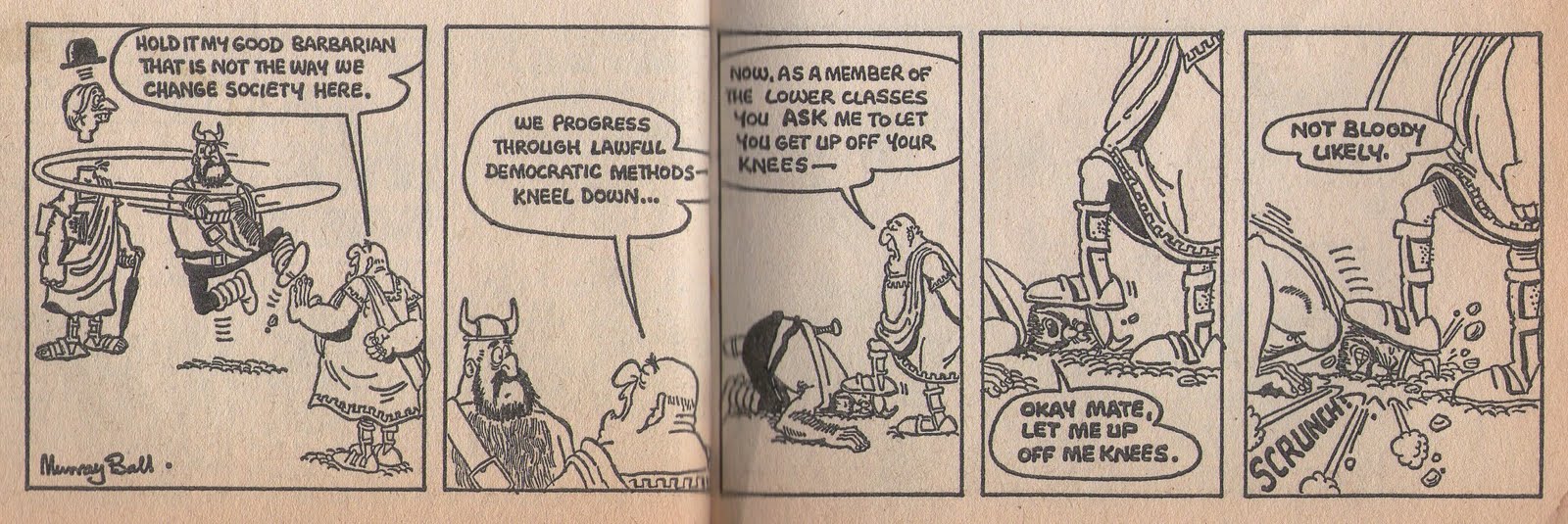

That’s what it seems like reading this New York Times profile of Edward Gorey, anyway, as authors and designers line up to claim his influence, without a cartoonist in sight. I’ve said this before, but it intrigues me that someone whose major works embody both the Scott McCloud (sequential narrative) and RC Harvey (verbal/visual blend) definitions of comics gets so little mention by and, actually, seems to have little direct influence within, the medium in which he seems to have worked.

I wonder if this is an example of comics not claiming its own, or more a case of the NYT not letting cartoonists in to the party. Neil Gaiman is quoted, but only as the author of Coraline, not for his comics work, which has its Gorey influences as well. More generally, with a respectable cartoonist like Gorey, there is as much a tendency for the wider art world to seperate him from his comics context is as there sometimes is for the comics world to disown him. It’s a pattern we’ve seen time and again, with people like Gorey, Al Hirschfeld or Charles Addams, or even Art Spiegelman with Maus.

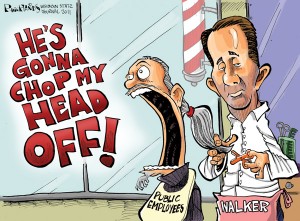

Obsolete ideas about high brow art versus low brow commercial product still determines the framework in which we think about comics and individual cartoonists. From a comics theory point of view whether a cartoonist’s work is published in in the New Yorker or Action Comics might not matter, but in practise it does reflect on how people percieve him: as a caricaturist/social commentator working in a highly respected tradition of satirical drawing dating back to at least the 18th century or as just another hack doing work for a medium held in contempt almost from its inception. Consciously or unconsciously, this sort of consideration will have helped shaped that NYT profile. Because Gorey was published in respectable, high art venues, the sort of people that will be asked to provide quotes for this profile will be novelists and film makers rather than cartoonists.

At the same time, with creators that do manage to break out of the comics ghetto something more insidious happens. From Spiegelman onwards, what you see is that their work is decontextualised, treated as a singular occurrence rather than as a work of art which is part of a wider tradition. Again, this is not necessarily done consciously, but just part and parcel to the way in which the respectable media ignore the low rent comic book. That usually, something like Maus or Fun Home is respected more for its subject matter than its strengths as a comic.