Tom Spurgeon is dissappointed in an interview with Wizard head honcho Gareb Shamus and takes issue with Shamus’ view of why people hated it:

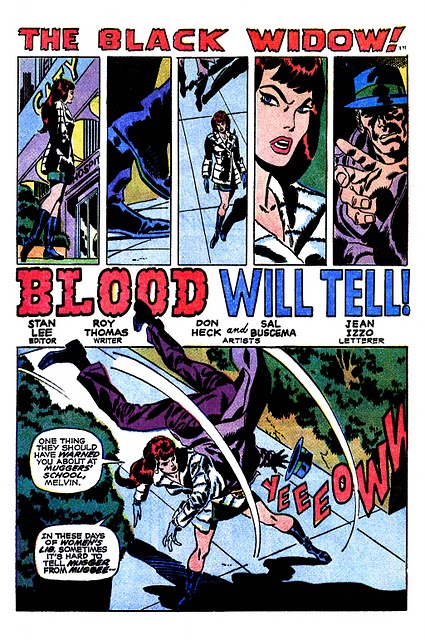

I don’t remember anyone criticizing Wizard during its initial years of publication because they preferred backwards-looking magazines. They were suspicious of the price guide and generally critical of the relentless hype and limited view of comics involved. Some were further disappointed by the general lack of an animating principle beyond celebrating the most popular superhero comic books of the day, feeding and feeding from that passionate fan base.

Also, it was kinda shit.

When Wizard came out I wasn’t really a sophisticated buyer of comics — I actually bought Youngblood #1 and #2 and #3 fresh from the stands — and the main magazine I used to buy was Comics Scene. Remember that? Glossy magazine done by the same people as who did Fangoria, half of each issue being about comics, half about animation and Hollywood movies based on comics or cartoons, somewhat shallow, with interviews in that weird format where the questions have all been left out and the answers edited to form one coherent story, actually available on newsstands as well as in comics shops. Forget The Comics Journal, that was my main fix for comics news and what I compared Wizard to when it first appeared. It looked interesting and kewl that first issue, but there was no “there” there. What I got instead was a whole generation of artists and writers learned to speak P.R., answer dumb questions and plug whatever shit they were selling that month. Alongside that you got various filler features: casting calls for movies that would never be made, hot or not lists and such, offering a few seconds of amusement better suited to bullshit sessions at yer local comics shop.

But if Wizard had only wanted to be the Entertainment Weekly for comics geeks, that would’ve been harmless. Pointless, but harmless. The real evil it did was with its bloody price guide, which kept the punters coming back each month by promising them that their month-old copies of Darkhawk were now worth serious money. The comics industry didn’t need any help setting up a destructive boom and bust cycle, but Wizard was still there to push it off the cliffs. A lot of players helped to almost destroy the American comics industry in the early to mid nineties, from the Big Two and Image and all the smaller publishers inspired to do gimmick covers, to the distributors attempting to gain a monopoly (and do not think Capital would’ve been better), to the shitheap comics shop ripping their customers off by selling new comics at inflated prices, the artists and writers willing to suck to be cool, to the suckers buying comics themselves, seriously thinking a comic with a print run in the millions will ever be worth more than its value in paper when there were perhaps a 100,000, maybe 200,000 proper comics readers in the US in the first place. But Wizard turned that self destructive tendency up to eleven, by basically lying to its readers about the money their comics were worth. It led people to believe their Valiant comics would fund their retirement and when inevitably, even the slower readers knew otherwise, bang went the comics market. It still hasn’t recovered.

So it’s not that “we like the comic creators from the past, how could you be writing about these new comic creators like Jim Lee, and Todd McFarlane, and Rob Liefeld”, but that a) everything in the magazine was shit, purile enhtertainment that actively kills brain cells while playing on people’s greed by telling them the worst comics ever written would be worth big big money in just a few months.