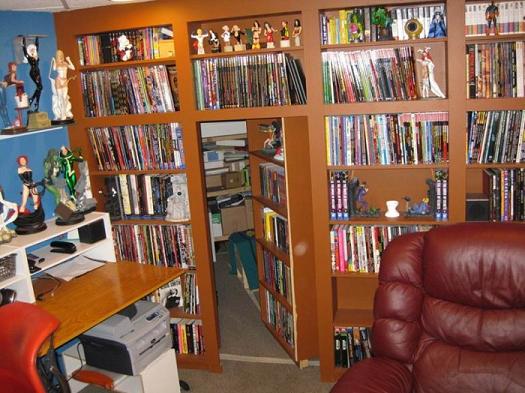

Essential Captain America Vol. 04

Steve Englehart, Sal Buscema, Frank Robbins and friends

Reprints: Captain Amercia #157-186 (January 1973 – June 1975)

Get this for: Englehart gives Cap a wakeup call — four stars

And so I come to the end of my little experiment of reading fifty Essentials in fifty days. It’s not always been a pleasure to read these collections and review them, but I thought to end the series on a high note. Essential Captain America Vol. 04 continues Steve Englehart’s run on the series and includes his most famous Captain America story as well. This is a run that has been often refered to since, especially the Secret Empire saga, both inside Captain America itself and in other Marvel titles, but not one I had read before.

Reading such highly regarded but possibly dated stories is always a bit of a crapshoot — will their reputation be validated or turn out to be overblown. For the stories collected here the verdict is mixed, as there are a couple of duds mixed in with the obvious classics. The worst being the four part Deadly Nightshade/Yellow Claw series in #164-167. The Yellow Claw — Marvel’s version of Fu Manchu before they got the real thing — is an embarassing yellow peril cliche here, while Nightshade is a blaxploitation cliche equally cringe worthy. That’s the low point of the collection, more than balanced out by the good stuff.

Now until Steve Englehart started writing him, Captain America was always a straight law ‘n order guy, on the side of the establishment, comfortable being a freelance agent for SHIELD. Previous writers, including Stan Lee had allowed some doubt to seep in, but it was only under Englehart that Cap being less and less comfortable with being a government man and it’s in this collection that things come to a boil. Considering when these issues were written, during the height of the Watergate scandals and the mistrust in government in America in general, it’s not surprising that some of this echoes in Captain America, but Englehart does much more than that.

In his most famous story, the Secret Empire saga, Englehart makes Cap the victim of an old adversary’s unusual revenge, as the ad writer turned supervillain the Viper uses his connections on Madison Avenue to start a campaign against Captain America, through the Committee to Regain America’s Principles. That turns out to only be the start of the conspiracy against him, as he’s framed for murdering another old villain, the Tumbler, then taken into arrest by Moonstone, the Committee’s new superhero and replacement for Cap. Things only get worse when he is forced to escape prison, then helped by his partner the Falcon goes looking for evidence to clear his name, as they run into the X-Men, who themselves are looking for why mutants are disappearing.

Their problems turn out to be related of course, as the Secret Empire turns out to be behind both, with the disappeared mutants being used to power their machinery. (All this happened when the X-Men no longer had their own title by the way, which is why they kept on wandering through titles like Captain America and The Avengers.) Cap and the Falcon manage to infiltrate the Empire’s headquarters just as they launch their assault on the White House, the plan being to “defeat” Moonstone as the defender of America and then use their agents in place all over the country to launch a coup. When Captain America and the Falcon foils these plans, the Secret Empire’s number one flees into the White House and commits suicide, after Cap pulls off his mask and looked in shock at the not seen by us person in “high political office”. So shocked he is, he gives up being Captain America the next issue, but the identity of the Secret Empire’s leader is never revealed.

It’s Nixon of course.

It’s never been officially confirmed, but who else could it have been to have this effect, Henry Kissinger? But Marvel could of course never say this outright; imagine the outrage by the seventies’ teaparty equivalents. A pivotal moment in Captain America’s development, something subsequent writers would come back to again and again. It’s not just Cap’s crisis of faith and rejection of his identity that e.g. Mark Gruenwald and Mark Waid would come back to, but also the resolution of it, Cap’s realisation that he’s not a symbol of the US government, but of the American Dream. Corny perhaps, but Englehart did hit on something real, something that was always true about Captain America. He never was a jingoistic symbol of my country right or wrong, but somebody who punched out Hitler on the cover of his first issue a year before America joined World War II. He’s everything that’s right about America, while never closing his eyes to what’s wrong with the country either.

In the aftermath, Englehart keeps Captain America out of uniform for no less than seven issues, with only the Falcon there to provide superhero action against old X-Men villain Lucifer for the first two issues, before Cap returns as the Nomad to take on the renewed Serpent Squad. This is another classic story I’d so far only encountered in synopsis, as the Serpent Squad kidnaps the president of Roxxon Oil, subject him to the ancient evil magic of the socalled Serpent Crown, then use him to get to an experimental oil platform which they want to use to raise Lemuria from the ocean floor. I’ve always been a sucker for Serpent Crown stories, ever since I first came across it in a Marvel Team-up story.

When Captain America finally returns as himself, it’s to take on his worst enemy, the Red Skull. It’s a decent enough story, but ends on an absolute downer, as it’s revealed that the Falcon, Sam Wilson, is in fact a career criminal from L.A. called Snap Wilson, brainwashed by the Red Skull when the Skull still possesed the Cosmic Cube to use as a hidden weapon against Captain America. It’s a wretched bit of writing that’s luckily been retconned since.

Let’s end this with a few words about the art. Most of it is provided by Sal Buscema, doing his usual dependable job, nothing spectacular but good enough. At the end though Frank Robbins replaces him and, well, it’s not good at all. The weird musculature he gives his characters and strange positions he draws them in, impossible for any real person, the overall “offbrand” effect of his art, it’s awful. Robbins was always more a newspaper strip cartoonist than somebody comfortable doing superhero comics and he certainly should not be judged by his work here, but boy is he a disappointment whenever he’s used on a Marvel title…

Conclusion? A great volume to end this series with. Tune in tomorrow for an epilogue/dissection of this whole mad project.