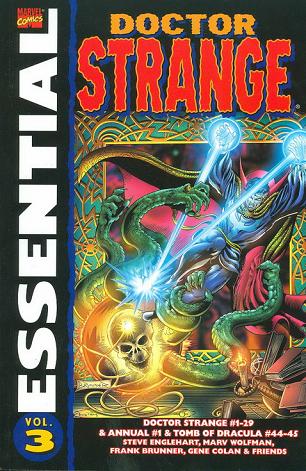

Essential Doctor Strange Vol. 03

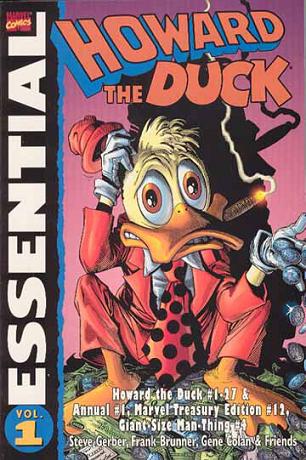

Steve Englehart, Marv Wolfman, Jim Starlin, Frank Brunner, Gene Colan and friends

Reprints: Dr Strange #1-29, Annual 1 and Tomb of Dracula #44-45 (June 1974- June 1978)

Get this for: Englehart and co trying to recapture the Ditko magic — three stars

I think it’s fair to say that every writer on Doctor Strange has tried to get out from under the shadow of Steve Ditko. In the first volume of

Essential Doctor Strange they did not succeed, but perhaps the writers in the third volume will fare better. They’re certainly not the least writers: Steve Englehart, Marv Wolfman, Jim Starlin and Roger Stern all have a go at Doctor Strange here.

Of the writers featured here, Englehart has the best chances. He was after all responsible for getting Dr Strange his own series again, together with Frank Brunner, through their work on Marvel Premiere. He starts strong, introducing Silver Dagger, a Catholic cardinal turned magician hunter, who in the first issue kills Doctor Strange and kidnaps Clea, his lover and disciple. Strange gets better of course, but it takes him five issues to put Silver Dagger away. In the sixth issue Gene Colan returns on the art duties, as do longtime Strange villains Umar and Dormammu in a plot to not only restore the latter one’s powers, but to make him master of Earth. In the end he’s only defeated by the powers of Gaea and every living creature on Earth — including the people reading the story…

The threats only get bigger for poor old Doctor Strange, having to face off against Eternity next for the fate of the Earth, failing to stop the destruction of the world in #12, only for it to be recreated the next issue. Everybody literally died that time, but was reborn a second time, something that would later in the volume be retconned by Marv Wolfman. It’s not the last time the universe is seemingly destroyed only to be recreated again — Wolfman does it as well, as does Jim Starlin in his Creators saga. This is no coincidence, as each writer has their own cosmic epic story to tell and what is more epic than the end of everything and only Doctor Strange remaining to put things right?

Yet lesser threats can work as well, as the crossover with Tomb of Dracula shows. When Strange’s servant Wong is bit and killed by Dracula, Doctor Strange goes looking for revenge only to fall victim to the vampire himself. He manages to escape in his astral body, but still has a hard time getting both himself and Wong cured and fails in destroying Dracula. After that it’s back to the big, existential menaces however, as Doc fights Satan, timetravels through America’s colonial history in honor of the bicentennial and confronts the menace of the Quadriverse and the Creators saga.

Reading this volume in one setting, rather than having read the individual issues spread out over four years, it’s not hard to see some patterns emerging — it’s not just the periodical destruction and recreation of the universe. There’s also the frequent depowering of Doctor Strange, as each writer finds reasons why he cannot use his magic this time. It is of course always difficult to write an almost omnipotent character like Doc Strange, who could end most threats with a handy spell or two. So either the villains need a power up or Strange needs a power down. Personally I feel either is a lazy choice and that’s the difference with the Lee/Ditko Doctor Strange; they didn’t take the easy way out. It takes effort and skill to keep Strange’s powers consistent and not cheat in getting him out of plot holes.

Another common plot device here is seeing Doc Strange being killed only to discover later that he managed to flee his body first in his astral form. I’ve got fewer problems with this, it is one of his established powers after all, but when used to much it can again be a crutch. The same goes for the eye of Agamotto, which is less used here however.

Frank Brunner starts out as the artist here and he’s is well suited to the title, as are his main succesors, Gene Colan, Jim Starlin, Ruby Nebres and Tom Sutton. Each of those artists is on the atmospheric end of the scale rather than the realistic, especially Colan. Lovely work by all of them and gorgeous to look at, even if some of it is hampered by the transition to black and white, as is the case with the P. Craig Russel drawn annual.

Some good tries, but the Ditko Doctor Strange is not equalled here.