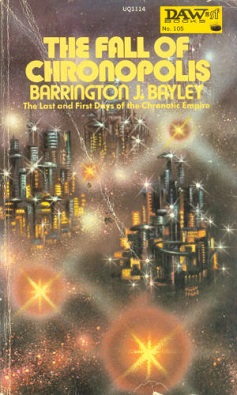

The Fall of Chronopolis

Barrington J. Bayley

175 pages

published in 1974

I’ve always been a sucker for time war novels, starting with Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity, Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time and Keith Laumer’s Imperium series. I like the grand scale on which these stories play out, the whole idea of the impermanence of time itself, something that undercuts our most basic of securities, the idea that the past we remember is the way that past has always been, making literal the idea Orwell put forth in 1984: he who controls the past, controls the future. Which explains why The Fall of Chronopolis was one of the first bought at Eastercon novels I finished, even before the convention itself was over, finishing it at the Dead Dog party on Monday.

In the The Fall of Chronopolis the time war rages between the Chronotic Empire, which has steadily increased its dominion over the centuries until it rule a thousand years of human history and its far future enemy, the Hegemony, existing futurewards beyond the Age of Desolation after the fall of the Chronotic Empire. For the most part this time war has been limited, consisting of limited raids on each other’s history, but the Chronotic Empire is raising a grand fleet of timeships to invade the Hegemony directly, while the latter had developed a time distorter which can warp history directly. But this is only the surface story; there’s a lot more going on