In his review of More Women of Wonder, James quotes Eleanor Arnason:

“As I said above, what I find interesting about the Bradford discussion is—40 years of history have disappeared. Both the people defending women SFF writers and the people saying women can’t write SFF sound as if they are back in the 1970s. I am disturbed by this, because my writing history is one of the things being disappeared. I have vanished as a writer in this discourse.”

Which struck me because I’d seen the same complaint from Kate Elliot on Twitter not long before about the erasure of her own work from SFF history:

We’re currently in a period where science fiction is slowly learning that women do write and read science fiction, where a new vanguard of high profile female writers is makig waves again. The problem is, we’ve been there before. We’ve been there in the nineties, with the stablishment of the Tiptree Award in the wake of the backlash against feminist science fiction in the eighties and before that, in the first wave of feminist science fiction in the seventies. That latter shoved under the carpet by cyberpunk, as Jeanne Gomoll pointed out in her open letter to Joanna Russ (originally in Aurora 25):

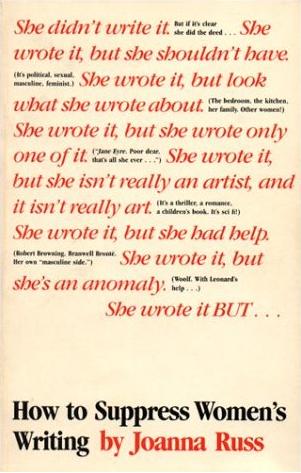

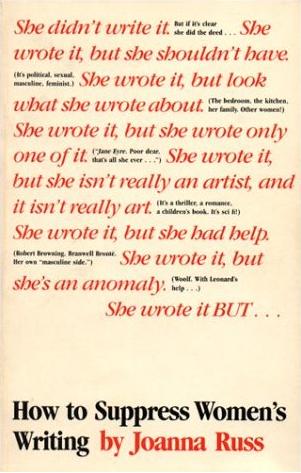

You observed some of the strategies that suppress women’s writing: “She wrote it, but she wrote only one of it,” or “She wrote it, but she had help,” or “She wrote it, but she’s an anomaly.” Well, the late 1970s and early 1980s spawned many women SF writers who wrote quite a bit of highly praised fiction. The old strategies don’t quite work. Here’s the new one: “They wrote it, but they were a fad.”

[…]

In the preface to Burning Chrome, Bruce Sterling rhapsodizes about the quality and promise of the new wave of SF writers, the so-called “cyberpunks” of the late 1980s, and then compares their work to that of the preceding decade:

“The sad truth of the matter is that SF has not been much fun of late. All forms of pop culture go through the doldrums: they catch cold when society sneezes. If SF in the late Seventies was confused, self-involved, and stale, it was scarcely a cause for wonder.”

With a touch of the keys on his word processor, Sterling dumps a decade of SF writing out of cultural memory: the whole decade was boring, symptomatic of a sick culture, not worth writing about. Now, at last, he says, we’re on to the right stuff again.

And this is happening still, if not done so obviously perhaps. I’m guilty of it myself, of ignoring writers like Kate Elliot for far too long, who haven’t been commercially successfull for decades, but who haven’t had much critical attention in all that time. Compare for example Tanya Huff with John Scalzi: both have had commercial success writing good old fashioned adventure science fiction and fantasy, but the Old Man’s War has gotten much more critical reception than Huff’s similar Confederation series. Is this just because Scalzi is a better self promoter, or because it’s easy for fan and critic alike to imagine him as the new Heinlein, while Huff, isn’t?

The history of science fiction is rewritten each year, every decade, but too often it’s still a parade of white men with only the occassional exceptional woman or writer of colour admitted. You can see that logic at work in the Gollancz Science Fiction Masterworks series. If you look at the current crop of Masterworks, not only is the gender imbalance wildly in favour of male writers, those female writers who are on the list are often feminist writers (Russ, Tepper, Tiptree, Le Guin (by default if not inclination)) or represented with atypical science fiction novels (Karen Joy Fowler’s Sarah Canary, M. J. Engh’s Arslan, Cecilia Holland’s Floating Worlds), but much fewer mainstream science fiction authors are represented (Brackett, Wilis, perhaps Griffith). If you look at the earlier series it’s even worse: it’s Sheri S. Tepper, Kate Wilhelm or Ursula Le Guin and together they’re represented by as many entries as Arthur C. Clarke has on his own.

Therefore the impression you get looking at the series is that women write less science fiction than men and when they do, it’s more likely to be political, feminist or in another way not “real” science fiction. It tells a story of the history of science fiction as written by men, where you go from Wells by way of Clarke and Aldiss through Silverberg, Dick and Moorcock to Reynolds and Ryman. It’s where the first draft of sf history is written, in series like this, anthologies with no or few female contributors and with review venues which pay much more attention to male than female writers, publishers with barely a female writer in their roster. We’re sort of getting a little bit of a pushback going in the last six, seven years, more attention for writers who aren’t white, straight cis men, but as Gomoll’s open letter from the mid eighties shows, it’s still easy to dismiss all this once the initial energy of the writers and critics involves dissappates, as it must. Yes, there are grass roots initiatives like Ian Sales’ SF Mistressworks or Nicola Griffith’s The Russ pledge, but those can only do so much.

If we want science fiction to be diverse, we need to be committed to it on every level in science fiction, as reader, critic, editor, writer and publisher, to make the history as well as the present of science fiction be about more than just the usual suspects, to not forget those female writers who also shaped our culture, but weren’t recognised for it. Andre Norton needs to be remembered in the same way as Robert Heinlein, Melissa Scott needs the same recognition as Lewis Shiner, to recognise that the list James put together off the top of his head:

Lynn Abbey, Eleanor Arnason, Octavia Butler, Moyra Caldecott, Jaygee Carr, Joy Chant, Suzy McKee Charnas, C. J. Cherryh, Jo Clayton, Candas Jane Dorsey, Diane Duane, Phyllis Eisenstein, Cynthia Felice, Sheila Finch, Sally Gearhart, Mary Gentle, Dian Girard, Eileen Gunn, Monica Hughes, Diana Wynne Jones, Gwyneth Jones, Leigh Kennedy, Lee Killough, Nancy Kress, Katherine Kurtz, Tanith Lee, Megan Lindholm, Elizabeth A. Lynn, Phillipa Maddern, Ardath Mayhar, Vonda McIntyre, Patricia A. McKillip, Janet Morris, Pat Murphy, Rachel Pollack, Marta Randall, Anne Rice, Jessica Amanda Salmonson, Pamela Sargent, Sydney J. Van Scyoc, Susan Shwartz, Nancy Springer, Lisa Tuttle, Joan Vinge, Élisabeth Vonarburg, Cherry Wilder, Connie Willis, Marcia J. Bennett, Mary Brown, Lois McMaster Bujold, Emma Bull, Pat Cadigan, Isobelle Carmody, Brenda W. Clough, Kara Dalkey, Pamela Dean, Susan Dexter, Carole Nelson Douglas, Debra Doyle, Claudia J. Edwards, Doris Egan, Ru Emerson, C.S. Friedman, Anne Gay, Sheila Gilluly, Carolyn Ives Gilman, Lisa Goldstein, Nicola Griffith, Karen Haber, Barbara Hambly, Dorothy Heydt (AKA Katherine Blake), P.C. Hodgell, Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Tanya Huff, Kij Johnson, Janet Kagan, Patricia Kennealy-Morrison, Katharine Kerr, Peg Kerr, Katharine Eliska Kimbriel, Rosemary Kirstein, Ellen Kushner, Mercedes Lackey, Sharon Lee, Megan Lindholm, R.A. MacAvoy, Laurie J. Marks, Maureen McHugh, Dee Morrison Meaney, Naomi Mitchison, Elizabeth Moon, Paula Helm Murray, Rebecca Ore, Tamora Pierce, Alis Rasmussen (AKA Kate Elliott), Melanie Rawn, Mickey Zucker Reichert, Jennifer Roberson, Michaela Roessner, Kristine Kathryn Rusch, Melissa Scott, Eluki Bes Shahar (AKA Rosemary Edghill), Nisi Shawl, Delia Sherman, Josepha Sherman, Sherwood Smith, Melinda Snodgrass, Midori Snyder, Sara Stamey, Caroline Stevermer, Martha Soukup, Judith Tarr, Sheri S. Tepper, Prof. Mary Turzillo, Paula Volsky, Deborah Wheeler (Deborah J. Ross), Freda Warrington, K.D. Wentworth, Janny Wurts, and Patricia Wrede

…is only the tip of the iceberg.