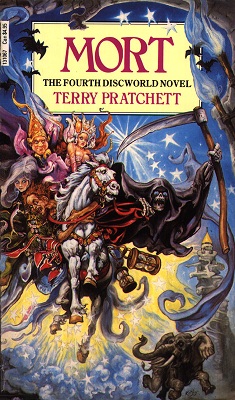

Mort

Terry Pratchett

272 pages

published in 1987

If anybody can lay claim to being the first breakout star of the Discworld series, it has to be Death. Started off as a bog standard personification of an abstract concept, managed to work his way up through several cameos in the first three books to this, his first start turn in a novel. Four more would follow, though none in the past decade. He’s not quite his cuddly self here yet, still a bit on the evil side, not as human as in e.g. Hogfather.

Nevertheless Death is being humanised, or why else would he end up looking for an apprentice? Anthropomorphical personages don’t need successors, now do they? Yet still Death ends up on a dusty market square in a small village at the stroke of midnignt taking on a most unlikely apprentice: Mort. Mort is one of those boys who are all knees and legs, who think too much for what they’re doing. An apprentice with Death is literally his last opportunity, but as his father said, there may be opportunities for a good apprentice to eventually take over his master’s business, though Mort is not sure he wants to.