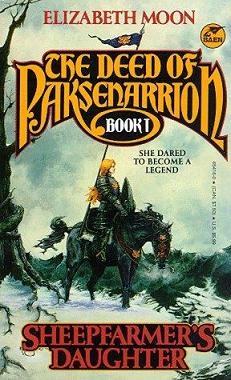

Sheepfarmer’s Daughter

Elizabeth Moon

506 pages

published in 1988

Sheepfarmer’s Daughter was Elizabeth Moon’s first published novel and is now available from the Baen Free Library as a sample to get you to try her other work. I got it to have something to read in those stolen moments where it’s too much hassle to dig a paperback out of my bag, but I can get to my mobile. Sheepfarmer’s Daughter was the ideal book for this: not overtly complicated, easy to read in small chunks without missing much of the plot and engaging enough to keep reading.

I’ve only read one Elizabeth Moon novel before this one, A Sporting Chance, a science fiction adventure story that was decent enough but nothing special. From all I had read about her other novels, they seemed much the same so until now I’d never really sought out her books. But it’s hard to argue with free books and people I trust had been praising Sheepfarmer’s Daughter, so when I needed something new to read the choice was easy.

Sheepfarmer’s Daughter is the first in a trilogy called The Deed of Paksenarrion, which Elizabeth Moon allegedly wrote after she was introduced to Dungeons and Dragons by friends of her and got annoyed by the way it handled paladins, to show what real paladins were like. A paladin is “a holy knight and paragon of virtue and goodness”, as Wikipedia calls it and in D&D it’s one of the character classes you can play. What exactly Moon disagreed with I’m unclear about, but there certainly is some D&D influence visible in the fantasy world she created. The other influence on the series was Moon’s own background as an US Marine, giving her a somewhat more realistic idea of warfare than many other fantasy writers have.