in a discussion about what would happen once “Moore’s Law” no longer holds true over at James Nicoll’s place, Charlie Stross said the following:

And then there’ll be a huge recession and layoffs, just as there was in aerospace around 1970 when the industry hit a performance wall (note that airliners today fly no faster than they did in 1970 — Concorde’s champagne quaffing elite aside, travel at over Mach 0.9 is not commercially sustainable).

To which Alex Harrowell took exception

Forget Princess Margaret. Civil aviation only became interesting economically or sociologically after Charlie’s performance wall – we’ve had David Frost commuting for the BBC from London to New York, we’ve had Easyjet ravers/poverty jetset types bouncing from sofa to sofa around Europe, Viktor Bout’s inverted triangle trade shipping diamonds out of Africa and guns in, enabled by cheap Antonov-12s and international free trade zones, Kenyan farmers discovering they could get backload freight to Europe for pence. Before the “performance wall”, people watched movies about air hostesses; after, they actually flew.

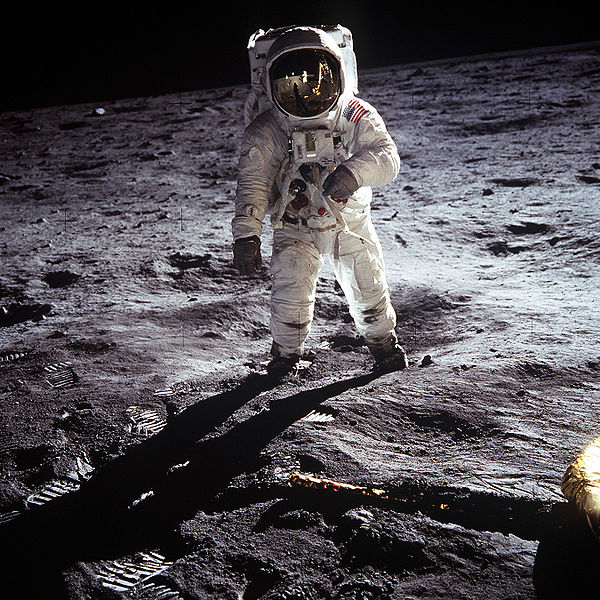

Shades of endless rec.arts.sf.written discussions about the slowing down of progress, as measured by the speed of air travel. “We went from the Wright brothers to supersonic flight in less then fifty years and since then we’ve only gone backwards”. It’s even worse with space travel of course, with the complaints of how we went to the moon in ’69 and now can’t even get the shuttle in orbit; the fortieth anniversary celebrations aren’t helping either. The horrible truth about science fiction is that a lot of it is obsessed with Top Gear notions of progress: more power, more speed, bored with everything else.

Science fiction got its start in the twenties, a decade that was absolutely bursting with this kind of easy to understand technological progress: the maturing of radio into a mass medium, the development of the airplane into something that could cross the Atlantic, the first stirrings of television and rocketry, giant new insights in the nature of our universe, the atom, etc. Science fiction surfed this wave of techno-optimism until roughly the early sixties, but since then it has had to confront the reality that all its dreams were actually quit a bit harder to realise than it had made it seem. Easy travel to other planets, human-like robots, unmetered atomic power, artificial intelligence, flying bloody cars: all dreams that didn’t come true, or came true in ways that didn’t fit the Glorious Science Fiction Future. It’s no wonder the New Wave, the first movement in science fiction to not just question its assumptions, but even wonder out loud how important or even interesting these assumptions were in the first place, happened at the same time.

While the best science fiction has long since digested the reality that technological progress is hard, non-linear and more interesting in what it makes possible than in what it can do, there are still plenty of fans who think that just because their daily lives look superficially similar to how they lived ten or twenty years ago, there hasn’t been any progress. For those fans the idea that Moore’s law will end means their last big hope at getting to the technoutopia of their dreams, the Singularity, has ended. Charlie isn’t one of them, however; I think he was just a bit sloppy in the example he chose.