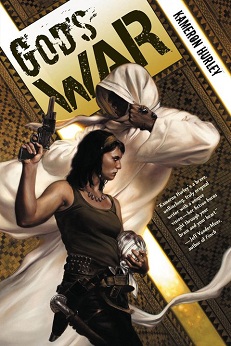

God’s War

Kameron Hurley

286 pages

published in 2011

The main problem with God’s War is its setting. Kameron Hurley’s debut novel is set in an unspecified far future, on the alien planet of Umayma, featuring an unending, religious war between Nasheen and Chenja, Umayma’s biggest nations. The war has warped both nations’ societies, with each country’s men either dead or at the front, leaving only the very young and very old at home. Despite both societies’ innate conservatism that has left women to take up the slack, having to take on traditional male roles, resulting in what’s best called a violent matriarchy in Nasheen, with women in all positions of power and the men constantly being sacrificed at the front. Nyx, its protagonist, is a brutalised, aggressive, scary woman, a deliberate attempt by Hurley to create the female equivalent of somebody like Conan while the background against which Nyx plays out her story was meant to show how a brutal, violent hierarchical society doesn’t magically become better because women are now in power, how easy it is for women to keep perpetuating the same violence and abuse as the men, just with different people in the victim and oppressor roles.

It’s an interesting concept, but the execution is troubling. Because while it is set on another planet far in the future and the politics and religion that’s being fought about is fictional, the images that Hurley creates are very familiar, because the religion she creates looks a lot like Islam, veiled women, multiple daily prayers, holy book and all, with the war and the societies it has left in its wake familiar from what we’ve seen on the news from Iraq or Lybia or even Chechnya. The landscapes are all desert landscapes, the cities are Middle Eastern, with mosques and minarets, often broken, often bombed out. As Tariqk put it, it’s as if Hurley “took every stereotypical Arab world depiction & TURNED IT TO 11”. It’s this orientalism that fails this novel, this inability to do more than use orientalist stereotypes, that reduces it to just another grim and gritty adventure story when it could’ve been so much more.