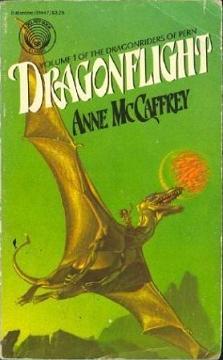

Dragonflight

Anne McCaffrey

303 pages

published in 1968

Because I’ve been running my booklog since 2001 I know it’s at least a decade or more since I’d last cracked open an Anne McCaffrey novel, yet once upon a time her The Dragonriders of Pern series was very important to me. Like so much science fiction and fantasy I discovered the Pern books through the local library, first reading them in Dutch, then continuing in English after I discovered the later books were only available that way. Over the years I devoured everything of McCaffrey I could lay my hands on, but I got less and less enjoyment out of her later novels, until I stopped reading them all together. Which is why I hadn’t read her in more than a decade and why it took her death to get me to reread the Pern novels. Which is a shame, as rereading them now makes clear how good McCaffrey at her best really was.

And Dragonflight was the best story she ever wrote. The two novellas that form the first twothirds of it, “Weyr Search” and “Dragonflight were rewarded with a Hugo and a Nebula Award respectively and are worth it. I had remembered Dragonflight as a fairly light novel, but it actually starts out quite dark, with Lessa, its heroine being the sole survivor of a coup against her family, plotting revenge as a kitchen drudge against the evil lord Fax who had taken over her hold. She’s not a nice person at all at the start of the story, completely focused on getting her own back and on making the hold as miserable as possible. But she also has a secret, a bond with the watch wher, a telepathic reptile like animal used as a watchdog. Little does she know that this is a hint to a much greater destiny for her…