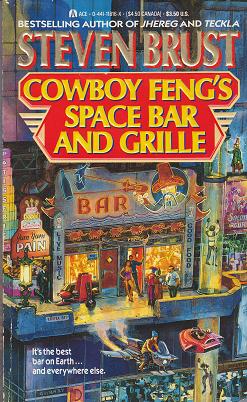

Cowboy Feng’s Space Bar and Grille

Steven Brust

223 pages

published in 1990

Sometimes when I’m depressed I go on a book reading binge — I managed to read every Wheel of Time book up to Lord of Chaos in a week when I was at a low point during my time at college. Pure escapism, fleeing into a story to temporarily ignore the world around me. A few weeks ago I fled back in that habit when my wife was having a very bad night, the day before she had to go back to hospital again. I was sleeping on the couch to try and give her an easier night’s sleep but then couldn’t sleep myself, so I grabbed the nearest book at hand. This turned out to be Cowboy Feng’s Space Bar and Grille.

Which perhaps wasn’t the best book to keep the night terrors at bay. Cowboy Feng’s Space Bar and Grille is a strange book, if only because it’s one of Steven Brust’s rare science fiction novels, but also because it’s a light adventure story about a Strange Bar, set amongst a series of nuclear holocausts. Amongst Brust fans it’s apparently a bit of a controversial book with some hating it, but for me it was the right book at the right time. It may be strange to think of a book that has a succession of nuclear wars at its heart as comforting, but that’s what it was.

It’s comforting because Brust makes it so. The nuclear death is in the background, while in the foreground we get the story of the bar that has the best matzo ball soup in the galaxy, as well as some of the best Irish musicians. Whether or not Billy, the protagonist narrating the story in first person, counts himself amongst them remains unrevealed. This is the picture you get in the first few sentences and the cozy atmosphere it evokes neutralises much of the existential dread the nukes evoke. It reminds me of the urban fantasy people like Emma Bull and other of the Scribblies — a group Brust of course belonged to too — were writing in the eighties.