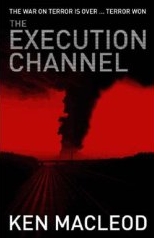

The Execution Channel

Ken MacLeod

307 pages

published in 2007

The Execution Channel is MacLeod’s newest science fiction novel and a return to the sort of book he made his name with, after several more traditional sf novels: intensily political, near future novels in settings that seems to flow logically from our own times and as a reaction to contemporary political developments. In science fiction the urge to respond to current events often results in shallow, cliched tripe, but that’s never the case with Macleod, largely because he’s a better writer than that, but also because he doesn’t as much respond to a single event as to the general direction politics is taken. In his Fall Revolution novels he was partially responding to the accelerating pace of globalisation and the role of the US as a caretaker superpower, here it’s the War on Terror and the emergence of the hypersecurity state and the increasing brutalisation of our societies as a result of this, made visible by the concept of the execution channel. Which is exactly what it sounds like, a tv channel dedicated to showing state sanctioned killings.

MacLeod has been at his best so far when he’s writing near-future science fiction and The Execution Channel is about as near-future as you can get, set perhaps ten years from now, perhaps only five. It’s a future in which all the fears we’ve had and still have about the War on Terror have become true: American and British troops not just in Iraq and Afghanistan anymore, but all over the Middle East, while in Britain itself the security state has taken over, terrorism is rampant and this in turn has led to pogroms against Muslims. And then a military airfield, RAF Leuchars, is hit by what looks like a nuclear attack. From there on things get worse.