Failed ex-engineer with lack of self awareness thinks all men are potential rapists, not just him.

Found via, like so much other brain bleach material, via James.

Failed ex-engineer with lack of self awareness thinks all men are potential rapists, not just him.

Found via, like so much other brain bleach material, via James.

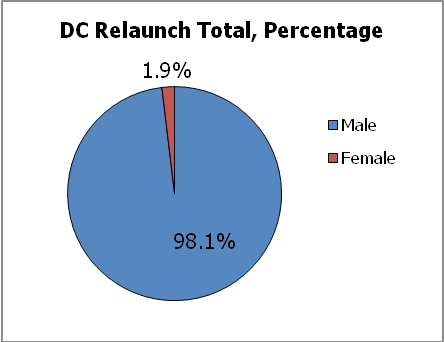

As you might have noticed DC comics is rebooting its entire superhero line and Tim Hanley at Bleeding Cool took some time to look at how it all worked out, gender balance wise. Turned out of the one hundred and sixty named creators, only three were female…

Not that it was much different before the reboot; Gail Simone is the only truly high profile female creator working on a DC superhero title right now if I remember correctly. See, science fiction is not the only field that has problems with its gender balance… It’s always been bad in superhero comics, but as bad as this?

If you know anything about feminism, you probably know about how feminist history can be roughly divided into three different waves of activity. In that scheme the first wave of feminism took place in the late 19th and early 20th century and focused on winning women equality before the law (right to vote, stand for election, get an education and so on), the second wave of feminism hit in the sixties and seventies, focusing on winning economical and societal equality (equal work for equal pay, getting out of restrictive gender roles, women winning control over their own reproductive systems and all that jazz) and the third wave started sometime in the nineties or perhaps earlier, focusing more on cultural issues and the interaction between sexism and racism, gender and sexuality and so on. Each wave built on the accomplishments of the preceding ones, while carrying the struggle into areas left untouched by them. It’s a massively simplified view of feminist history of course, based mainly on American experiences not always applicable to other countries and it leaves out everything that happened before the first wave or inbetween waves, but that’s only the start of the problem.

The real problem is that much of the difference between the various waves is political. Now nobody but historians really cares about first wave feminism anymore and all the people involved with it are long dead, but things are different for second and third wave feminists, both generations still very much alive and not always understanding each other. As with most movements, the differences between the two can often be decidedly minor to outsides, more a question of difference in degree rather than kind, but for those in the middle of the struggle they can look enormous. Especially on the internet, where everybody has a voice and is an expert — second versus third wave feminism leads to almost as many flamewars as gun control does. These sort of debates can be hugely counterproductive, especially when taking place in the context of bigger battles.

Case in point, when Cheryl Morgan gives the following definition of second wave feminism in an otherwise sensible post teasing out the impact of different notions of feminism on modern UK science fiction and why it’s so seemingly unfriendly to women, it doesn’t help:

Second wave feminism was the movement that started in the 60s and 70s. In theory it was about equal rights for women in all areas of life. In practice it was sometimes more about equal rights for middle class white women, and occasionally about the rights of middle class white lesbian separatists.

That’s cherrypicking and caricaturing the very worst aspects of second wave feminism, as seen through the lens of several decades worth of backlash. If your view of a second wave feminist is a bra-burning lesbian until graduation willing to pull the ladder up behind her as soon as she and her friends have broken the glass ceiling, that’s the backlash talking. Yes, there have been class and race issues with classical feminism that modern feminism is attempting to avoid and correct, but we should not forget that much of what third wave feminism concerns itself about was an issue for second wave feminists as well. That it sometimes degenerated into “equal rights for middle class white women” is not a feature of second wave feminism as such, but more of its defeat; the co-opting of parts of it by the patriarchy or the capitalist system or whatever you want to call it.

In the context of what so far has been a relatively fruitful debate about how to fix science fiction, especially British science fiction to make it less excluding towards women, such a sneer is unnecessary and unhelpful.

One Magemanda isn’t keen on the current attention given to the continuing gender imbalance in science fiction, claming so totally NOT on board with this focus on women in literature:

1) In any other workplace, if people were determined to focus on the specifics between men and women, there would be a good case for a charge of sexism.

2) Women have been fighting for equality for years: why is this suddenly a new story?

3) In chick lit, there is not a fierce desire for there to be a slew of male authors – no one argues that Mike Gayle should be as widely read as Marian Keyes. Authors are enjoyed on their own merits.

4) Last night I was watching the Great British Menu and the commentator described one of the judges as a top female chef – and I felt insulted that she wasn’t just considered to be a top chef. The same can be applied to authors: we should be insulted at having to focus on women separately.

For me, this is the height of a storm in a teacup, and I’m so tired of hearing about it now.

Why not consider it this way:

Read the books you like. Enjoy the books you read. Who cares the sex of the authors writing them? I certainly don’t! Do you?

A naive and ill thought out response perhaps, but one that needs to be answered. I suspect there are quite a few science fiction readers who likewise don’t get what the fuss is about and wonder why they should care about “the sex of the authors”. You cannot force people to care about the political implications of their entertainment choices; you’ll have to convince them. Magemanda’s post offers a good opportunity to do so.

The reason why feminism and the continuing gender imbalance in science fiction has gotten back on the agenda is simple: the death of Joanna Russ. An outspoken feminist icon and writer, her death and the renewed focus on her work that it inevitably brought made painfully clear how little has changed since she first criticised science fiction for ignoring its female writers. And while there had been a renewed interest in making science fiction more inclusive these past few years, Russ’ death was the catalyst that spurred people to action.

So, no this is not a new story, but that doesn’t matter. It’s still important. Science fiction suffers if we ignore half the people writing it. But last year several of us discovered this was exactly what we had been doing by “enjoying the books we read and not caring about the sex of the people writing them” and –surprise surprise– discovering the overwhelming majority of writers were male. By reading on autopilot, I missed quite a bit of good science fiction written by people not on my radar. I needed to consciously think about the kind of authors I wanted to read to redeem my mistakes. That’s why even as a reader it pays to look at what you’re reading, to make sure you’re not missing books you’d enjoy just because their author isn’t part of your usual circle.

Reading between the lines, I got the impression Magemanda thinks projects like Ian Sales’ SF Mistress Works is about separating out the women from science fiction, putting them in a separate league like with womans’ sport. But this is not the intention at all. We I think we’ve proven by now is that if we don’t make a fuzz about female writers, especially as male readers and reviewers, we run the risk of forgetting about them, of neglecting them. That’s why we need to pay more attention to female writers, even if in an ideal world the gender of a writer shouldn’t matter.

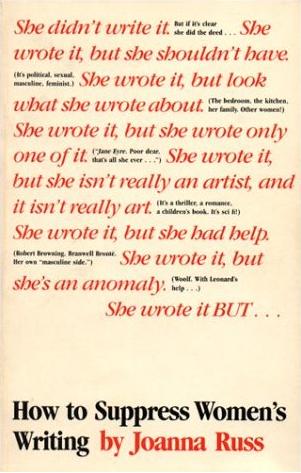

“She didn’t write it. But if it’s clear she did the deed… She wrote it, bit she shouldn’t have. (It’s political, sexual, masculine, feminist.) She wrote it, but look what she wrote about. (The bedroom, the kitchen, her family. Other women!) She wrote it, but she wrote only one of it. (“Jane Eyre. Poor dear. That’s all she ever…”) She wrote it, but she isn’t really an artist, and it isn’t really art. (It’s a thriller, a romance, a children’s book. It’s sci fi!) She wrote it, but she had help. (Robert Browning. Branwell Brontë. Her own “masculine side”.) Sje wrote it, but she’s an anomaly. (Woolf. With Leonard’s help…) She wrote it BUT…”

That’s the cover of How to Suppress Women’s Writing, Joanna Russ’ classic examination of all the ways women’s writing has been written out of literary history. The cover sort of gives the game away in how that was and is done. It’s so easy to outright deny or minimise female contributions to literature, consciously or unconsciously because despite a century of feminism, we’re still living in a male orientated world. Whether we like it or not, people like me — white, western, male, straight — are the default and if we don’t watch ourselves we find it easy to ignore all those not like us, while immediately finding it strange if we’re not present in our fictions, either as author or character.

In science fiction, despite its self asserted reputation of openmindedness, things are no better. If have been following this blog for a while, you know this, as we hashed this all out last year as well. That’s why I started a project to read at least one science fiction or fantasy book written by a woman per month, just to counter my own subconscious tendency to stick to male authors. The personal is the political after all and if I don’t take the trouble to look after my own reading, I can’t really fault others for ignoring female writers. It may seem odd to police your pleasure reading that way, but I’ve found that if I don’t, I get stuck in the same rut with the same male authors over and over again. I don’t just do it because it’s good for science fiction if more people pay as much attention to female as to male writers, but because it’s good for me.

Just because a few of us felt this way last year, doesn’t mean the war is being won of course. At the moment science fiction has gotten a bit more media attention again, if only through the by all accounts brilliant exhibition at the British Library, but sadly it has revealed that it’s still the male writers who get most of the attention. As Nicola Griffith found out, when The Guardian asked its readers to name its favourite sf books/writers, only 18 out of 500 writers were female. It reminded her of what Joanna Russ had analysed so well thirty years ago and it inspired her to a call for action:

Clearly, women’s sf is being suppressed in the UK. Oh, not intentionally. But that’s how bias works: it’s unconscious. And of course sometimes it’s beyond a reader’s power to change: you can’t buy a book that’s not on the shelf. You can’t shelve something the publisher hasn’t printed. You can’t publish something an agent doesn’t send you. You can’t represent something a writer doesn’t submit. Etc.

But, whether this bias is active or passive, it’s time to attack it on several fronts:

- reexamine and rewrite Best Of lists to take into account women who have been relegated to also-rans (this will involve public discussion and reevaluation)

- rexamine and republish Classics to include those women who, through the process Russ delineates, have slipped down the rankings (ditto)

- revive the old-style Women’s Press list of sf, historic and contemporary, by women writers

- acknowledge, in media pieces, likely inherent bias

- writers, stop self-censoring

- agents, stop narrowing the funnel

- editors, consider balancing your list

- booksellers, pay attention to your readers and categories

- readers, give books and writers a chance

- etc.

And always, always name the behaviour around you: we can’t change behaviour until it’s named.

From there on, Nicola called for The Russ pledge:

The single most important thing we (readers, writers, journalists, critics, publishers, editors, etc.) can do is talk about women writers whenever we talk about men. And if we honestly can’t think of women ‘good enough’ to match those men, then we should wonder aloud (or in print) why that is so. If it’s appropriate (it might not be, always) we should point to the historical bias that consistently reduces the stature of women’s literature; we should point to Joanna Russ’s How to Suppress Women’s Writing, which is still the best book I’ve ever read on the subject. We should take the pledge to make a considerable and consistent effort to mention women’s work which, consciously or unconsciously, has been suppressed. Call it the Russ Pledge. I like to think she would have approved.

This in turn inspired Ian Sales, who had been part of the debate last year as well, to start the SF Mistress Works blog, dedicated fto establishing a line of potential “Mistress Works”, classical sf novels written by women, ala the actually existing Gollancz SF Masteworks line. He’s calling for reviews of those works he has already put up as potential Mistress Works, either existing or new ones; I might just take him up on that.

As long as it’s not as natural or easy to think of female sf writers as it is to think of male ones, the Russ Pledge and initiatives like Ian Sales’ are necessary. As Maura McHugh says in in the title of her excellent summing up of the current “controversy”, be part of the solution. Take the Russ Pledge today!