I’ve worked with Kobayashi-san. Not literally of course, but with women like her, testers and developers in an overwhelmingly male workplace, often the only woman in a department or team, sometimes pioneers. In the almost twenty years I’ve been working in IT I’ve seen a fair few of them and while the numbers of women in IT has crept up, my current team of fourteen still only has two female developers. Sometimes it seems IT has actually regressed in this regards, software development becoming more male dominated rather than less.

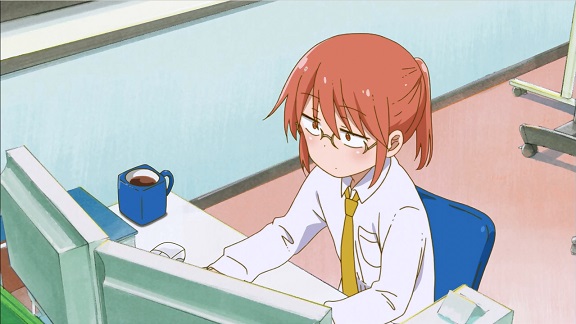

As we’ve seen throughout the series so far is that Kobayashi-san doesn’t dress very girly, shall we say. At home she wears comfortable, somewhat slobby clothes, jeans and sweaters. At work she dresses like her male colleagues, shirt and tie, not overly formal, but good enough for IT work. She gives the impression of not overtly caring about how she looks, other than being neat enough for the office. It stands in sharp contrast to the usual office lady we see in anime, dressed in a work uniform or at the very least in skirt and blouse; Kobayashi-san must be deliberately dressing as one of the boys, to not stand out or perhaps to not be mistaken for a secretary. You wonder what her co-workers make of her behind her back.

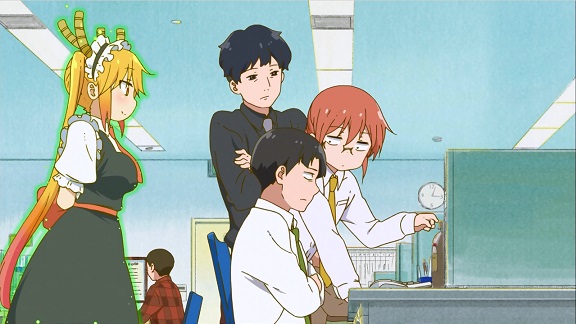

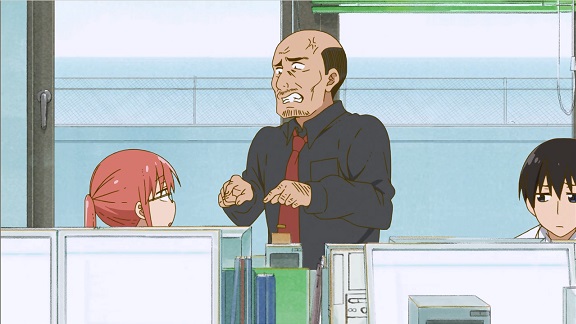

In episode five Tohru goes to visit Kobayashi-san in her workplace, giving us the first extended look at her work life. What struck me immediately was that she seemed slightly older and more experienced than her co-workers. She’s acknowledged as such too by the people she works with. Takiya ask her for help with his own projects and a little bit later we see her advicing two other co-workers, not to mention that she has to take over the project of a co-worker off sick in order to solve a problem that cropped up in production. Her expertise is at least unquestioned, but at the same time her nominal boss sees her as an easy target, expecting her to do his work, demeaning and belittling her and blind to the more important work she’s already doing. Not that Kobayashi is defenceless: we later find out that somebody dobbed her boss in with his superiors about his work ethics, getting him fired…

The mangaka behind the original manga apparantly drew inspiration from his own work experience in IT, which tells me some experiences are universal, because everything I mentioned above I’ve seen with female co-workers of mine. AsI said, I’ve worked with a fair few of slightly older, much more experienced and knowledgable, tough as nails women like Kobayashi-san. Not always appreciated them, but still.