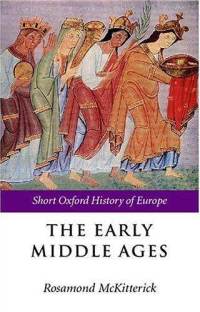

The Early Middle Ages

Rosamond McKitterick

308 pages including index

published in 2001

I spotted this book at the local library and got it out because it contained a contribution by Chris Wickham, whose Framing the Early Middle Ages and The Inheritance of Rome impressed me quite a lot when I read them earlier this year. The Early Middle Ages is one of the entries in The Short Oxford History of Europe and intended as an introduction to this particular period, what the editor Rosamond McKitterick called “the Boeing 767 view of early medieval Europe”, quite a different sort of book from the two Wickham books. I therefore didn’t expect to learn much news from this, but rather wanted to read it as an introduction to the other historians involved, none of whom I’d read before.

The Early Middle Ages attempts to give a broad overview of the evolution of Medieval Europe between 400 CE and 1000 CE and tries to evaluate this period on its own terms, rather than as a transition period between the Roman Empire and the “real” Middle Ages. Doing this in less than 250 pages, or some 80,000 words is a real challenge and of course means that a lot of history is elided. Ironically, if you are already familiar with the period, it helps a lot to understand some of the developments that are sketched out here, at least to put them into a chronological context. I’m not sure how much I would’ve understood of some the chapters had I come to this book as a complete novice. This feeling was the strongest in Chris Wickham’s chapter, which felt as an extract of his two books mentioned above…