Speaking of translating, as we were doing last Saturday, here’s an ancient fan rant about the sort of people who watch Very Japanese Anime:

It’s a show about Japanese references and Japanese wordplay. It’s not primarily a life sitcom or a slapstick act or anything “universal” like that. You could and should be watching something else – it’s not like we’re wanting for English sitcoms or sketch programs. If you’re watching it with English subs, or probably with any subs, you’re

- Japanese, but interested in how one would translate if one had the time on his hands.

- a pun-lover like me, but have made the inexplicable decision to look for your puns wedged forcefully into localizations of Japanese things instead of in one of the many well-crafted and legitimate sources of English puns.

- full of shit, watching this because you like anime just for being anime, and because you want to go read a bunch of explanations later and then congratulate yourself/brag about what a smart Japanophile you are and how you definitely totally got all the jokes.

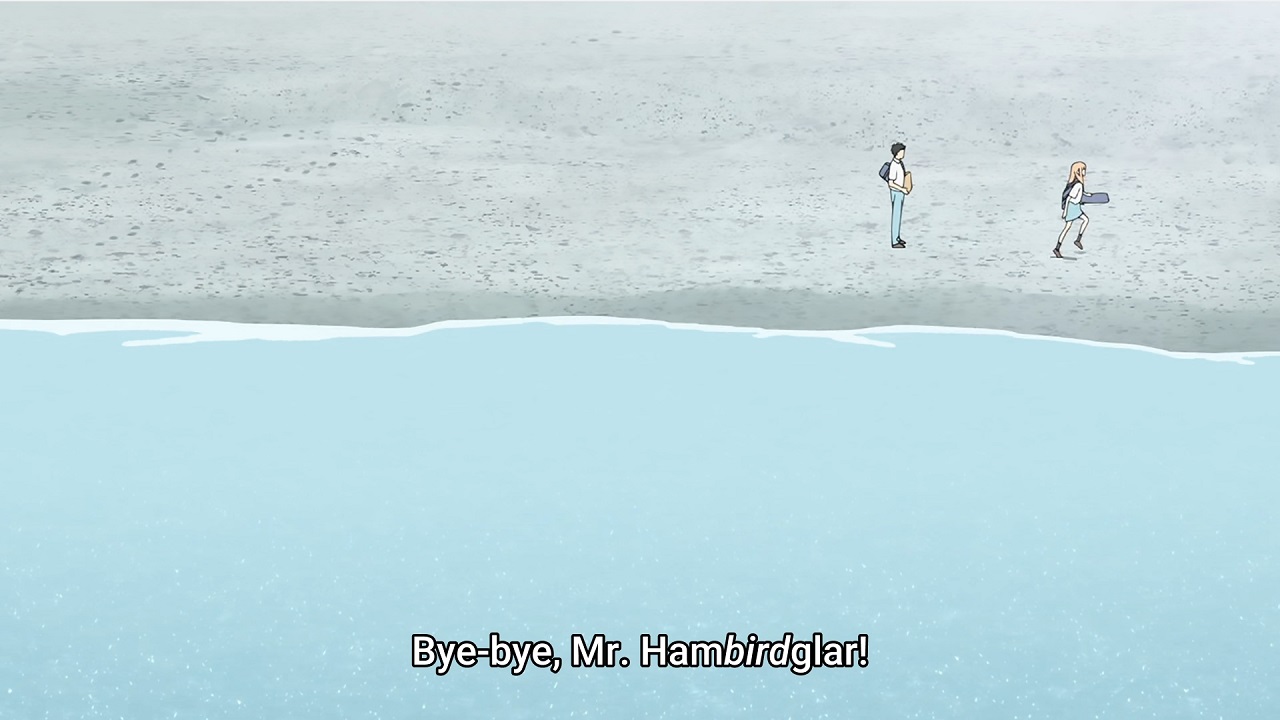

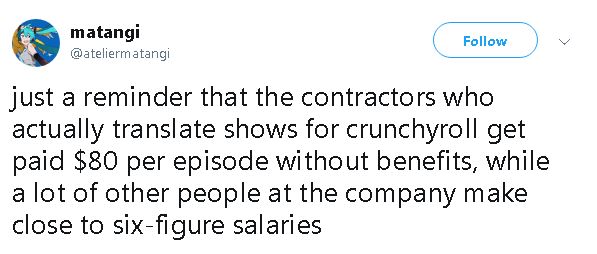

The show they’re talking about is Joshiraku, a 2012 slice of moe comedy series about a group of female rakugo performers. Rakugo is a Japanese storytelling art form with its roots in the Edo period and specialises in telling long, complicated mostly humorous stories, usually set in that period. The performer relies only on their storytelling technique, voicing each character themselves, using a small fan and cloth as props but apart from that relying only on their voice, mime and facial acting. The stories themselves are usually full of wordplay, puns and historical references so often hard to understand for non-Japanese. None of which matters for this series however, as the focus is instead on the four girls interacting with each other while they’re waiting to go on stage, or during the intervals or after having concluded a show. (The closest it comes to actual rakugo is at the start of the ending song. The problem is that their conversations, despite the anime’s emphasis that these are just “ordinary so that viewers can fully enjoy how cute the girls are”, they’re actually stuffed even more full of wordplay, puns and obscure references than the rakugo would’ve been. An impression of the difficulties this makes for translating and subtitling this mess can be found in the translator notes its fansubber left behind.

Nevertheless I did laugh. Even if ninetyfive percent of the jokes and references went over my head, I still laughed. To insist that you have to be either Japanese or fluent in the language enough to recognise the puns seems a bit harsh, as the original poster does acknowledge in their addendum. (A very Yankee mentality on display there, that confusion on why you’d want to watch something foreign instead of something more easily digestible and in English). To be honest, I didn’t go into Joshiraku with more on my mind than that it looked like a cute, funny series with a bit of a reputation of being ‘difficult’. That latter turned out to be exaggerated. Most of it was perfectly understandable even if many individual jokes or sight gags didn’t land for me. (Also a testament to its fansubber’s hard work!)

There’s another sort of pleasure to be had in this sort of dense, hyper layered material, the pleasure of getting to grips with it, seeing the patterns, understanding a certain reference or gag maybe only years or even decades later. Glimpsing a larger world through these half understood allusions. It’s very much the same thing as when I first started to read Marvel comics, similar to finding where an obscure sample in a rap song originally came from. It’s the sort of thing I’m always unconsciously looking out for in my entertainment. A nerdy sort of pleasure seeking, but a sincere one.