I was today years old when I learned the dancer in the music video for Kate Bush’s Running up that Hill, Misha Hervieu, is a trans woman.

Music

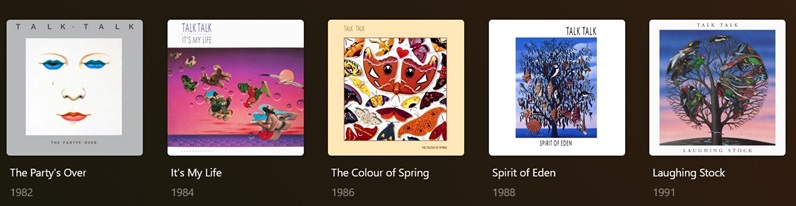

All I wanna play is Talk Talk

It’s been a grey, cold day today and I’ve been listening to Talk Talk, all five their albums in chronological order. Talk Talk always feels autumnal to me so this was the perfect day to put them on.

Now critics always go on about how different each Talk Talk album is from the next, especially the last two from the first three. And indeed, when you listen to Laughing Stock (1982)after The Party’s Over (1991), they don’t sound as if they’re made by the same band. But when you listen to them in order, you can see an evolutionary line in there, one album following logically from the previous.

The Party’s Over is very of its time, big flat drums and lots and lots of synths, but it already contains the seeds for the next two albums, It’s My Life (1984) and The Colour of Spring (1986). These two keep the big, open sound of that debut but dial back on those drums and synths. Spirit of Eden (1988) meanwhile is much more withdrawn and quiet, but its A-side follows logically from The Colour of Spring‘s B-side which already started quieting down.

If you only know the big radio hits and then stumble across those last two albums I can understand why they sound so out of left field, but in context they build up logically from those very first beginnings. Listening to them I really couldn’t tell where The Colour of Spring ended and Spirit of Eden began.

In conclusion: Mark Hollis was a genius and Talk Talk one of the best bands from the eighties.

If I Should Fall From Grace With God

Peter Mitchell nails the appeal of the Pogues:

That hauntedness is probably the most important thing about the Pogues. If their best songs have the quality that all properly miraculous songs have, of having somehow always existed and simply been plucked from the air or heaved up from a collective unconscious, it’s worth remembering that they emerge from an obsessive engagement with a folk tradition and the histories that made it – all of which are histories, more or less, of defeat.

Coincidently, If I Should Fall From Grace With God was also my introduction to the Pogues.

2000AD: a personal history

Discourse 2000 is a new project started by Tom Ewing, looking at the history of 2000AD. He explains why and how in its first installment:

I’ve wanted to write about 2000AD for years. It means a lot to me. It means a lot to most British comics readers of my age and a fair spread of years around that, I’d guess. A lot of my aesthetic sensibilities, in comics and frankly beyond them, are rooted in what 2000AD did to me at a tender age. Acquire a taste for thrill-power when your brain is young and open and it never really leaves. This blog is my attempt to do right by the comic.

Its format is simple. I’m not a historian in the archival, dates and interviews and reconciling sources sense. This is a critical history of 2000AD, in that I’m arranging its entries so they tell a roughly chronological story – but the emphasis is on criticism, which means I’m more interested in what appeared in the Prog than the details of how it got there.

But I’m interested in everything that appeared. Each entry will look at a different strip; each strip will get its own entry. I’m taking 2000AD a year at a time, aiming to cover the first 10 years at least, and long-running features with multiple stories (most obviously Judge Dredd) will get an entry for each year. But something like Inferno, which starts in 1977 and runs into 1978, will only get the one write-up. Sometimes the entries will stick closely to a discussion of the strip; sometimes they’ll range more widely. Britain in the late 70s and early 80s was a volatile, exciting place, even as it was also tacky, venal, and nasty. There’s a lot going on.

I didn’t get to 2000AD myself until a decade later, my entry point being, as it was for so many, Judge Dredd. Dredd had had a shortlived comics series in the Netherlands and I had gotten into superhero comics and he was close enough to one, right? That particular series ran for less than ten issues but did the Brian Bolland Cursed Earth saga which was mindblowing to a fourteen year old. Maybe even more important for a young metal head, Dredd had been namechecked in the liner notes for Anthrax’s Among the Living album, alongside such other late eighties comics like TMNT, The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen, Byrne’s Fantastic Four, Miller’s Daredevil, Boris the Bear and D.R. and Quinch, with Bolland, John Wagner, Ron Smith and Carlos Ezquerra also mentioned. The Anthrax boys were serious comics fans it seems and rare, knew their 2000AD. And what really fried my eighties nerdy teenage brain was this:

Anthrax wasn’t the only rock band to be inspired by Dredd of course; The Human League of all bands did their own version of I Am the Law. For me, it came at exactly the right time to drag me further into the comics rabbit hole. If a band as cool as them liked comics, liked Dredd, than comics must be cool too.

2000AD itself remained elusive to me however: it was only in 1990 or so that the local comic shop started carrying it, starting with prog 700. That was the first one I ever bought and I would continue buying it up until prog 824. In hindsight, this was one of the zine’s golden ages, with excellent new Dredd and Psi Judge Anderson stories and an influx of new talent like Garth Ennis, Philip Bond, Jamie Hewlett, Peter Milligan and John Smith. There was also the return of Grant Morrison and Zenith, one of those strips I’d only ever read about rather than had read. Reading this weekly was great, even if not every story or comic was to my liking. Every prog would have at least something interesting.

Over the decades since, 2000AD has only been an intermittent interest to me, to be sure. I haven’t read the zine since, but rather have bought the occassional collection of classic series, like Halo Jones or Strontium Dog. But at Worldcon this year I got curious again about that period in UK comics, roughly from 1988 to 1993 or so when it seemed that 2000AD might’ve brought into being a new sort of adult comics zine in Britain: Revolver, Crisis, Toxic, Blast. All sorts of earnest, mature monthly titles suddenly sprung up and seemed to have created a new market for a more grownup version of the 2000AD. Alas, all of them were gone in a year or two and it remained a pipedream, but seeing those on sale at the one comics dealer at Worldcon piqued my interest again. A lot of interesting ideas and comics were tried out in those years and much of it was first nurtured by 2000AD.

Tom Ewing’s new project therefore comes at the perfect time for me and judging by its first four released chapters, should be required reading for anybody curious about 2000AD.

The Rest Is Indeed Noise

For the past few months I’ve been mostly been listening to classical music in its broadest possible definition, everything from 17th century baroque pieces to the work of 20th century composers like Bernd Alois Zimmermann here.

Listening to his Intercomunicazione today it struck me that this is Zimmerman doing in 1967 something not too dissimilar from what bands like Throbbing Gristle, Einstürzende Neubauten or Nurse with Wound would be doing roughly a decade later, just with classic instruments rather than electronic ones. It activates the same neurons as their music in my head. A far cry perhaps from a Mozart or Beethoven or even a Mahler of Schoenberg, but even Beethoven’s Ninth was said to be deliberately unplayeable when it was published. Apparantly it’s only due to the improved skills of musicians today that we even stand a chance of hearing it in its intended form. Not that different in intent perhaps from what Zimmermann does here.