Tom Spurgeon responds to the decision of a Brussel court to allow the Tintin racism trial to go ahead. Brought by one Mbuto Mondondo a few years ago against the publishers and owners of Tintin, as he found Tintin au Congo racist and “insulting to all Congolese”. Though not much publicised in the English language comics web, you can imagine in Belgium and France feelings run high about this case,

as Tom explains:

What I hear most often from the side that thinks the case is stupid or even dangerous is that it trivializes the intent of the law for the sake of course-correcting the dissemination of art whose racism is easily understood both as racism and as a deeply unfortunate product of its time. What I hear from the other side is that the criticism of Mondondo comes from an infuriating, deeply troubling perspective that combines the willful excuse-making of the fanboy with the cold arrogance of French-language speaking people generally when it comes to any suggestion of a blind spot in national or regional character. I’m also never surprised when I meet people disgusted with both sides, questioning, say, both the authenticity of the complaint and the strangulated fashion in which the publisher tried to negotiate issues of jurisdiction.

What really isn’t in question in this dispute is that Tintin au Congo is racist, because it is so racist. It’s not just that all Black people in the story are depicted in the worst kind of racial stereotype, all thick lipped, coal black and outfitted in ridiculous clothing, but also that the story itself is incredibly patronising towards them, treating them as ignorant, superstitious lazy, emotional children unable to talk properly needing Tintin to solve their problems because they’re too feckless and thick to do it themselves, so they make him their king.

The page I scanned from my anonymous seventies or eighties edition of the 1947 version of Tintin au Congo shows one of the worst incidents in the book, after Tintin managed to derail a train, he has to goad the angry people on board it in helping him put it on the rails again, but they are more interested at first in moaning than in working, until Snowy gives the right example. And that’s in an already cleaned up version of the story; the original version was allegedly worse.

So yeah, that people get offended by this book is understandable. Herge was bone ignorant when he wrote it, writing from his prejudices and that of his audience, being published in ‘Le Petite Vingtième, the youth section of the rightwing catholic Vingtième. His next album, Tintin en Amérique is no better, not to mention Tintin au pays des Soviets. But to go so far as to start a lawsuit to get it banned?

It’s easy to be cynical about the motives of Mondondo, to see this as a media stunt, an irrelevant nuisance suit. But then again he has been pursuing this for years which seems to indicate something more is going. Similarly you can also argue that there are more important targets to go after than an eighty year old comic, but is that true?

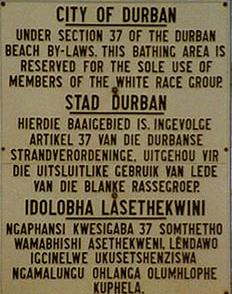

Tintin au Congo is an important comic, the true start of arguably the most succesful comics series in Europe, something that has been a part of the childhood of generations of European children sinces the early 1930ties. And in a climate that’s far more welcoming to the kind of casual racist imagery that America has long since rejected (try and googling images of Zwarte Piet for example) having such an influential comic indulge in outdated colonial attitudes is not good. Tintin au Congo‘s racism may, as Tom puts it, be “easily understood both as racism and as a deeply unfortunate product of its time”, but this is true much more for adults than for children coming to it without having the context to place the story in, accepting it at face value. I know I did, all those years ago when I first read it, just like I accepted that America was a place where Tintin could tangle with gangsters in Chicago and indians out west.

On the other hand, any sort of ban, setting apart free speech issues, does mean that an important piece of comics history is lost. Which may not be very important in the world outside comics, but it is a kind of history falsification. The attitudes Herge brought to Tintin au Congo were mainstream, widely accepted facts in Belgium about the Congo, typical of any colonising power seeing its subjects out there as wilful children that have to be lead by a loving but firm hand towards doing what’s best for them. Having Tintin au Congo as a prominent reminder of this may on balance be a good thing.

According to Het Laatste Nieuws Mondondo would also be satisfied if the book was no longer sold in the child’s section of bookstores and would be put into context through e.g. a warning about its racist elements and/or some sort of preface setting the story in its proper context. If this were to be the outcome of the trial, I wouldn’t be unhappy. Banning it complete is losing a piece of important history, not doing anything with the justified complaints of Mondondo, regardless of his personal motivations, seems wrong as well. Having it put in context seems like the best solution.