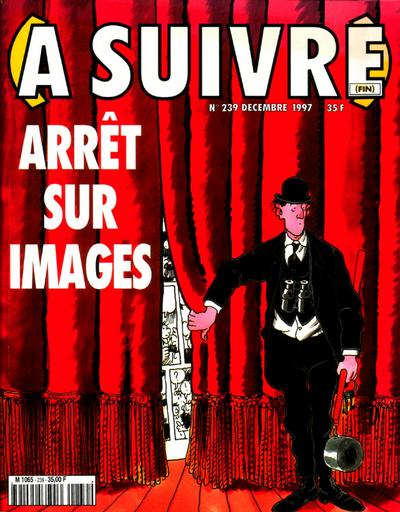

The final issue of (A Suivre) meant it was no longer to be continued, ending a twenty year tradition of publishing mature, literary comics series for people who’d outgrown the traditional magazines.

Very short recap of Franco-Belgian comics history: at the end of WWII Spirou and Tintin became the dominant comics magazines in the French language, with such luminaries like Franquin, Tillieux, Jijé, Peyo, Tibet, Graton and of course Herge among many others. In the sixties the torch was passed to the French Pilote, where a new generation of cartoonists broke through, among them the Goscinny/Uderzo due whom you may know from a little comic called Asterix. Then in the seventies, Métal hurlant, L’Écho des savanes and Fluide glacial brought a more mature edge, freed from the restrictions of the more commercially orientated older magazines.

In 1978 Casterman, for the most part a fairly traditional publisher which was actually founded at roughlt the same time as the United States (1777), thought that having their own magazine was a good idea. Through it they could promote their various series without being beholden to other publishers as well as share the cost of publication between magazine and album. They also had an audience in mind, an older audience that had grown up reading comics that wanted something more suited to their tastes, if not necessarily the avant-garde works published in Métal hurlant. Grown-up adventure stories perhaps.

(A Suivre) therefore was created as a monthly rather than weekly magazine, which would publish both complete short stories and continuing stories, but in larger chunks than the traditional two pages of the weeklies. The sort of author they were looking for can be found in that last issue: Jacques Tardi, Ted Benoît, François Bourgeon, Loustal/Paringaux, Varenne, Manara. Hugo Pratt, who Casterman had published since 1973 in French, was also a huge inspiration and contributor. These were all people who used the adventure strip genre to examine more literary concerns, more concerned sometimes with the emotional states of their characters than whether they defeated their villains.

This formula worked for some twenty years, from 1977 to 1997, with Casterman publishing successfull stories as albums sometime after they first appeared in (A Suivre). For a few years there was also a Dutch version Wordt Vervolgd, which like the French means To Be Continued. By the mid-nineties though the comics market had changed, with most readers no longer buying magazines but albums. (A Suivre) therefore was no longer sustainable and had to be cancelled. Yet for two decades it had improved and raised the overall level of the Franco-Belgian comics tradition, which is worth something at least.