Mayonaka Punch, just like Na Nare Hana Nare, is another original series done by P.A. Works airing this season. Starring Masaki, a once popular streamer who fell from grace after she punched one of her co-hosts and friends live on air. The first episode saw her stumble across an actual vampire when she went back to the abandoned hospital where she and her friends had recorded their first viral video. Said vampire thought she was the woman of her dreams (having just literally woken up from a twenty year long erotic dream starring a girl that indeed looked a lot like Masaki) so agrees to help her get a million subscribers to her new channel if she can suck her blood afterwards. The first three episodes were mostly about Masaki and her desire to make a quick success of her new vampire friends, while we got to know them as well, but it’s the forth episode I want to talk about.

This episode stars Fu, the shy, green haired vampire girl who hides behind her bangs. She had been in the background until this episode as the other four, much more manic vampires took the spotlight. Masaki, still desparate for a hook to establish her new channel on, discovers that Fuu is actually a good singer when she listens to a decades old cassette tape of her. When she tries to get Fuu to sing for her videos, Fuu refuses and gets angry, saying she doesn’t deserve to sing anymore. Through flashbacks at the start of the episode we know that she used to have a friend called Aya, with whom she would sing and record songs together. Aya wanted to go pro but of course Fuu being a vampire, this wasn’t possible for her. Once Masaki leanrs of this, she and the others attempt to track Aya down and learn that the last time she was seen was two years ago, in New York. Fuu immediately sets out there to find her, but as you may have guessed, the news is not good…

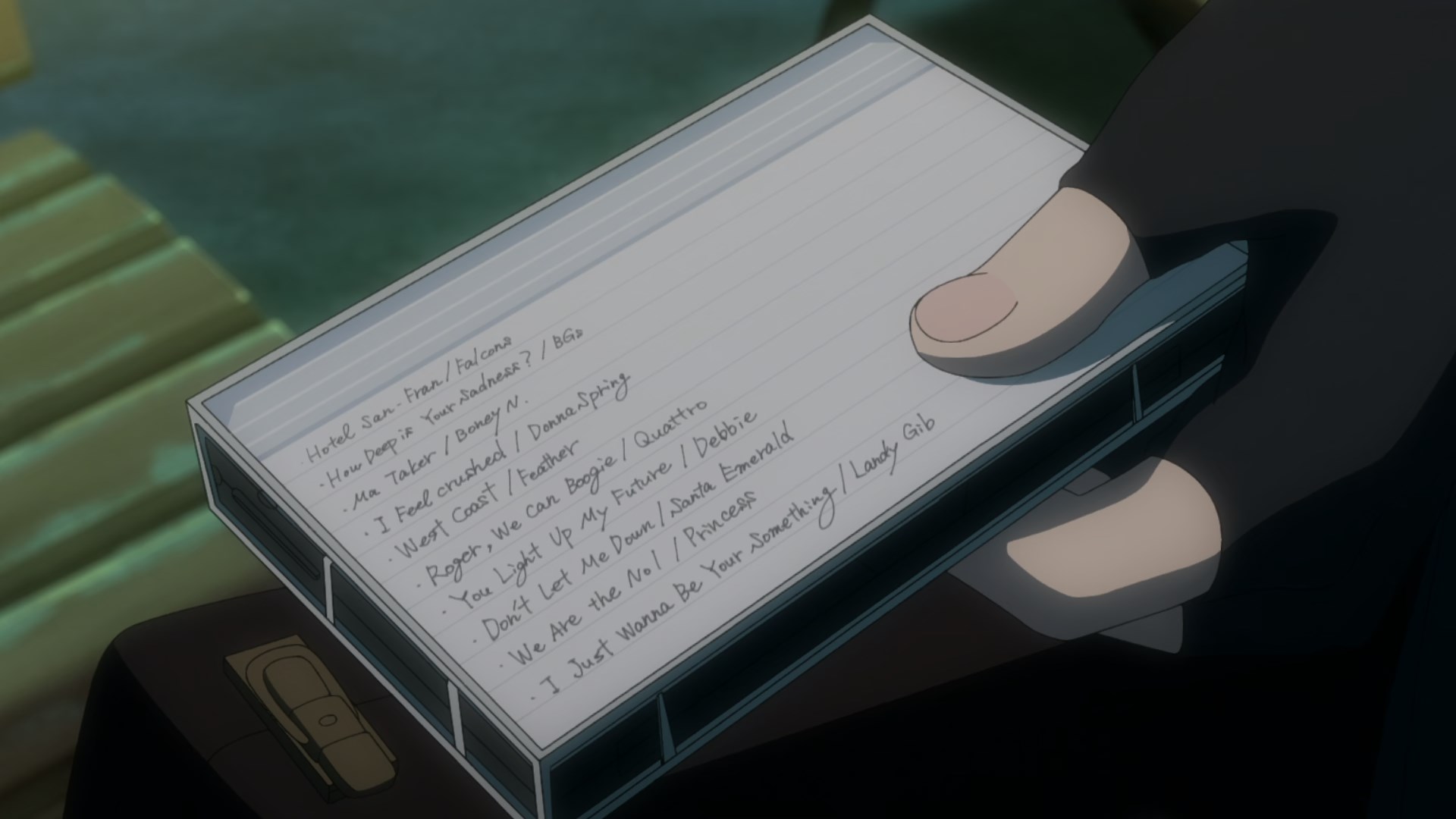

With the first three episodes having been firmly on the comedic side of things, with a large dose of slapstick thrown in, this far more serious episode hit like a brick. The pastiche titles on the mixtape Aya gave her at the start firmly show that the flashback took place somewhere in 1979 or 1980, so Aya being a teenager then meant she should be in her early sixties now. What exactly happened to her isn’t told, but this isn’t a case of the mortal friend of the immortal vampire just dying of old age. A real bittersweet episode as Fuu finds closure on the biggest regret of her life, enabling to move on and start singing again, but still with that knowledge that if only…