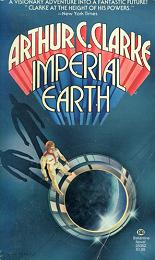

Imperial Earth

Arthur C. Clarke

305 pages

published in 1976

The last Arthur C. Clarke book I’ve read was Rendezvous with Rama back in 2002; unfortunately it was the news of his death that brought me to read another, as a private homage. I had read Imperial Earth before, in Dutch, as Machtige Aarde and liked it, though it never became a favourite. It seemed a good idea to reread this rather than one of the more obvious classic Clarke novels, to get a good idea of the strengths of Clarke’s later works. Imperial Earth was written and published in 1976 and set three hundred years later, at the United States’ quincentennial, which to be honest immediately dates it for me. On the other hand it is refreshing to read a sf novel that has the US still existing three hundred years in the future, rather than as subsumed into a world government or fallen apart into a Balkanised mess. At the very least setting the book at the quincentennial signals how much of a seventies book this is.

Imperial Earth starts on Titan where despite the harsh circumstances a flourishing colony has been established, which makes its living supplying hydrogen for interplanetary fusion rockets as the only place in the Solar System where hydrogen was abundant enough to be worthwhile to harvest and gravity light enough to be able to do it cheaply. It was through the drive and will of one man, Malcolm Makenzie, that the Titan colony became a reality and he and his family have ruled it since. That same drive meant that when it became clear he suffered from too much gene damage due to space travel to produce children the normal way, he instead let himself be cloned on Earth. His son did the same and Duncan Makenzie is the second generation of Makenzies to be born this way, now old enough to do the same himself and fortuitiously invited to the quincentennial celebrations of the birth of America.