Centauri Dreams on the increasingly many brown dwarf stars that are being found in our stellar neighbourhood and how cool they are:

In fact, it gives me pause to reflect that the focaccia I baked the night before last needed higher temperatures (500 degrees Fahrenheit) than the coolest of these brown dwarfs can supply. Most of the new objects in the Spitzer study are T dwarfs, the coolest class of brown dwarfs known, defined as being less than 1500 Kelvin (1226 degrees Celsius). One of the dwarfs in this study is cold enough that it may represent the hypothetical class called Y dwarfs, part of a classification created by a co-author of the paper, Davy Kirkpatrick (Caltech).

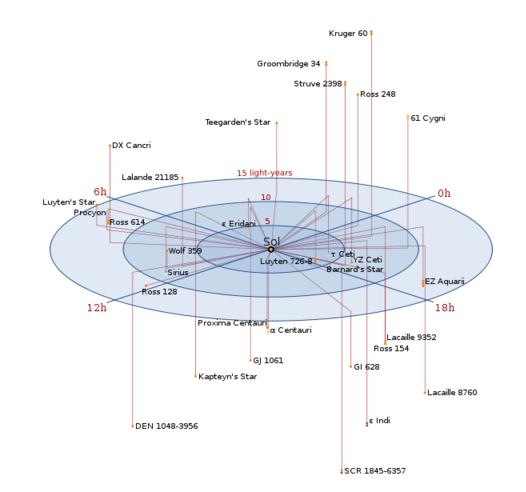

Brown dwarfs may be the most common stellar objects around as this representation shows. You wonder if brown dwarfs could have planets and if so, whether those planets could have life on them and if so, how it’s adapted to the extremely cold temperatures such planets must suffer from. Of course, from a hypothetical intelligent species arising on a planet around a brown dwarf, we ourselves would be exotic extremophilic lifeforms: imagine being able to exist at temperatures where water is a liquid!