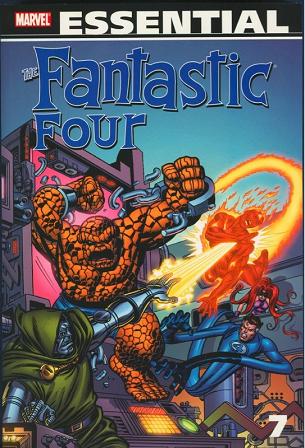

Essential Fantastic Four Vol. 07

Gerry Conway, Roy Thomas, Rich Buckler, John Buscema and friends

Reprints: Fantastic Four #138-159 and more (September 1973 – June 1975)

Get this for: The FF enter the Bronze Age — three stars

For the penultimate entry in this series we got Essential Fantastic Four Vol. 7, the first volume to feature neither Jack Kirby nor Stan Lee. Instead Gerry Conway handles writing duties for most of the run collected here, both on the regular series and on the five Giant-Size issues also included. Roy Thomas takes over from him with #156, after a fill-in issue by Len Wein. The art is taken care of by John Buscema, then Rich Buckler.

The period of The Fantastic Four collected here is one I know relatively well, having read these issues in Dutch translation years ago, buying them for a guilder at a time from a market stall. These were doublesized with cardboard covers and like the Essential collections, in black and white, so I had something of a deja vu rereading this.

At the time I first read these issues I wasn’t what you call critical of what I read: if it had superheroes and villains, especially new ones, that was good enough for me. Rereading them again it’s clear that these are not nearly of the same quality as even the worst of the Lee/Kirby collaborations; they’re quite mundane in fact, for all their non-stop action and attempts to emulate Kirby’s creativity. Lee and Kirby created the Inhumans, the Watcher, the Kree and Skrulls, the Black Panther and Wakanda and so on, basically creating the whole Marvel Universe from scratch. With Conway, we get a race of abominable snowmen, who are reverted to normal humans at the end of the story — not quite the same, is it?

Not that Gerry Conway and later Roy Thomas were bad writers, but they missed the creative spark of the Lee-Kirby collaborations. Instead both fall back on reusing established villains and soap opera to hold the reader’s interest. So we get the return of the Miracle Man, last seen in issue 3, Annihilus and Doctor Doom on the one hand and the maritial problems of Reed and Sue Richards on the other. Most stories also take more than one issue to complete, not always a good thing. It’s not all bad: I quite like that very distinctive, early seventies energy these stories have and both Conway and Thomas keep them flowing, sweeping you along with them.

On the art side there’s little to complain off, with first John Buscema and then Rich Buckler as penciler. Again, if you compare them to Kirby, both are a bit on the bland side here and certainly Buscema had and has done better elsewhere. I think that , as with the writing, the art suffers a bit from being forced into the Marvel Housestyle, trying to ape Lee and Kirby when it would’ve been better if both had followed their own paths.

Essential Fantastic Four Vol. 07 collects a low period in the Fantastic Four’s existence, when the title was in a creative slump. There are some points of interest, but they’re few and far between. For me it was an exercise in nostalgia reading these issues, going back to a time when I was much less critical of comics and could still enjoy these kind of stories for what they were.