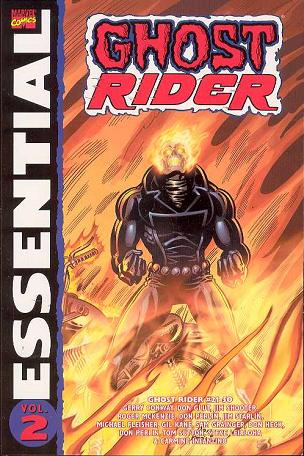

Essential Ghost Rider Vol. 2

Gerry Conway, Jim Shooter, Roger McKenzie, Michael Fleisher, Don Perlin and friends

Reprints: Ghost Rider #21-50 (December 1976 – November 1980)

Get this for: a series in search of a rationale — three stars

I wasn’t much impressed by the first volume of the Essential Ghost Rider, not in the least because the Ghost Rider, Johnny Blaze was kind of a dick. Things started to improve at the end of that volume, as Tony Isabella built up a setting and supporting cast for him and got him the trappings of a proper superhero, but one based in L.A. as opposed to New York which most of the rest of Marvel calls home. With this volume Gerry Conway is the writer and he builds on Isabella’s foundations, as does Jim Shooter who succeeds Conway after only three issues. Not for long however: with #26 Shooter sends Blaze packing, after he reveals his demonic nature to all his friends, forced into this by Doctor Druid, in an early example of his dickery.

As originally concieved, Blaze would become Ghost Rider automatically every night, which was changed by Isabella into whenever danger threatened and further refined by Conway and Shooter into something Blaze more or less controlled. Once Shooter abandons the L.A. setting however and puts Ghostie on a road trip with no specific goal, Blaze and the Ghost Rider more and more become separate identities. Roger McKenzie is the next writer having a shot at the title and he continues this trend. Under McKenzie Ghost Rider has to survive a quest for vengeance by one of his first villains, the Orb, then a Dormannu manipulated showdown with Dr Strange, followed by a hell spawned bounty hunter not so very different from himself and finally the wraith of a centuries old mutant child and his robotic motor cycle killers.

By now Ghost Rider has moved away from plain superheroics again into more occult/horror flavoured stories. With the last writer in this volume, Michael Fleisher (ignoring a fillin issue by Jim Starlin between McKenzie and Fleisher) the superheroics are entirely left behind, as the Ghost Rider becomes a pure spirit of vengeance. Each story has Blaze coming into a different town, city or village, getting involved with whatever menace is waiting for it, defeats it, then leaves. The villains he fights are either small time punks and hoods, or the local supernatural phenomenon, or both. There’s no real supporting cast, just the people Blaze meets and helps on his travels, usually involving at least one not too bad looking girl. Reading these stories in short succession you can’t help but notice how formulaic they are, though Fleisher is a good enough writer to hold your interest anyway.

The art for most of this volume is in the capable if pedestrian hands of Don Perlin, who was quite prolific in the late seventies and early eighties. His art was never spectacular or had much of his own style, but he was one of those pencilers who could be depended on to do a good job month in month out. It tells the story and that’s good enough. It’s a bit of a shame really that it was Gil Kane who opened this volume: after him almost everybody else is a disappointment. Having his art in an otherwise lackluster Essential collection is always a bonus.

Essential Ghost Rider Vol. 2 shows where the horror boom at Marvel from the early seventies ended up eventually, as just another variation on the superhero formula. There’s nothing really interesting or novel to the comics collected here.