Okay, I don’t want to begrudge anybody their Hugo rant — ghu knows I’ve written enough and in fact I’d agree with quite a bit of this criticism:

Okay, I’ve been rambling on for too long, but basically it comes down to this: most of the categories of the Hugo Awards are not fit for purpose. They are dependent on knowledge that the voter cannot have, or they make distinctions that are irrelevant to most voters, or they require comparison between items that cannot sensibly be compared. And these problems, or variations of them, extend into just about every one of the 16 categories there currently are in the Hugo Awards. It’s a systemic problem that ties in with the problems of governance and the problems of relevance that I have already highlighted.

But.

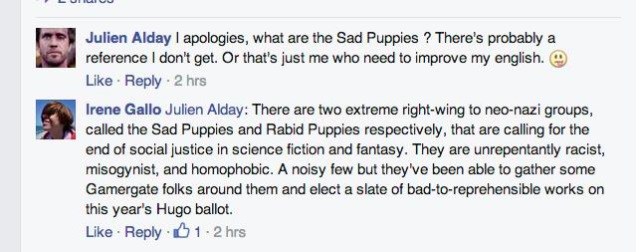

It lacks something, something that I’ve only begun to understand the importance of thanks to the slow rolling Puppy disaster of the last few years, and that’s a) a willingness to engage with the Hugos and the WSFS as it is, not as you’d want it to be and b) any sign of understanding the history behind it. If you’d design an award from the ground up, you wouldn’t have ended up with the Hugos as they are; if you had a proper board to organise it, you might end up with something like the Oscars.

But you don’t.

The Hugos are the way they are, with all their strengths and weaknesses because they’re the result of a decades long specific democratic process and the 2015 categories and rules are the fossilised remains of this process. You cannot understand the Hugos properly unless you not only know that the Best Semi-prozine category was created to shield all other fanzines from the Locus juggernaut, but also that the same sort of thing happened with the Best podcast category, the long struggle to get comics recognised properly and why there are two editorial categories and what went before that.

And not only that, you need to know the process and rules under which these changes are made, like the proposers of E Pluribus Hugo frex do seem to. You need to understand how the business meetings work as well as why and how it was established, even without Kevin Standlee to prompt you. You need to be a bit of a process nerd to be honest. (You also need to realise that much of this was designed by Americans, who seem to have a national weakness for over complicated voting systems with huge barriers to entry…)

This bone deep understanding and awareness of what is and isn’t possible given the history and current structure of WSFS and the Hugos is likely why people like Kevin Standlee might be a bit dismissive of such criticsm as well as looking overly lawyerly. That’s the risk of being an insider, you have a much better grasp on the mechanism of the system and less of an idea of what it looks like from the outside

But what you should also realise is that knowning this history and being familiar with the whole process more than likely also gives you an overwhelming sense of how fragile the whole structure is, how easy it is for a well intended proposal or rules change to damage or destroy WSFS. I see a deep fear and wariness behind that “slow and prone to complexify process, a desire to err on the side of caution, knowning how close it has come to all going kablooey.

That’s not to see genuine criticism and real change isn’t possible, but you do have to be aware of the limitations you’d be working under and know it will take more than a few blogposts to make it so. At best such a blogpost can function as a rallying cry, but you still need to do the footwork afterwards.