The first time I read Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War, it was in comics form, as a three part adaptation by Belgian writer/artist Marvano. The Forever War was Haldeman’s science fictional treatment of what he went through in the Vietnam War and was originally published in 1974; Marvano’s adaptation came out in 1988, a decade and a half later, yet it fitted the eighties like a glove. As he said in his foreword, what with the Falklands War, Grenada, Reagan talking about winning a nuclear war, a wave of right and leftwing terrorism paralysing Belgium and so on, it still seemed relevant. It seems so today too.

Which is largely due to Marvano’s own efforts, rather than Haldeman’s. Marvano had only three albums of 48 pages each to adapt a 230 page novel and like film, comics adaptations of novels need more room, rather than less. So he had to cut and choose what to keep in and what to adapt. In doing so he created the “good parts” version of Haldeman’s novel. He sharped it up, cut out the more awkward bits and kept the focus tight.

Haldeman’s original novel had two main themes. The first was the absurdity of war in general, as his hero, William Mandella, a reluctant recruit into the UN Expeditionary Force against the Taurans, the first alien race Earth had encountered and immediately went to war with, through the miracle of time dilation manages to be the only man to survive the entire war, from its start in 2010 to its end more than a millennium later, in 3177. In between the three campaigns Mandella fights in Haldeman explores his second theme, that of a soldier’s alienation on his return from fighting an unpopular war to his homeland when he realises it has changed while he remained in stasis. A popular because it was true cliche about the Vietnam War, Haldeman exagerrated these effects by his use of time dilation, having Mandella experience only a few years of war, then coming back to Earth to find decades have past and the world irrevocably changed.

Marvano could not do justice to both these themes in his adaptation and concentrated on the first. He kept the plot lines relating to the second theme as well, but compressed them greatly, spending much less time detailing the ways in which Earth changes during Mandella’s war. In Mandella’s first return to Earth for example, Marvano emphasises the way the UN bureaucracy censored his television interview over his adventures adapting to his new world, where a third of the population is now homosexual. Which is a good thing, as these are the parts of the novel that had dated the most: by making them less explicit, more generalised they keep their relevance. It’s enough to know things have changed enormously without needing to go into detail.

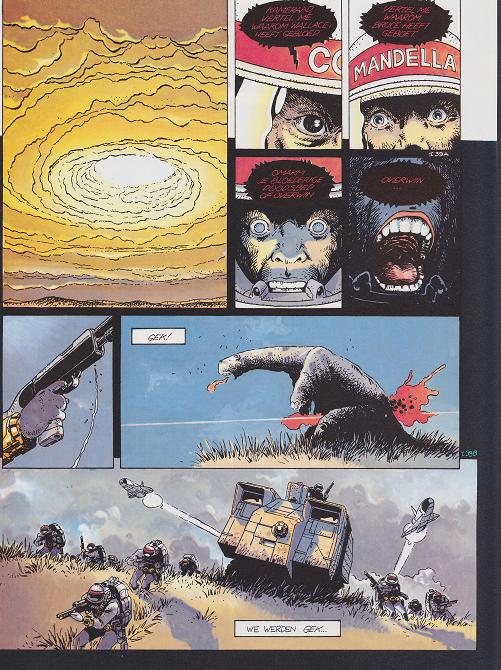

A similar pairing down is done all through the comics series and it works. What Marvano does very well, extremely well in fact for what was his first major comics project, was to let the artwork and narration speak for themselves, each conveying part of the story He lets Mandella tell the reader anything that can’t be put in pictures and let the art carry the action, not needing text to tell you what you can see in the art yourself. Mandella’s narration is almost constant, but Marvano is not afraid to silence him when needed. He’s a good artist, with a good eye for both creating realistic looking future technology and weapons, as well as for creating subtle and not so subtle facial expressions. It’s an eighties future, but still holds up today I think.

Sadly, the Forever War comic is long out of print in English, though can still be had in French or Dutch. It’s my candidate for best sf adaptation in comics ever. Marvano would do more adaptations of Haldeman novels, including The Long Habit of Living for his series Dallas Barr.