Every Wednesday, I try and showcase a female writer who is special to me for one reason or another, in an attempt to focus more attention on female sf and fantasy writers. I will limit this to writers I’ve actually read multiple books of, if only to have an excuse to link to old reviews on my booklog. This time, let’s talk about Leigh Brackett.

So I was looking through my archives to see what I’ve written about Leigh Brackett before, and I saw that each time I mentioned her I noticed that you may know her from her work writing for The Empire Strike Back. Well, can’t break tradition which is why I mentioned this again. It’s fitting that one of the best pulp science fiction authors would end up writing for the movie series whose inspiration was the sort of adventure sf Brackett wrote. Furthermore, Brackett had been an accomplished screenwriter for almost as long as she had been a science fiction writer, working on movies like The Big Sleep (1945), Rio Bravo (1959) and The Long Goodbye (1973). It’s also why her productivity as an sf writer dropped dramatically after the mid-fifties; there was better money in movies and television.

When she was writing science fiction, Leigh Brackett specialised in writing planetary romances, swashbuckling tales of derring do set on alien planets. In her case this usually Mars or Venus, back when it was still possible to think the other planets in the Solar System could be slightly different versions of Earth. Her Mars has the canals and dying civilisation, while Venus is a jungle planet full of primitive, massive reptiles. Nevertheless her worlds are not carbon copies of Edgar Rice Burroughs. Hers are much more alive, not just stage sets for transplanted western or jungle adventures: her Martians have agency.

What I like about the best of her writing is how well she can portray a mood in her stories with only a few well chosen words. In the sort of short pulp sf story she specialised there was little room for much characterisation or mood setting, so she always had to be economical, which she did very well. Her craft is also visible in her husband, Edmond Hamilton’s work. Hamilton was a true pulp dinosaur, but after he got married to Brackett in 1946, his work took a leap forward in quality…

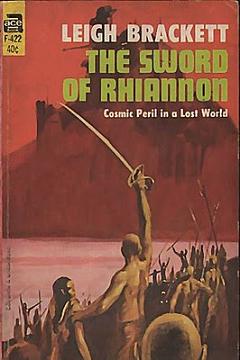

Science fantasy is that subgenre of science fiction that has all the trappings of science fiction, –aliens, other planets, blasters and aircars — but which actually read a lot like sword and sorcery in disguise, with strapping barbarian heroes fighting degenerate warlocks using superscience of an earlier age that they barely understand. It’s very romantic, not very plausible or much concerned with realistic science. Science fiction in that grand pulp tradition of Edgar Rice Burroughs. And like Burroughs had his John Carter, Brackett has Eric John Stark, the outlaw with a twenty year Moonprison sentence on his head, raised by a strange non-human tribe on Mercury, (in)famous on three planets as a barbarian and renegade, but also as a man with his own code of honour.

Science fantasy often tends towards the purple and melodramatic, but Brackett’s tone of voice here is cynical and knowing, the story told in short, clear sentences with more than a hint of hardboiled sensibility. Stark is a tarnished hero in the mold of Raymond Chandler’s worldweary detectives; you can see Humphrey Bogart playing him. Brackett describes the Mars she has invented in the same way, with a few well chosen images sketched with a minimum of words.

What sets The Sword of Rhiannon a touch above other pulp adventure stories is both Brackett’s writing and that elegiac sense of loss that comes across through it. At the end of the story Carse returns to the Mars of his own day, leaving a still living world for one that is slowly dying. He may have saved Mars from the tyranny of the Dhuvians, but its ultimate fate is still fixed…

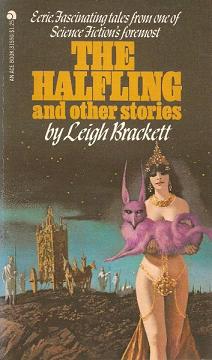

The Halfling and Other Stories:

It doesn’t help that the first two stories are basically the same. In both there’s the hardbitten protagonist falling for a mysterious beautiful alien girl who he knows is trouble yet can’t help himself but get involved with, who then turns out to be evil. Worse, in both stories this girl is shown to be representative of her race, their evil part of their biology. It’s a bit …uncomfortable… shall we say, but unfortunately these sort of assumptions are build into the kind of planetary romances Leigh Brackett wrote.