Golden Witchbreed

Mary Gentle

460 pages

published in 1983

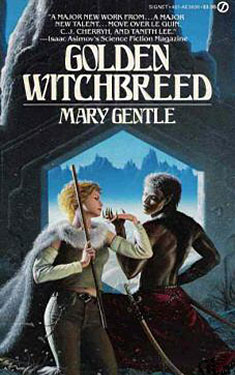

It was the beautiful Rowena cover that got my attention, a long long time ago when I was browsing the English shelves at my hometown’s library. Showing a blonde woman in jeans and fur cape, armed with a stave and linking fingers with an obviously alien six fingered man, two swords at his side. That intriqued me, it promised both adventure and romance and it got me to pick up the book and that was how I got to know Mary Gentle. I’m not sure how old I was, but I must’ve been no older than sixteen-seventeen and Golden Witchbreed was arguably the best novel of hers I could’ve started with, much more easier to get into than most of her novels would turn out to be. But though I loved it when I read it and remember it fondly, I haven’t read it since. Which was why I put it on the list for my Year of Reading Women project. I wanted to know if the book I remember was still as good as I remember.

Golden Witchbreed I remembered as a planetary romance, emphasis on romance. It starts with the cover with the two lovers holding hands. The woman on the left Lynne de Lisle Christie, envoy from Earth to the primitive, medievaloid world of Orthe, there to represent both Earth to the Ortheans and to judge Orthe on its fitness to trade and partner with. The Orthean she holds hands with therefore should be her alien lover, Falkyr. I remembered their romance as central to the plot, the circumstances in which it took place ultimately forcing Christie to go on the run and having to travel through most of the civilised lands of Orthe. Apart from that recollections were hazy.