In 2040 the research ship Event Horizon disappeared from orbit around Neptune. Now it’s 2047 and she’s back — but where has she been the past seven years?

That’s what the crew of the Lewis and Clark has to figure out. What they didn’t know until they arrived is that Event Horizon was not just a normal ship: it was designed to test a warp drive that could take it to Proxima Centauri in a day. Obviously something went wrong and when they find the Event Horizon it’s a ship without power and without crew. As they board the ship, evidence of something gone horribly wrong is quickly found: mutilated corpses, frozen blood caked on the ship’s walls, etc. Power is restored and the gravity drive that provides the warp is briefly engaged, sucking in one of the crew members who re-emergences comatose. It also triggers a shockwave that cripples the Lewis and Clark and leaves them with twenty hours to fix the ship before they run out of oxygen. All of which is bad enough without the terrible hallucinations each crew member is starting to suffer from or the weird fascination the resident scientist — also the designer of the gravity drive — has with his creation…

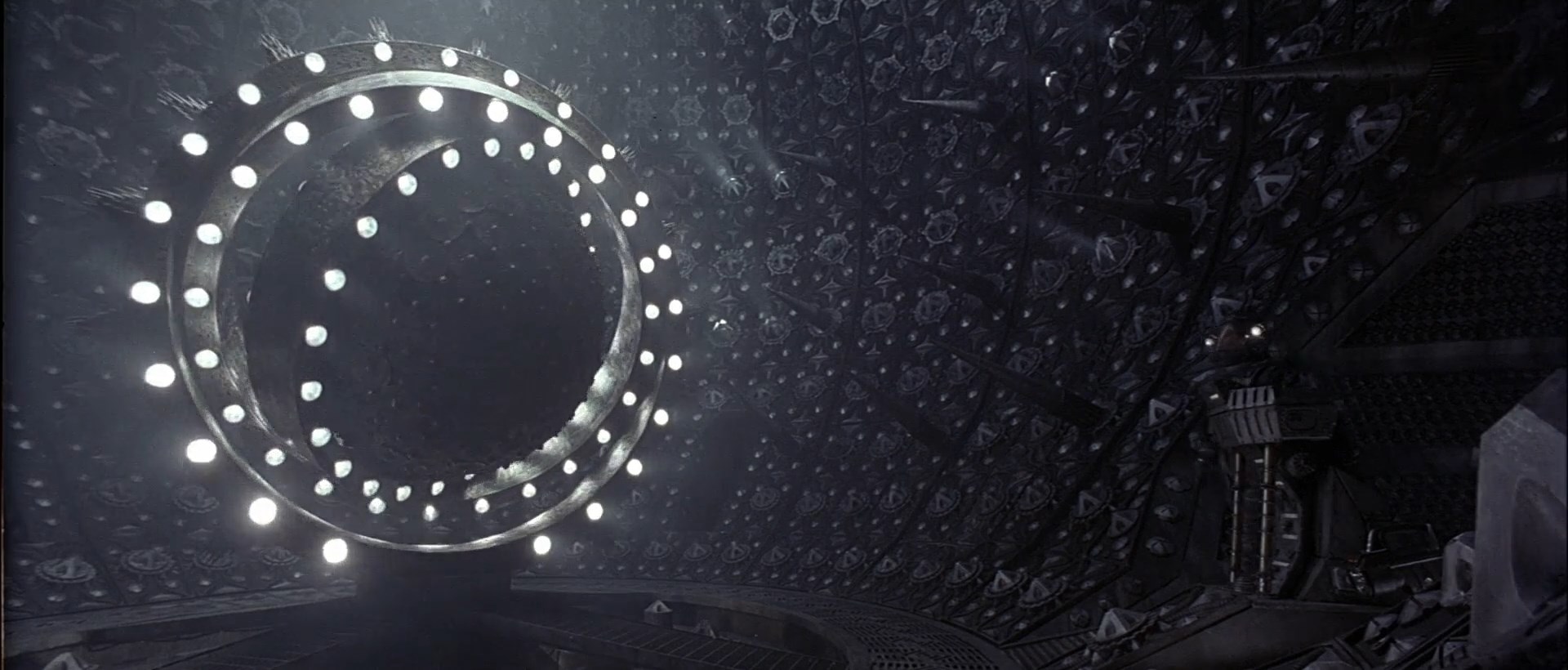

Any sane person would’ve been wary of the drive even before the hallucinations started: just look at the fucker. That gothic design just screams evil. Event Horizon is not a subtle film, squarely in that tradition of sci-fi movies warning about things we’re not meant to know. Sam Neill’s scientist character, Dr Weir, is very much in that same tradition of scientific villains driven by hubris, opposing Laurence Fishburne’s captain Miller, the commander of the Event Horizon whose first concern is for his crew’s safety. The situation deteriorates as you would expect from a horror movie following the usual pattern of crew members picked off one by one by either the ship or Dr Weir, until the last few survivors manage to escape — or do they?

I’m not the first one who made the connection between Evetn Horizon‘s gravity drive and Warhammer 40K’s treatment of warp space, far from it, but that was honestly the first thing that came into mind. Just the design of the ship is reminiscent of Warhammer 40K, let alone the idea that warp space drives you mad and is filled with demonic beings. But it’s not the only comparison that comes to mind. Hellraiser, where you can be summoned to hell if you solve a particular puzzle box, is another one, but there are also other connections to be made.

On some level you could see Event Horizon as a movie about alien contact. Something lives in warp space and ‘talked’ to the crew: it’s not its fault that contact drove them mad. Granted, Dr Weir’s actions are purely malevolent, trying to either keep the others onboard or killing them if they try to escape, btu that might just be him, not whatever entity contacted him in the first place. It might just be a Solaris situation, with an intelligence so different from ours communication is impossible, so bizarre that our minds cannot handle it. Forbidden Planet is another such movie this reminded me off, which also had some sort of creature killing off the members of an expedition to an alien planet.

A predictable, but enjoyable horror sci-fi movie.