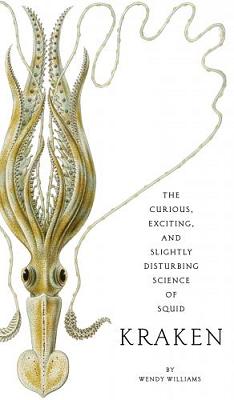

Kraken

Wendy Williams

223 pages including index

published in 2011

This was a bittersweet pleasure to read. As an homage to Sandra I wanted to read some of her favourite books and writers this year and Weny Williams’ Kraken was one of the last books she was really enthusiastic about. I had gotten it for her as part of an Amazon order in June of last year, when it still looked she was going to beat her illness and to cheer her up in hospital. Once she had read, she was keen on me to read it too to see what I thought, but I never made the time to do so, having so much else to read. It’s something I regret now, as I would’ve liked to discuss this with her, but at the same time it is nice as well to be able to read a book that reminds me so much of her. Sandra loved squids, octopuses and every kind of cephalopods; they were her favourite animals and any book on them that was any good had her favour.

And Kraken is quite good. At some twohundred pages without the index it’s not an indepth treatment of Cephalopoda, but it is a good look at what makes these creatures so fascinating. The cephalopods are invertebrates, part of the molluscs, with octopussies and squid traditionally seen as evil devil beasts that as soon drown a sailor as look at them. Yet the more we learn about them, the more fascinating they’ve become. It’s quite clear that many of them are incredibly smart, well adapted to their surroundings and with some amazing abilities — most possess chromatophores, coloured pigment cells under conscious muscular control which they can use to camouflage themselves or even “speak” with. They’re curious, they’re playful and in short, they remind us a little bit of ourselves.