Feeling under the weather enough today that I had to stay home from work and what better way to recuperate than with tomato soup and a Hayao Miyazaki movie? I hadn’t seen Kiki’s Delivery Service yet though it was released in 1989 and I’d had it in my collection for donkey ages. It seemed the perfect movie to curl up on the couch with a cat for.

Kiki is a thirteen year old girl who wants to fly in her mother’s footsteps and become an independent witch; thirteen is the traditional age for a witch to do so. So she packs her bag, takes her cat and sets out on her mother’s old broom to fly to a new team and be a witch in training for a year, during which she’ll have to discover her speciality. She ends up in the port city of Koriko, which is somewhat inspired by Stockholm but apart from that is an undetermined Europeanesque city in an unnamed country in an unspecified but slightly old fashioned looking time period. I love that aspect of Miyazaki’s work, of how here and in Howl’s Moving Castle he creates a world that’s certainly not modern, but can’t quite be pinned down to one period either.

What’s also great are all the subtle character touches: the way her cat behaves and his body language, the way Kiki herself is apprehensive going to the outside toilet in the place she’s staying in for her first night in the big town. She’d been taken in by the proprietor of a bakery at the outskirts of town, who is very friendly, but her husband is the strong and silent type and when Kiki nearly runs in to him when she’s going to the toilet and he’s starting work, it’s clear she’s uncomfortable and wants to avoid him, in a way you would be staying with a strange family for the first time.

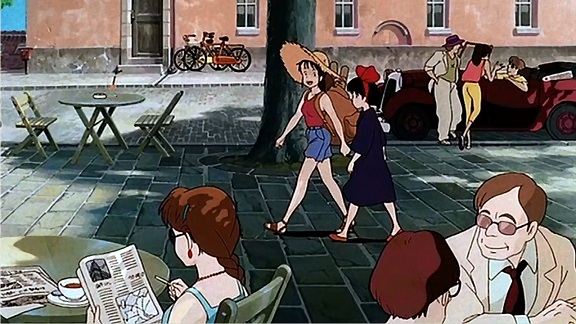

But what struck me the most watching this was how many strong and strong in different way women there were in it. It’s not just Kiki: there’s Osono the baker, who gives Kiki room and board and inspires her to start her flying delivery service. There’s Ursula, the painter, seen above, who Kiki meets on her first, not very succesful assignment and who is crucial to help her overcome her crisis of confidence in the last third of the movie. There are others, like the witch she first meets on her way to town and who gives her advice on how to spent her year in training, or the elderly customer and her servant whom Kiki helps and who help her in turn. This is a movie that passes the Bechdel test with flying colours and is full of women who help each other, rather than being rivals for a male protagonist’s affection. Not to mention men who are supportive of them, not wanting to put them down, like Osono’s husband and Kiki’s friend Tombo, who she has to safe (and does) in a genuinely tense climax.

It’s something that shouldn’t be special, should not be so noticable but it does seem sometimes like we backslid quite a lot from the eighties, in that we may be lucky to have two women in a given movie, let alone half a dozen not defined by their relationship to a man.