I’ve been at home sick since Monday last week, just as the changes Patreon was going to make to its charges became public and while I was watching PriPara season 2 it struck me that the overall story arc that season looked remarkably similar.

PriPara, for those who don’t know it, is an idol show aimed at younger girls that ran from 2014 until earlier this year, for three seasons and 140 total episodes. The first season was a relatively straightforward story of how Manaka Laala became an idol, formed her own group with two of her school friends and overcame the hostility of the head of school against PriPara and idols. What made it interesting is the concept of the series: “when the time is right, all girls receive a PriTicket, granting them access to the world of PriPara”, which is a sort of virtual reality but not quite, created by the Goddess Jewlie to make every girl (and the occasional boy) an idol. Later in the series you learn that PriPara has existed since at least the time of the Egyptian pharaohs.

In season 2 the old groups are broken up and new idols appear, as everybody competes for a change to take part in the PriPara Parade through a series of live concerts, with the winners of each getting the right to appear in the final to win that place in the Parade. A fairly typical idol tournament arc, which has new combinations of characters “fighting” together. Throughout Laala behaves according to her and PriPara’s motto: “everbody’s an idol, everybody’s a friend”.

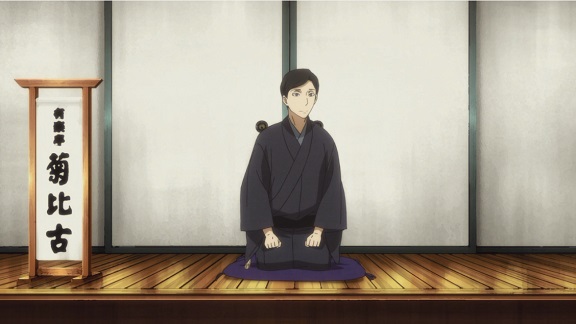

Enter Hibiki. Hibiki is diametrically opposed to Laala’s view of PriPara and is the closest the series comes to an out and out villain. A superstar in her own right, she’s introduced in episode 13 as a prince type character, a boy even; it’s only in episode 35 that she casually reveals the truth. Hibiki is a fascinating character and for more on her I refer to Andrea Ritsu’s excllent post on PriPara and Hibiki. What’s important here is that Hibiki doesn’t believe that everybody can be an idol, that everybody can be friends, but that idols should be only those with the talents for it and everybody else should be content to just watch.

Which brings me to Patreon. As you know, Bob, Patreon is a website that makes it easy to support your favourite artist or creator through monthly donations. By letting Patreon handle the billing, onerous credit card or Paypal charges are avoided, making it affordable to e.g. support a dozen creators with one or two dollar monthly contributions. This is of course also a boon for the creators themselves, as it’s of course easier to get a hundred fans to pitch in a dollar each each month than to get that one fan who’s willing to pay a hundred bucks. For smaller and part time creators Patreon has become indispensible, as it provides a steady income, lessening the pressure to find a “real” job or hunt for commercial assignments.

But then Patreon attempted to change this, by attempting to charge the patrons their transaction fees directly, rather than having them paid by the creator. So instead of a $1 donation, it would now cost you $1.38 to pledge a dollar. At first this change was justified as being necessary to cover costs, that it was too expensive for Patreon to continue doing business the old way (though this was its whole raison d’etre), but soon it turned out there was an ulterior motive. It wasn’t just costs, or Patreon wanting to gouge more money out of each transaction, but a fundamental change in its approach. Patreon had become big as a place where small and medium creators could make a living out of the donations from dozens to thousands of their fans each contributing a few bucks each month. What Patreon wanted instead was to be a place where Big Name Creators could get Superfans to drop hundreds or thousands of bucks each month. The changes therefore were a deliberate attempt to freeze out the smaller creators, though fortunately this failed and Patreon rolled them back.

Which brings me back to Hibiki’s vision for PriPara. In episode 39 she gets control over it and changes it to CelebPara. In CelebPara only already famous idols get to perform, everybody else is supposed to be content just watching the best of the best perform. And with lesser idols no longer allowed to perform, they can no longer rank up either, but then Hibiki doesn’t believe it’s possible for small time idols to become top idols anyway. Hibiki’s vision is a sterile affair, with little of the liveliness of PriPara before it, but it is superficially attractive, being able to watch top concerts by top idols all the time and no longer having to struggle yourself as an amateur. There’s a certain glitz, a certain glamour to it. Watching it while seeing the Patreon mess unfold in real time I couldn’t help but see the similarities.

Hibiki’s vision of PriPara is one of idols and consumers, where the twain shall never meet, like how Patreon was determined to have a roster of top creators and a mass of fans donating to them, rather than the messy reality of fans and creators intermixing with little distinction. More generally, it reminded me of the ways in which fandom is often co-opted and commercialised, divided in stars and punters. Too often in anime we see fans only as consumers, the image of the otaku just mindlessly buying merchandise and character goods, with only the occassional nod to the creative side of fandom. PriPara as a series is all about fans as creators: everybody is an idol. In the end, Hibiki’s vision of CelebPara is rejected and she herself comes to see how wrong she was to want it. It’s a good vision to strive for in real life fandom, not get too excited by the possibilities of commercialising your hobbies.

This is the third post in this year’s twelve days of anime challenge. Tomorrow: how Little Witch Academia fanfiction kept me sane in 2017.