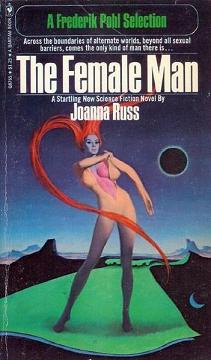

The Female Man

Joanna Russ

214 pages

published in 1975

The Female Man is the third book in my list of works by female sf authors I’ve set myself as a challenge to read this year. Of the books on the list it is the most explicitely feminist one, a cri de coeur of “second wave feminism”, a science fictional equivalent of The Feminine Mystique. Written in 1970 but only published five years later it was somewhat controversial, science fiction never having been the most enlightened genre in the first place. Reading it some thirtyfive years later it’s tempting to view it as just a historical artifact, its anger safely muted as “we know better now” and accept the equality of men and women matter of factly, its message spent as sexism is no longer an issue, with history having moved on from the bad old days in which The Female Man was written.

Bollocks of course, but seductive bollocks. The reality is that for all the progress made since The Female Man was published, its anger is not quite obsolete yet, or we wouldn’t have had the current debate about the lack of female science fiction writers in the first place. What’s more, The Female Man ill fits in this anodyne, whiggish view of history anyway. Russ is much more angry than that. She’s utterly scathing in her view of men in this novel, reducing them to one dimensional bit players: thick, macho assholes her much more intelligent heroines have to cope with. You might think this “hysterical”, “shrill”, “a not very appealing aggressiveness” but Russ is ahead of you and has included this criticism in her novel already, on page 141: “we would gladly have listened to her (they said) if only she had spoken like a lady. But they are liars and the truth is not in them.” Russ was too smart not to understand that no matter how non-threatening and “rational” The Female Man might have been written, (male) critics would still call it emotional and not worth engaging. But Russ uses her anger as a weapon and tempers it with humour and some of the angriest, bitterest scenes are also grimly witty.

The Female Man is about four women, or four versions of what could be the same woman. There’s Janet Evanston Berlin, from the all-female world of Whileaway, ten centuries in the future but not our future, who is sent on a crosstime reconnaissance of other Earths. There’s Jeaninne Dadier, a librarian in a WPA library in New York in 1969, on an Earth in which WWII never happened and the Great Depression kept grinding on, lost between her own desire grab the brass ring of marriage and children and her own knowledge/fear that this won’t make her happy either. There’s Johanna, also from 1969 but more like our own and not coincidently sharing a name with her author. And finally there’s Alice Reasoner aka Jael, from an Earth in which men and women live completely separated from each other, in a state of Cold War. It’s Jael who had brought the other three together, to recruit them and their world for the war between the sexes.

Quite obviously, each of the main characters is in a different stage of this war. Janet’s Whileaway is the dream, the utopia, where the struggle has been won for so long it has been forgotten, while Jeannine’s world is one where it still has to start and Jael’s own world is where it has come out in the open. Remains Johanna and her world, which I think we can take to be our own, where this struggle is ongoing but largely unrecognised. One example of this struggle — and of Russ’ sharp wit and sense of humoru — is the party Johanna takes Janet to incognito so she gets to witness the mating rituals of the North American male in action– boorishness, aggression, wounded pride.

Despite their symbolic value, the four Js are no cyphers, but fully realised characters and Russ spends most of the book writing their back stories, in their own voices. At the same time these four women are all clearly in essence the same woman, in different circumstances and the way Russ tells her story underscores that. Sometimes she uses the third person to talk objectively about a character and her feelings, sometimes her story is told in the first person, with viewpoints shifting quickly between characters and worlds, where every now and then it becomes impossible to figure out which “I” is actually telling a story. Frequent cutting between stories and short chapters help with this confusion and it takes effort to keep track of who is talking when — you just have to let go in the end and go with the flow.

The Female Man is a tough book, but not a hard book to read. Joanna Russ is a brilliant writer and everything in here sparkles; at times you can only sit there open mouthed with awe. It’s a tough book because of the raw anger Russ has put in it, the anguish and frustration of Jeaninne, Jael and Johanna (he character and the author both). None of these women is happy or able to do anything about their happiness, unlike the well adjusted Janet, who never had to deal with men until she started jumping worlds.

Janet is also the only one with a proper fullfilling sex life without hangups, in contrast to the patriarchy ridden other three. She’s the only one who gets to have sex in the book, with a young woman who until then was continually frustrated with the expectations her family and society expect of her to be satisfied with pretty dresses and babies. “The usual boring obligatory references to Lesbianism” as Russ again anticipates her critics. Though there is only one overt sex scene in the novel, sexuality is an important current in the book, with Janet and her healthy sexuality a rebuke to the pallocentric assumptions continuously echoed by any male character, unable to understand how anybody could have sex without a penis involved somehow. This is as much a queer book as a feminist book.

This is also a book where there are no important male characters; they’re bit players, caricatures, stereotypes but never important other than as objects for the main characters to have to work around or manipulate. As such it’s a mirror image of about ninety percent of science fiction written up till then and a fair chunk written after it as well. It’s easy not to notice this gender imbalance in ordinary novels: it’s only because it is unusual to have an all-female or largely female cast that you notice.

The Female Man itself is Johanna (Russ) who could only be taken seriously as a human when she turned herself in a man, “one of the boys” having to turn male in her thought and attitude to be able to exist on the same level as man are priviledged to do naturally, but at the loss of her female identity.

The Female Man is excellent if not free of flaws — Russ descriptions of the “changed” and “half changed” feminised men of Manland in Jael’s world is transphobic in effect if not perhaps in intent — but despite this this is a classic science fiction novel anybody interested in the genre should read.

We Who Are About To… — Joanna Russ | Martin’s Booklog

September 8, 2013 at 5:01 am[…] Who Are About To… is arguably Joanna Russ’ most famous and controversial novel after The Female Man. That novel became famous because of its outspoken feminism, still rare in science fiction at the […]

The Female Man – Joanna Russ | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased

February 4, 2017 at 2:17 pm[…] other perspectives at Couch to Moon, Martin’s Booklog, or The Ringer […]