1983: The World at the Brink

Taylor Downing

391 pages including notes and index

published in 2018

If there ever was a movie that embodied the fears about nuclear war I had living through the early eighties, just old enough to understand the concept, it has to be Threads. I turned nine that year, just old enough to start to comprehend what nuclear war would be like. We had an insane cowboy in the White House who talked about a winneable nuclear war and a series of rapidly decomposing, extremely paranoid leaders in the Kremlin. One small mistake and the world would’ve ended. And while I didn’t learn about Threads long after the cold War had ended, I really didn’t need it to have nightmares. Any mention of anything nuclear on the news was enough to set them off. It didn’t help either that pop culture at that point was saturated with nuclear war imagery.

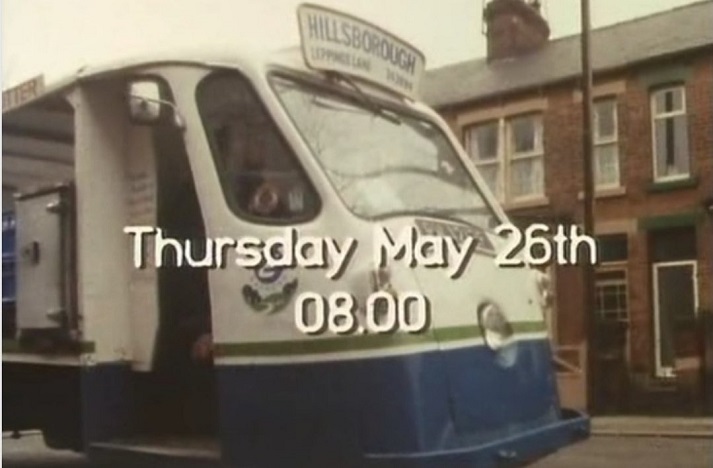

Fortunately, Threads was never broadcast in the Netherlands at that time, or I would’ve never been able to sleep ever again. Learning about it in a BBC retrospective somewhere around the turn of the millennium was traumatising enough already for the nightmares to return. That shot of the mushroom cloud going up over Sheffield with the old lady in the foreground pissing herself. That was the sort of fear and anxiety, that feeling of helplessness I grew up with in the eighties, in a country where you couldn’t pretend that you could have cool adventures fighting mutants afterwards. No, you either be dead or wishing you were. Being a sensitive kid I didn’t need to see nuclear war movies to imagine how horrible it would be. Which is why I won’t be celebrating Threads day by finally watching it.

No, I prefer to feed my nightmares through print, like with Nigel Calder’s Nuclear Nightmares which I reread a couple of years ago. As with so many people my age I know, I can’t help but occasionally pick at that scab. Especially as I got older and learned more about the realities behind my nightmares, I can’t help but want to learn more about it, to confirm my fears weren’t unfounded. 1983: The World at the Brink is very good at doing exactly that. It not only confirmed that my childhood nuclear war paranoia was justified, it showed things were so much worse than I could’ve ever imagined back then. 1983 may very well have been the most dangerous year of the entire Cold War.

The way Taylor Downing sets about showing why this is the case is by providing a chronological overview of the year and its crisises, until about two-thirds into the book we hit the ultimate crisis point, the moment civilisation could’ve ended if things had gone even slightly differently. He starts with a short explanation of the context in which these incidents took place. How the detente of the seventies had ended with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and the election of Ronald Reagan, gun-ho to take on the Evil Empire, in 1980. That with the death of Brezhnev in 1982, the head of the KGB, Andropov would be made the leader of the USSR,a man made paranoid by the Hungarian uprising of 1956, which he played a role in suppressing. Here there was a leader of the Free West who started talking about a winnable nuclear war opposite a Soviet leader deadly paranoid about attacks on his ‘socialist paradise’. Not a good combination in a time when tensions were already rising due to Afghanistan.

In 1981, while still head of the KGB, Andropov had already launched Operation RYAN, an intelligence programme aimed at determining whether the US and NATO were preparing for a nuclear first strike. By 1983 this operation was intensified as the US was starting to deploy cruise missile and Pershing II nuclear missiles to Europe as part of Reagan’s general re-armament plans. While RYAN was intended as a safety measure, its real effect was to feed Andropov’s paranoia, making him increasingly concerned that the US was planning a first strike. Reagan meanwhile, cheerfully unaware of this, was talking up plans to create a missile defence system against nuclear attacks, making America invulnerable. Regardless of the technical merits of Star Wars, even thinking about such a defence against nuclear attack was threatening the status quo of mutually assured destruction. Peace was being maintained because both sides could destroy the other completely, regardless of who shot first. There was no advantage in starting a nuclear war as long as everybody died in it. But if an increasing technological advance meant the US could defend itself, or could unleash such a devastating first strike that retaliation was impossible, that put the USSR in a dilemma. If the US was preparing a strike, the Soviets should strike immediately before the strike had even launched, or risk being caught off guard. And that was much more ripe for error than if you wait until the missiles have actually launched.

And then, in September 1983, a Korean airliner blundered into Soviet airspace, was mistaken for an American military spy plane and through a series of tragic errors, shut down with all passengers and crew killed. That immediately shut down any tentative prospect of unfreezing the Cold War. It strengthened Reagan’s opinion about the USSR being an evil empire, while it also fed Andropov’s paranoia about the country’s vulnerabilities, that an airliner had been allowed to enter sensitive airspace unchallenged. All this set the stage for Able Archer, a NATO military exercise, which simulated a Soviet invasion of West Germany culminating in a NATO nuclear strike to stop the advance. A so-called command post exercise, in which the various military headquarters were involved but not so much soldiers out in the field, the USSR was convinced it would be cover for a real first strike against it. It had take measures to reduce its vulnerability, by putting its nuclear forces on high alert, by making the preparations for a strike so that if it was necessary it could be done almost immediately. All that was needed was for Andropov to become convinced America was about to strike and give the order to strike first. And the moment that would happen came increasingly close as the NATO exercise grew in intensity.

At this point in the book Downing had thrown me deep into that paranoid mindset; my relief when the crisis passed was palpable, even knowing full well nuclear war hadn’t happened in November 1983. The rest of 1983: The World at the Brink is more cheerful, describing how both leaders walk themselves back from the abyss. How with the deaths of first Andropov and then his successor Chernenko the way was freed up for Gorbachev, a true reformer who managed to build a personal bond with Reagan, who set in motion the events that would lead to the end of the Cold War as well as the Soviet Union. Even more than three decades onwards, it’s still a miracle such a vast and powerful empire could be dissolved mostly peacefully, that we didn’t all die in nuclear shock waves in November 1983.

If you’re my generation, this book then is the confirmation of all the old bad dreams you had back then. If you’re too young to have lived through it yourself, a good look back a period where all this was normal.

No Comments