Genius, Isolated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth

Dean Mullaney & Bruce Canwell

324 pages

published in 2011

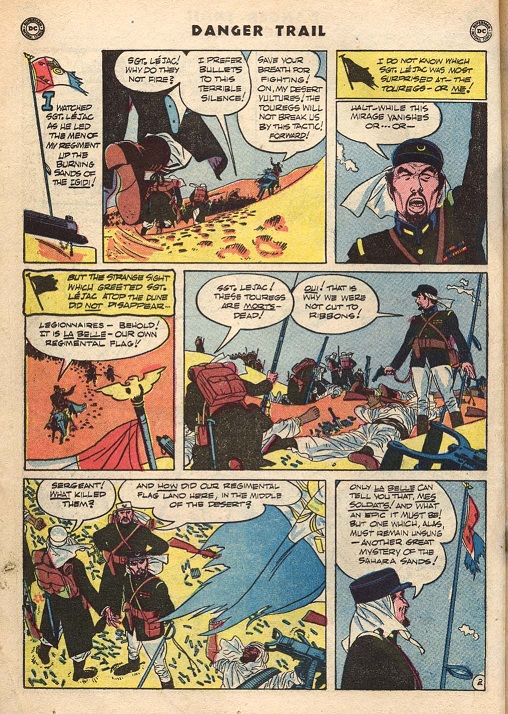

If you’re not a hardcore comics nerd you’ve probably never heard of Alex Toth, one of the greatest cartooning geniuses American comics have ever seen. That’s because he never really had a comics series or character that he made his own, but instead had his art scattered over hundreds of seperate assignments for dozens of publishers, often wasted on formulaic, throwaway stories. His true genius lay in his approach to the art form, the way he stripped down cartooning to its essentials, never putting down one more line than was needed. Once you see his artwork you can understand why he’s so revered by his peers, a true “artists’ artist”, but first you needed to find his artwork, which has long been difficult to find other than by hunting through back issue bins.

This has changed in the last decade or so, fortunately, as the American comics field in general has become more aware and interested in its heritage, leading to a flood of high quality reprint projects as well as art books/biographies focusing on individual artists. Toth has had some attention paid to him before, but with Genius, Isolated: The Life and Art of Alex Toth, the first of a trilogy of books devoted to Toth’s life and career there finally is a book that does true justice to Toth’s genius.