On 25 February 1941, less than a year into the nazi occupation of the Netherlands, communist union leaders called for a general strike against the increasing persecution of the Jews. The resulting two day strike in Amsterdam and various other cities in North Holland, the February Strike was the first and only massive public protest against the persecution of the Jews in occupied Europe.

Amsterdam had long been a Jewish city, with a large Jewish neighbourhood in the centre and south of the city. Even before the Germans had conquered Holland, there had been clashes between Jewish people and sympathisers against the indigeneous Dutch fascists of the NSB, the National-Socialist Movement. After the occupation the latter became bolder and started systematically harassing Jewish Amsterdammers, who in turn defended themselves, often with the help of their non-Jewish neighbours and friends. This culminated in a street battle at Waterlooplein on 11 February, when a group of NSB thugs attacking Jewish owned businesses were themselves attacked by a communist strike team of Jewish and non-Jewish residents. As the smoke cleared, one NSB man was left mortally wounded, who died on the 14th.

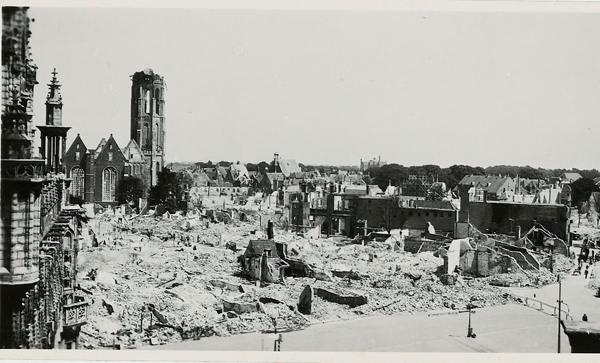

This incident, as well as similar one when the German SD tried to raid a Jewish-owned icecream parlor and got their asses kicked, was the excuse the nazis needed to institute the first razzias, driving together several hundred Jewish men, beating and torturing them, before sending them off to the concentration camps. This razzia took place on February 23-24, with the communist appeal for a general strike following the next morning.

Though the strike in the end was largely futile, it did serve to rip the mask off the nazi occupier. After its brutal repression it was no longer possible to believe things could continue as usual. In Amsterdam the strike is still remembered each year with a march past the Dokwerker, the statue created in remembrance of the strike in 1951, located on the Jonas Daniel Meijerplein, a centre of the old Jewish neighbourhood.

What makes the Februarystrike special is not just that it was such a public act of resistance, but that it was organised by the Dutch communist party and the communist aligned union, at a time when Nazi Germany and the USSR were still nominally allies. It was also one of the few public acts of resistance in the Netherlands, where the majority of the population not unnaturally just tried to keep their head down, while unfortunately the civil administration and bureaucracy went much to far along in their normal patterns of obedience to authority, even when in service to evil. It’s a proud moment for the Dutch left, one of those times when it took a principled stand, even if an ultimately futile stand, where it led the ordinary people of Amsterdam in, even if for just two days, resisting the deportation of their Jewish neighbours.