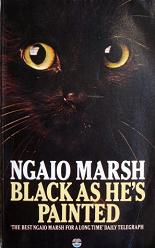

Black as He's Painted

Ngaio Marsh

221 pages

published in 1974

If my girlfriend hadn't insisted on me reading a passage of this, I would've never have read Black as He's Painted, or any other Ngaio Marsh novel for that matter. My mum, a big fan of the British cozy detective genre, used to read a lot of Ngaio Marsh, but while I did dip into her Agatha Christie collection I never felt the urge to sample the Ngaios. Until I read the passage in question that is. You see, as so many other bookworms, I'm a sucker for cats and fictional threatments of cats; there's after all nothing as cozy as curling up on the couch with a cat and a book. And Ngaoi Marsh managed to sketch such a convincing and sweet portrait of a cat in the paragraph I was "forced" to read that I immediately wanted to read more.

What had grabbed my attention was the opening of the story. Somewhat unhappily retired ex-Foreign Office civil servant Samuel Whipplestone is going out for a morning constitutional, when he encounters a little cat almost run over by a car. "In a flash it gave a great spring and was on Mr Whipplestone's chest, clinging with its small paws and --incredibly-- purring. He had been told a dying cat willsometimes purr. It had blue eyes. The tip of its tail for about two inches was snow white but the rest of its person was perfectly black. He had no particular antipathy against cats." That's so charmingly written and nicely observed I couldn't help but read the rest of the book when I was home with the flu and in need of something light to read.

Ngaio Marsh can best be compared to Agatha Christie; she started writing detective novels slightly later than Christie and having an equally long career, her last novel appearing in 1982. Each of her novels featured the same hero, Roderick Alleyn, gentleman-detective working for the Criminal Investigation Department of the Metropolitian police. Black as He's Painted is a late entry in the series, published in 1974, very much a classic English whodunnit. Now this is a genre that pretty much had its golden age before the war and to read one set in 1974 is interesting. The plot on the one hand revolves around the attempt to murder a president of newly decolonialised country, a throroughly "modern" twist, but on the other much of the writing and dialogue could've just as easily have come from a thirties detective thriller. There's one particular aspect of the story that is not just oldfashioned, but somewhat embarassing. As said, the plot revolves around the attempt to kill the president of the African country Ng'ombwana, coincidentally an old schoolmate of Alleyn's, and some of the language used to describe him and his people is somewhat ... unfortunate. Nothing consciously racist, but there's some mention of the essential nature of "the Negro" and such.

Roderick Alleyn is involved with the security of the Ng'ombwanian president, thanks to his old school ties. Said president, or Boomer as he insists Alleyn calls him is somewhat careless with his security, convinced he cannot be killed. Much of Alleyn and his colleagues' security worries revolve around the big party the president will throw at the Ng'ombwanian embassy, a worry that's fully justified when despite all their precaution some assassin still manages to kill the ambassador with a ceremonial spear. It's now up to Alleyn to find out who killed the ambassador before the killer geta another chance to attack what was obviously his real target, the president himself.

Meanwhile much of the novel is little or not at all concerned with Ng'ombwana, its president or the murder attempt at all, as we follow Mr Whipplestone while he finds a flat in a cozy London neighbourhood, (coincidentally located near the embassy), comes into contact with the little stray cat again and takes her into his new home. At the same time he becomes gradually aware of the strange going-ons of his neighbours, including the man he bought the flat from who still lives in his basement, the old couple he has retained as his house help as wel as the grossly fat brother and sister who run the nearby pottery which specialises in making clay pigs. Of course this is all related to the Ng'ombwanian doings, but it's neither Whipplestone nor Alleyn that provides the one clue that hangs it all together. No, it's Lucy Lockett, the little stray cat that manages to do so...

What I liked anbout this was not so much the detective story itself, which was okay, but the gentle wit with which Marsh describes Mr Whipplestone, his cat and his involvement with solving the mystery. She manages to portray the absurdity and humour of it without making Mr Whipplestone into a figure of ridicule. It makes for a quite amusing read.