The British Character

Pont

120 pages

published in 1938

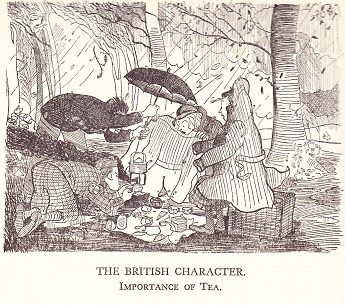

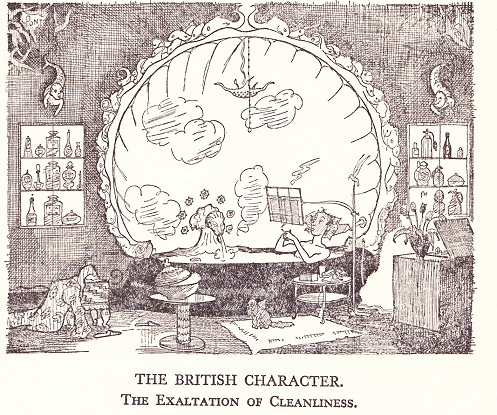

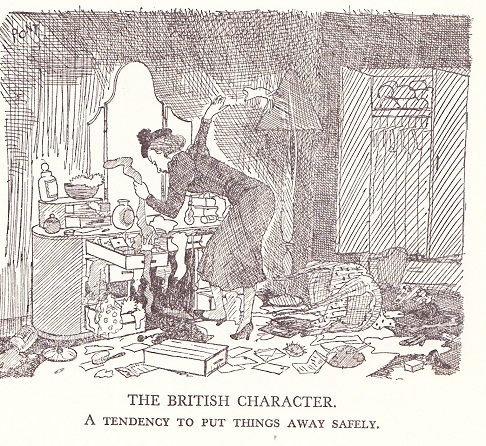

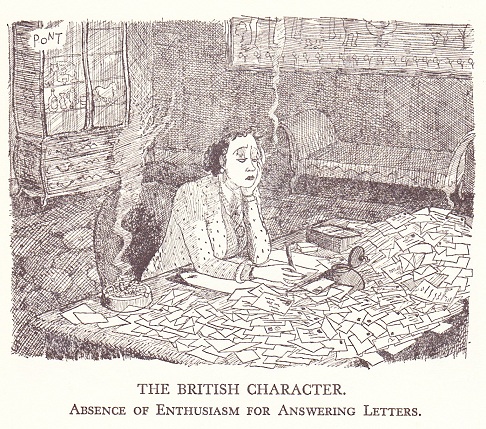

It must’ve been a decade ago that Sandra found this book in a secondhand bookstore in Middelburg. She liked the cartoons, but since she had read it by the time I was done browsing, she didn’t think it worth buying. I disagreed and bought it for her as a present. She took it back to Plymouth with her, brought it back over when we started living together and today my eye fell on it when I was looking for something to read from among her books. It reminded me of how she liked several of the cartoons enough to make high quality copies of them, to hang on our walls. She recognised herself in them, some essential quirks of the British character she also possessed. Looking at these cartoons now I can’t help but seen Sandra in them.

Pont is a pseudonym for Graham Laidler, a cartoonist who mainly worked for Punch, starting his “British Character” series there in 1936, with this collection first having been published two years later, and multiple times since. He himself had only a short time to enjoy his success, as he died in 1940 at age thirtytwo. He had been ill a long time, his sickness being the reason he turned to cartooning in the first place, rather than the architectorial drawing he had been trained for. Though his cartoons are very much of his time, they do touch on universal aspects of the British character.

But therein lies a paradox because, as Alan Coren indicates in his introduction to this edition, the people Pont depicts in his cartoons are stereotypes, hoary even at the time he first put them to paper. His character studies are largely limited to that of one class only, draw a caricature of the upper classes as existing in the English popular imagination, if not quite in reality. The people in them, in the midst of the great depression do not have jobs to worry about, or anything else really. Pont’s humour lies in gently mocking their pretensions, their idiosyncrasies and petty concerns. There is no anger or judgment in them.

To be honest, many of the examples of this socalled British character are far more universal than that, familiar to culturally middle class people — like myself– all over the world. Yet, when looked at in total, there is a Britishness, a limited sort of Britishness perhaps, but a Britishness still, that speaks out of these cartoons. A very radio 4 sort of Britishness.

As you can see from the examples, they’re all done in pen ink, with a lot of fiddly dark lines and lots and lots of details, yet still with a certain looseness in the lines. The pictures all are a bit on the gloomy side, of course matching the stereotypical weather in the British isles. They’re quite lovely in their way. Almost every page in the book also has little side sketches, in a much looser style. So if you find a copy of this book, get it.