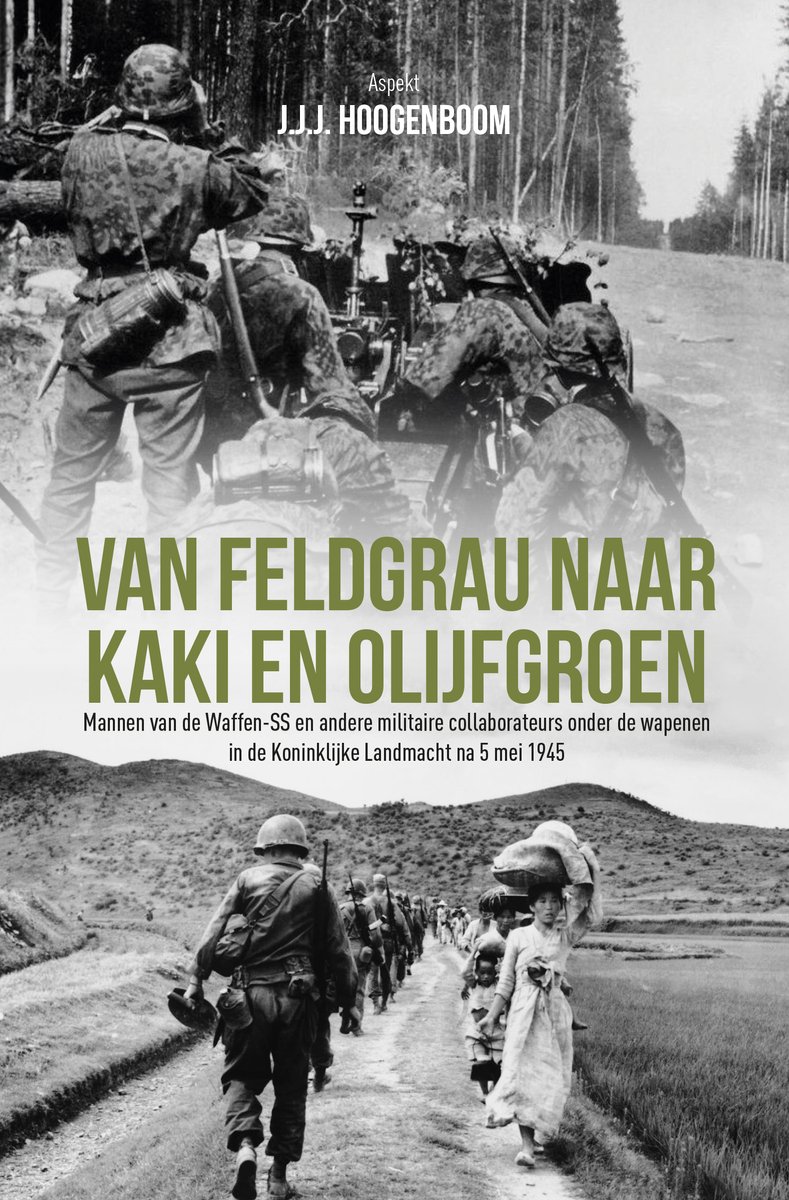

Van Feldgrau naar Kaki en Olijfgroen

J.J.J Hoogeboom

201 pages including notes and index

published in 2023

It’s a sad fact that during World War II many more men served in the German feldgrau than they did in the Allied khaki or olive green uniform; estimations ranger from roughly 25,000 to over 50,000, mostly volunteers. Most notoriously these men fought in the various Dutch Waffen-SS units, but others also served in the Luftwaffe, Kriegsmarine, Wehrmacht and various local auxiliary German army units. Post-war all these people should have lost their Dutch citizenship and civil rights for serving in a foreign military at war with the Netherlands. This would’ve included being eligible for military service, yet both during the Indonesian decolonisation wars and in Korea, there were examples of ex-Waffen-SS volunteers and others fighting on the Dutch side.

How was this possible? Did these men just slip through the net or did the Dutch military know their histories? And if so, were they deliberately recruited for their aupposed military prowess? Was there an element of (unofficial) rehabilitation going on perhaps? And how were these men treated once their past became known to their comrades and the military as a whole? Were they discriminated against or were they valued for what they brought into battle? These are the questions Hoogeboom tries to answer in this short book. He does that largely based on three different sources: autobiographies where available, the archives of the special prosecution service that processed the men who served in the German army and the information the Dutch army itself had about those who served for them. Together these three sources give an insight into the careers and motivations of some of these men. What this book is therefore is a selection of case histories, Which Hoogeboom then puts into context. He looks at how these men got to serve again, whether or not their past was known and how they were treated during their service.

The tentative conclusion he draws is that there was no evidence of any official policy to recruit these volunteers, neither for their supposed prowess in warfare nor as a means to rehabilitate them. Furthermore, that there’s little to no evidence of any special treatment of these people while in service, either positive or negative.

That these men were able to serve is due to a number of elements. First is the lack of coordination between the armed services and the offices responsible for the prosecution of war volunteers. Quite a few managed to enlist as volunteers for service in Indonesia and Korea because the army didn’t know their past. Others were drafted even though they should’ve been ineligible. Second, some volunteers, especially younger ones, were treated more lenient than the law proscribed. Depending on their circumstances they kept the right to serve in the army and therefore were called up legitimately. Third, the prosecution against some was not yet started or only finished after they had been drafted or had volunteered. Finally, as the war years started to recede in memory, the zeal to prosecute these men abated; some escaped prosecution altogether.

Their treatment in service differed too depending on circumstances. There were no official policies to discriminate against them or even remove them from service once their past became known. Some were send back home from Indonesia on request by the prosecution; others were kept by their commanders requesting so. A few were harassed and bullied by their comrades once their status became public, but most seemed to have either managed to keep it hidden or were treated no different once it became known.

An interesting book. I knew already that ex-Nazi sympathisers had served in Indonesia, but I would’ve guessed there would’ve been some from of semi-official government policy to recruit them for this dirty war. What instead seems to have happened is that only accidentally these men managed to serve, in low enough numbers that it’s plausible that this was all accidental. This wasn’t anything like the rehabilitation of Nazi commanders and officers that happened in the 1950ties in West-Germany, to provide a cadre for the newly established Bundeswehr.