As always I will do a post looking at the statistics of my reading habits this year in early January, over at Wis[s]e Words, but for now I’d like to lift out the books that stood out the most for me in 2014, in no particular order.

The Martian was one of the books with a lot of buzz behind it this year. Originally self published in 2011, it was picked up by a mainstream publisher (Random House) and rereleased with some alterations. It’s, with one exeception, the most heartland science fiction novel I’ve read this year, set smack in the heart of the genre. There have been other novels about astronauts losts on Mars before, other Robisonades. but the ones I’ve read tended to be dull and badly written. The Martian is the first one that had the same excitement as Robinson Crusoe offered in finding clever solutions to how to survive a hostile climate, but without devolving into wish fullfilment like the latter part of Crusoe did. Weir also doesn’t fall into the trap of making his stranded astronaut a Heinleinesque superman able to save himself entirely true his own efforts; instead it does take the full resources of NASA to save him.

In August I went to my first Worldcon, in London, which left me buzzing with excitement and a renewed interest in science fiction and fantasy fandom. It also spurred me on to get back into reading Dutch language fantastika, so I started off following various Dutch SFF people on Twitter, as you do. It was thanks to this that I got to know about Esther Scherpenisse’s Ter Ziele, a chapbook collection of two short novellas. The first story in particular hit me, dealing as it does with death, grief and letting go. It’s no surprise it won the main Dutch prize for science fiction/fantasy, the Paul Harlandprijs. I hope Esther Scherpenisse will write and publish more before long.

Ann leckie’s Ancillary Justice was one of the best if not the best science fiction novels I’d read last year, so my expectations for the sequel, Ancillary Sword were high. Leckie didn’t disappoint me. Paradoxically it both took place on a smaller stage than the previous novel and concerned itself with bigger matters. Most of Ancillary Justice revolved around Breq’s struggle to come to grips with her own identity and her quest for vengeance, her inner turmoil, but Ancillary Sword has those struggles if not entirely resolved, so much so that she’s in full control here. And whereas the focus of the original novel, thanks to its novel use of pronouns, was mainly on gender, here it is on the impact of colonialism, something science fiction as a genre direly needs to come to grips with. Too often after all it views things from the perspective of empire, rather than its victims; Leckie firmly reverses this.

Corinne Duyvis is another Dutch SFF writer, but one who writes in English. Otherbound is her début novel, a young adult fantasy. What sets it apart from the hundreds of other young adult fantasies are several things. First, there’s the ingenious concept of the protagonist, Nolan, being forced to live somebody else’s life, see through a stranger’s eyes, every time he closes his. Second, Duyvis makes this into a disability more than a superpower. If every time you blink you see through somebody else’s eyes, it’s bound to distract you from the real world. And that has consequences. It’s not the only way Otherbound deals with disability; all three main characters are bound together by their disabilities, their lives interwoven because of it. Third, she has also seriously thought about the consent issues of being able to share someone’s life so intimately. And she manages to do all this and write a gripping adventure story too.

I read Hurley’s first novel, Gods War, last year and that had been a good if flawed novel. The Mirror Empire is a cut above it. Hurley’s first venture into fantasy, it’s one of the novels, with Otherbound and Ancillary Sword that immediately made it on my Hugo shortlist for next year. In some ways it is a traditional epic fantasy, complete with a Big Bad that needs to be defeated, but what makes it special is its worldbuilding. The world of The Mirror Empire is one of the more fully realised, interesting and novel I’ve read in a long time and she manages it without “the great clomping foot of nerdism” stomping down on the story. Hurley supported The Mirror Empire with a promotional blog tour which is also worth reading to learn more about the background to which it was written and which explains some of her choices.

The Steerswoman series I knew about from other fans raving about it since the mid-nineties at the very least, but I never encountered the books in the wild, until James Nicoll linked to Rosemary Kirstein’s post offering the ebooks for sale. So inbetween walking from one panel to another at Loncon3, I bought the entire series. I was glad I did. What at a first glance looks like fantasy and starts out feeling like a standard if well written fantasy quest story, morphs gradually into the hardest science fiction series I’ve ever written. Because what you have here is a woman finding out the truth about the world she lives in through deduction and induction, through doing thought experiments and practical confirmation of them, without ever cheating, without being fed clues by better informed characters, without using magical technology or jumping to conclusions she shouldn’t be able to make. It’s a brilliant series too little known because for various reasons it took Kirstein over three decades to write the first four books of it and it’s still not finished. But don’t let that stop you: each book stands on its own and each is better than the last.

Question: what are the two places man will never reach? Answer: the heart of the sun and page 100 of Dhalgren. An old joke, but one that indicates Dhalgren‘s reputation as a difficult book. Which didn’t stop it from being one of science fiction’s first runaway bestsellers. Personally I didn’t find it that difficult to read, just long, because I just let myself flow along Delany’s narrative. If you go looking for a proper, standard sf, story, you won’t find it here. But it is about cities and independence and queerness and the gloriousness of our bodies, ourselves and all sorts of weird seventies shit. This is one of those books that are hard to review or recap, require some investment of time and effort to get the most out of it, but do reward you if you do so. Delany is such a good writer that I wouldn’t mind reading his interpretation of the Manhattan phonebook, as long as he keeps off the booger sex.

I also read Nnedi Okorafor’s Who Fears Death this year, but Lagoon was the better book, another Hugo candidate for me. Written out of frustration with the South African sf movie District 9, this is her version of an alien invasion, set in Lagos, Nigeria. That setting already sets it apart from the ordinary run of invasion stories, usually set in the States or sometimes Europe. But there’s also Okorafor’s unapologetic use of Nigerian English rather than “standard” English. For somebody like me not used to it, this made it slightly more difficult to read at times, but no more so than when some fantasy writer has put made up Elfish words in his fantasy. Then there’s the genre breaking Okorafor cheerfully commits here as well, as one chapter frex is told from the perspective of a spider trying to cross a tarmac road, a self aware and evil tarmac road looking for new victims to devour…

Zero Sum Game is S L Huang’s début novel, a fast paced technothriller, which I only discovered because of her post about last year’s SFWA controversies. That got me reading her blog, curious for her novel, so I bought it when it came out. What I most liked about the book was its heroine, Cas Russell, a math savant who can e.g. calculate the paths of a stream of bullets shot out by a semi-automatic in realtime quickly enough to dodge them all. If you think too much about this power it gets ridiculous, but Huang moves the action quickly enough to not give you the chance to do so. Cas is also, as becomes clear quickly, somewhat of a damaged individual, somebody with no sense of morality but not a sociopath, who has to rely on other people’s sense of what’s right and wrong, which doesn’t always end up well. Currently I’m reading the sequel, Half Life, coming out soon. Expect a review in early January.

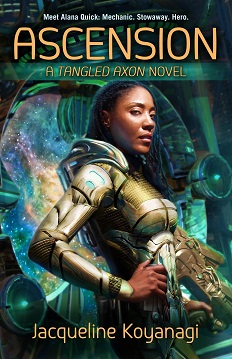

Jacqueline Koyanagi’s Ascension was a book I completely discovered by accident, on the sales rack of my favourite Amsterdam bookstore. What pulled me to it was the woman on the cover, as black women don’t often feature on sf covers, not even when they are the protagonist. And it turned out this was the protagonist, a lesbian, disabled woman of colour working as a starship engineer in a dead end job in the middle of a depression caused by a new technology that makes starships almost obsolete. This is a book about sibling rivalry, love, both romantically and otherwise and the difficulties of living true to your own life when you’re poor and almost powerless. It’s also about making choices and having the courage to stand behind them. It’s a brilliant novel, one that should’ve been a contender for the Hugo and Nebula Awards together with Ancillary Justice, but which sadly didn’t get the buzz that book got.

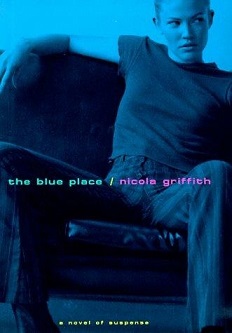

Finally, I need to mention two of the books I found the hardest to read this year, Nicola Griffith’s The Blue Place and Stay, the first two novels in a crime thriller trilogy. What made it hard for me was that these books revolved around a death, a death I saw coming throughout The Blue Place and hoping Griffith would find a way to avoid it, while Stay deals with the fallout with that murder. The grief and sorrow in the latter were so real that I had to set it aside the first time I read it, in August, because it reminded me too much of my own loss, the death of my wife three years ago. But if it was hgard for me to read, it was harder for Nicola Griffith to write, twelve years after her little sister died, with her older sister dying through it. It’s no wonder it caught grief and sorrow so well.

Other books I could mention here as well: Sarah Tolmie’s The Stone Boatmen, for me another Hugo candidate. Jo Walton’s What Makes This Book so Great, an enthusiastic anthology of book reviews. Fly by Wire, William Langewiesche’s great explenation of just why captain Sullenberger could put down his Airbus 320 down safely on the Hudson after being hit by a goose. A Stranger in Olondria by Sofia Samatar and Three Parts Dead by Max Gladstone, both read for the John Campbell Award, both very good in their own way fantasy stories. Tobias Buckell’s Hurricane Fever a great near future technothriller romp. Seanan McGuire’s Velveteen vs the Junior Super Patriots/The Multiverse: maniac superhero fanfic that hits all the feels. Aliette de Bodard’s On a Red Station Drifting: family orientated flawed but interesting space opera. N. K. Jemisin’s Dreamblood duology: Egyptian inspired, but not derivative fantasy. Richard Penn’s The Dark Colony: a near future, non cheating hard science fiction police procedural set in the Solar System. Oh, and of course there’s all the Norton I read this year, none of which disappointed.