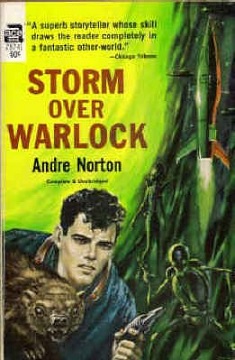

Storm over Warlock

Andre Norton

192 pages

published in 1960

So I was reading the first page and thought, hmmm, Shann Lantee, I’m sure I’ve read that name before. And yes, it turned out I should’ve read this before I read Ordeal in Otherwhere. It’s a measure of Norton’s writing skill that despite reading these in the exact wrong order, they weren’t spoiled. It helped of course that, unlike in the case of Exiles of the Stars, these were separate stories just set on the same planet; there wasn’t the need to have read this before reading Ordeal in Otherwhere. You do get a few hints that there is a larger backstory, but you get that anyway with Norton. There’s always the sense that her heroes are having their adventures as part of a much larger, largely unknown universe.

In Shann Lantee’s case, his adventure begins when the survey camp on Warlock he’s the most junior member of, is attacked by the Throg and before you can say wild thing, everybody in it is dead, apart from him and the escaped wolverines he set out to catch. Now he’s alone on a hostile planet with an even more hostile occupation force he has to evade to keep safe. He has no plan, nothing else but a will to survive and hopefully get a chance to revenge himself on the alien Throg, until fate intervenes in the shape of Ragnar Thorvald, a giant of the Scout service. Ragnar was away when the camp was attacked and his scout ship runs into an ambush when her returns, which Shann witnesses. They team up and Ragnar has a plan. They need to head to the coast, not the mountains as Shann intended. Why though he cannot or does not want to say.

Until about halfway through the story, this is all about the two of them surviving the dangers of Warlock while keeping out of reach of the Throg, but then things start happening. Having landed on a small island away from the coast Ragnar starts to behave oddly, finally leaving Shann stranded on his own. When he himself starts to sabotage his own attempts to leave, he starts to suspect that some alien intelligence is plotting against him and he sets a trap.

Which is how he makes first contact with the Wyvern, the dream manipulating witch women I already knew from Ordeal in Otherwhere. Here they’re described as reptilian but humanoid women, strange but not repulsive. Most of Norton’s aliens so far have been humanoids, which has never been explained as far as I know, just one of those standard tropes of sixties science fiction.

Shann now has to win the trust of the Wyvern, find out what happened to Ragnar and find a way to drive the Throg off planet and save both himself and Ragnar, as well as the Wyvern. This being a Norton novel, he of course succeeds.

What I liked here was that Shann had his own backstory, of having lived in the slums of another planet and through his own efforts and hard work managing to get a place in the Survey corps. This backstory is mostly hinted at, explained in a few sentences here and there but would be enough to fill another novel. It shows off the width and depth of Norton’s universe, each novel only showing a snapshot of it. Unlike many other writers of the same vintage, you never get the feeling that her planets are just stage settings. They have histories that continue once the story is done.