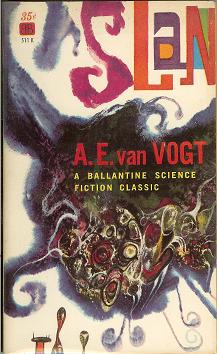

Slan

A. E. van Vogt

159 pages

published in 1940

“His mother’s hand felt cold, clutching his. Her fear as they walked hurriedly along the street was a quiet, swift pulsation that throbbed from her mind to his. A hundred other thoughts beat against his mind, from the crowds that swarmed by on either side, and from inside the buildings they passed. But only his mother’s thought were clear and coherent–and afraid.”

The opening sentences of Slan show why A. E. van Vogt was the most popular writer of science fiction’s Golden Age, somebody who in 1940 could not only be compared to an Asimov or Heinlein, but compared favourably. Van Vogt had honed his craft on writing “true confession” stories for the pulp market, then got into science fiction with a big bang in John Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction with “Black Destroyer” — the story that would decades later inspire the Alien movie. For about a decade or so he was incredibly prolific, inventive and with an almost instinctive understanding of how to push his readers’ buttons, learned while writing sob stories for the romance pulps. All these qualities come together in Slan and if you want to understand van Vogt’s appeal, this is the best novel to try: short, focused and tense.

Slan is the story of Jommy Cross, a mutant, a slan, like all slans stronger and smarter than ordinary humans and equipped with two golden tendrils on his forehead which gives him the ability to read minds — but he’s only nine years old. And he and his mother are caught in the very centre of Centropolis, she sacrifising her own life to enable him to escape from the slan hunters, the secret police that shoots slans on sight, because slans are too dangerous to be allowed to life. Those slans who haven’t been murdered yet have to live in secret, hiding their abilities and their tendrils. Jommy does not know how many of them are still or if he’s the only one, but he knows that he is their last hope, that he has to survive to one day take on the might of the dictator of Earth, Kier Gray, as well as the chief of the secret police, the head slan hunter, John Petty. And then there’s the captive slan girl, Kathleen Layton, subject of a power struggle between the two men…

Kier Gray, though a dictator and hunter of slans is through the point of view of Kathleen revealed to be a noble man, fighting for a place for normal humans in a world in which the hidden superscientists of the slans are decades ahead in their research and mastery of science, locked in struggle with those like John Perry who are just out for their own power and glory. Jommy Cross meanwhile, who is the heir to much of the slan superscience, his father having been one of the most brilliant of the slan scientists, discovers that there are other slans, slans without the golden tendrils that give them telepathy, but who can shield their thoughts to him and who have been secretly manipulating humans and slans both…

There are more twists and revelations van Vogt adds in only 159 pages he has for his story; it’s a bit of an understatement to calll this a plot driven story. Characterisation is broad, making use of pulp shorthand, the prose is short, to the point but effective. What Slan really got going for itself are the ideas. It’s not the first novel about mutants — Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John was published five years earlier — but it’s the one that popularised and shaped the idea of a race of mutants superior to humanity in abilities and skills, hated and feared by normal people and having to hide their otherness. Everything The X-Men is about was first present in Slan.

And it has a huge impact on fandom in the 1940ties, with some fans taking it so seriously they set up fan houses called “slan shacks” and started trying to breed the coming race. The idea of a superior race evolving out of humanity of course fit in quite well with the general atmosphere of the times, what with all the ideas about eugenics and other much later discredited unpleasantness doing the rounds back then. The idea of directed improvement of the human stock was generally accepted and Slan spoke to science fiction readers, who more than most not just accepted but welcomed this idea. In fact, quite a few fans already suspected they themselves were to be the new super race, hence that whole “fans are slans!” idea. Sadly the truth is otherwise.

Looking back at Slan some seven decades later its appeal is much diminished, its revolutionary impact not quite understandable anymore. There have been newer and better novels about mutants and superhumans, while science fiction on the whole no longer believes in telepathy or mindreading and psionic powers and finds it all a bit embarassing even. Van Vogt himself is barely read, his reputation demolished both by his critics (e.g. Damon Knight’s devastating portrayal of van Vogt as a dwarf using a giant’s typewriter) and his own later work, rewriting and fixing up his old stories into “new” novels. His ideas, both for plot and for how to write his novels, would become increasingly outlandish while he lost his ability to focus his writing, making his work increasingly incoherent. Yet for a while he was perhaps the most popular and important sf writer in the world, and Slan his best novel.