Golden Witchbreed

Mary Gentle

460 pages

published in 1983

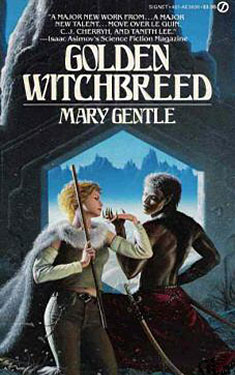

It was the beautiful Rowena cover that got my attention, a long long time ago when I was browsing the English shelves at my hometown’s library. Showing a blonde woman in jeans and fur cape, armed with a stave and linking fingers with an obviously alien six fingered man, two swords at his side. That intriqued me, it promised both adventure and romance and it got me to pick up the book and that was how I got to know Mary Gentle. I’m not sure how old I was, but I must’ve been no older than sixteen-seventeen and Golden Witchbreed was arguably the best novel of hers I could’ve started with, much more easier to get into than most of her novels would turn out to be. But though I loved it when I read it and remember it fondly, I haven’t read it since. Which was why I put it on the list for my Year of Reading Women project. I wanted to know if the book I remember was still as good as I remember.

Golden Witchbreed I remembered as a planetary romance, emphasis on romance. It starts with the cover with the two lovers holding hands. The woman on the left Lynne de Lisle Christie, envoy from Earth to the primitive, medievaloid world of Orthe, there to represent both Earth to the Ortheans and to judge Orthe on its fitness to trade and partner with. The Orthean she holds hands with therefore should be her alien lover, Falkyr. I remembered their romance as central to the plot, the circumstances in which it took place ultimately forcing Christie to go on the run and having to travel through most of the civilised lands of Orthe. Apart from that recollections were hazy.

And unfortunately, the part I did remember, though true in outline as far as it goes, was completely wrong. There was a romance between Christie and Falkyr, following the Orthean custom of becoming arykei, but it’s nowhere near as important as I thought it was. It happened relatively early in the book and at a crucial point in the plot, but that’s it. Instead Christie gets caught up in intra-Orthean politics, with the existence of otherworlders an intensely political question, with some not believing in them even when confronted with the evidence first hand, some wary of any contact with Earth, others looking for the potential in such trade. The romance is just a side issue, soon left behind; the real love story is between Christie and Orthe.

As such, on the surface at least it is a true planetary romance, eager to showcase and explore the world Mary Gentle has thought up, hitting all the highlights on the map in the back. What sets it apart from most other such explorations, both science fiction and fantasy, is the depth of the world Gentle has created. This is more than just a stage for the heroine to trek over. As such it reminded me both of Nicola Griffith’s Ammonite and C. J. Cherryh’s Foreigner. With the Cherryh it shares the confusion of alien political intrigue, with the Griffith its sense of a fully realised world in which gender is radically different from Earth norms.

On Orthe like Earth there are two genders, male and female, but Orthean children are ungendered until puberty, when they go through a crisis and emerge male or female. Gender and gender roles therefore are nowhere near as ingrained as on Earth, with a lot of female characters in roles traditionally male. Gentle makes no fuzz about this, never explicitely setting out this connection as I stated it here. As is the case with all her stories, the reader has to pay attention and figure things out for themselves. As a small example, in a throwaway scene one important male character casually mentions having been arykei with another named male character. Blink and you’ll miss it.

Next to the gender, the political systems of Orthe are what sets Gentle’s creation apart. For what seems to be a medievaloid planet, Orthean society is relatively egalitarian, though of course nowhere near democratic. There is a supreme ruler, but they are elected every several years, there is a court, but the heart of Orthean civilisation is the telestre, a combination commute, family and estate; ideally every Orthean belongs to a telestre, as does all the land, though that is held in common — when Christie in an early conversation says she’s no landowner, her Orthean friend responds with shock to the very idea of owning land. Together the telestres form the Hundred Thousand, the Southlands, Orthe’s main civilisation/country.

Then there are the Golden Witchbreed of the title, whose empire was overthrown five thousand years ago, in which collapse the telestre system evolved. Throughout there are hints that the witchbreed had a much higher level of technology than Orthe now has, making the Southlands not so much a pre-industrial as a post-collapse society. In her journeys around Orthe Christie ultimately also comes to the one place where she could learn the truth of these claims. The central scene in which these revelations are unfolded is one I’ve seen dozens of times in books, movies and comics, the only time I found Gentle to be a bit pedestrian.

Golden Witchbreed was not quite the book I remembered, but it was the better for it. I’d still argue that for people new to Mary Gentle’s writing, this is the best, most conventional novel to start with. There are already hints of her more opaque writing style in here and it’s a good way to ease into it.